The soul is a castle, according to 16th century Spanish mystic Teresa of Avila, in which God Herself dwells. At the center of this castle God gleams like a diamond. In Teresa’s classic work The Interior Castle, the soul’s castle holds seven different dwelling places on the way to love’s radiant center, seven deeper stages of prayer that finally lead to the place where God and the soul meet in undivided intimacy.

But castles are cavernous, and searching for treasure is often precarious. There are dark corners in castles, twists and turns, secret passageways and multiple rooms in which we lose our way. And that’s for those of us who make it into the castle in the first place. Many of us, Teresa says, remain in the outer courtyard, on the surface or the exterior of life, and we’re unable to access our inner lives and thus unable to abide in God.

Jesus in John’s gospel talks about the soul’s dwelling places, too: he tells us that in his Father’s house there are “many dwelling places.” (John 14:2) While interpreters of this passage have often pictured John’s dwelling places as heavenly hotel suites for the afterlife, spiritually astute readers of John’s gospel know that this Father’s house is available to spiritual seekers now. The Father’s house is that kin-dom of God realm in which we participate here, in this reality, and then also in whatever worlds are to come.

Teresa writes her book because a Catholic superior tells her too. The first paragraph is her complaining about it: she’s already written the content in other works, she says; she has been ill and lacks the desire, she says. At this point in her life Teresa is a famous and politically well-connected woman, and yet her status itself is upheld by her obedience to the hierarchy. In a time in which women’s vocational choices are generally limited between child-bearer and nun, Teresa chooses nun.

Women in these days are not allowed to read Scripture aloud, much less write books, preach sermons, and teach men how to pray (all of which, by the way, Teresa ends up doing). Muslim women who convert to Christianity in Inquisition Spain face possible banishment for wearing headscarves, but Christian women risk punishment for scarves, too, for fear they are engaging in illicit sexual activity. And for the women who do sleep with men other than their husbands, well, a law permits the husbands to publicly execute their wives and their lovers.

It’s no wonder, then, that Teresa peppers her writings with excessive examples of self-flagellation, reproach, and over-emphasization of her loyalty to the Catholic Church. One of the ironies about this time period is that monastic life creates a pocket of freedom for women to exercise agency and leadership. In this context, Teresa manages to become the founder of a new, reformed order, the Discalced or “barefoot” Carmelites. These are monks and nuns living out a simple, more stripped down version of Christian life, as opposed to the “well heeled” or Calced Carmelites. They are a little too comfortable in their convent suites, Teresa thinks, and John of the Cross, too, and indeed, monasteries wield much of the wealth and power in their day.

The doorway into the castle is prayer. Teresa’s doorway is connected to Jesus’s rules for entry, too: “Believe in God; believe also in me.” This is the way into the dwelling places. On first glance, this verse of John’s appears to be yet another doctrinal spear to bludgeon nonbelievers. And certainly, Christians have turned John 14:6, “I am the Way, the Truth, the Life” into a clobber text arrogantly to declare the wrongheadedness of other religions. But belief in John’s gospel is not about hard and fast exclusionary lines. Belief in John’s gospel is about trust; it is a posture of relationship, the willingness to say “Yes” to the divine. And we cannot pray, or communicate, or—that longstanding Johannine theme—abide in God, unless we first trust. It’s trust and prayer that bring us into the inner realms of the castle, the Father’s house, which is the divine depth of our own lives.

There’s a long accumulated history, however, of Christians failing to be about the thing that Christians are ostensibly about. There is not a lot of room for soul in Teresa of Avila’s 16th century Spain. These are the days of religious renewal movements, such as the Jesuits; this is the day of the Council of Trent and a Catholic renewal, in addition to Protestant Reformation, days of mystical awakening, such as with Teresa and John of the Cross; and yet these are days of Catholic repression and reaction.

In Spain, the 16th century brings days of the Spanish Inquisition. Isabel and Ferdinand have forced Jews to convert to Christianity or be expelled from the country. Thousands choose to convert rather than flee, including Teresa’s own grandfather Juan. He becomes a converso, a convert, and decades before Teresa is born, he is forced to walk a walk of shame through his town of Toledo with other converts and their families. Teresa’s father Alfonso is likely there. Much like Hester Prynne’s “A” in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter, the Catholics compel Teresa’s grandfather Juan to wear a robe, a penitential garment for the occasion called a sambenito, which bears a cross and flame on the back. For the rest of his life, Juan climbs the ladder of social hierarchy and never looks back, carrying his Jewish heritage as a hidden and dangerous secret.

Of course in John’s day, people do not wish to hear about the soul, or the kin-dom of God, any more than they do now. Jesus, after all, is about to be put to death at the hands of the religious and political authorities. His most dangerous act is not overthrowing an imperial system, but rather claiming that “I and the Father are one.” Criticizing a religious system and insisting on the immediacy of divine experience is never popular, because then you are demonstrating that you don’t need the church anymore. You may choose loyalty to the church still, finding joy, community and fulfillment through the church, as Teresa does, but you do not depend on it in the way that you used to.

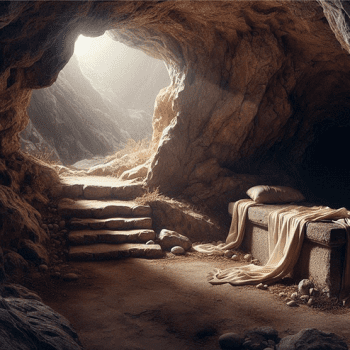

Much of what Jesus is up to in John is simply insisting that “Yes,” there is room in this world for the soul. In my Father’s house are many dwelling places. Jesus stands in the Jerusalem Temple, earlier in John, and says, “Destroy this temple, and I will rebuild it in three days.” (John 2:19). In other words, “I AM the temple, I am the castle in which God makes her home.” Or, likewise earlier in John, Jesus ends disputes about whether Jews or Samaritan temples are the proper place to worship, whether Congregationalists or Catholics have a corner on the market: “the hour is coming, and is now here, when true worshippers will worship the Father in Spirit and truth.” The Father’s house, the Mother’s house, is nothing less than the kin-dom of God within which, while infinitely more expansive than us, nevertheless kisses us in our innermost realm, the soul.

It is up to us to enter in.

Photo by Stefan Kunze on Unsplash