(Druid Reflections on the UU Experience, Part 2)

“Never underestimate the value of a convenient meeting place…” This post is part of a series in which I explore the many different spaces and places of spiritual community within Unitarian Universalism, and how UUs, Pagans and UU-Pagans can cultivate these shared spaces together.

I have a certain unshakable ambivalence about this whole idea of being “progressive.”

That might come as a surprise, considering I’ve already confessed that the progressive values of Unitarian Universalism were what first inspired me to explore this religious community, and they continue to speak to me in powerful ways.

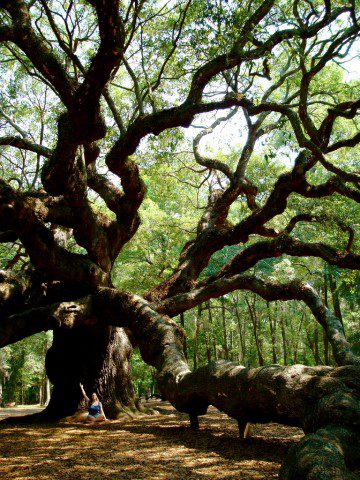

My ambivalence stems, at least in part, from my bone-deep commitment to nature worship and ancestor wisdom as important aspects of my spiritual life. In a culture quite enamored with its own progress, I think we can sometimes be too quick to rush on ahead to the next promising solution shining on the horizon, too quick to forget the lessons of history and, more importantly, the lessons of a living earth so much more ancient than we can possibly imagine. Though I would probably be first in line for the “progressive” label if we were being rounded up and categorized, it’s difficult to think of my Druidry as progressive when so often it feels instead like digging in my heels, sinking my fingers into the dark, solid earth and holding on for dear life. My commitment to social and environmental justice, to the sacredness of memory, love, service and beauty — these feel less like “progressive” ideals and more like anchors that keep me grounded. They are sturdy stone outcroppings to which I cling against the relentless pull of a raging river, giving me a sense of gravity in a rushed and reckless mainstream that sometimes seems intent on plunging headlong off a cliff. To me, these are not values that make me “progressive.” They’re simply what it means to be a Pagan.

Yet it’s also true that these same values are what give me a sense of direction in my life, and challenge me to grow as a person as I strive to uphold them and live up to their inspiring vision. They are the same values encapsulated in the Seven Principles of Unitarian Universalism, which I hold in common with many UUs, Pagan and otherwise (as well as many non-UUs for that matter). Such values can empower us, giving us something to work towards. They can act as a center of gravity that draws us forwards into a better way of living in community with one another.

One thing that is not explicitly listed as a UU Principle, however, is ambivalence — though from what I’ve seen of our quirky community so far, it probably should be. For me, sacred ambivalence, the holiness of liminality, is a principle that pulls me into its orbit again and again. I can’t escape the drag of uncertainty, the uneasy knowledge that whole-hearted, uncritical commitment to even the most well-intentioned values can sometimes lead us astray.

I’m reminded of this fact especially whenever I’m confronted by lingering unconscious assumptions shaped by the Judeo-Christian worldview which gave birth to UU, and which show up sometimes in the most unexpected places. While the Seventh Principle encourages UUs to respect the interdependent web of all existence and to value the diversity of that web — a beautifully polytheistic attitude, you might think, which should warm the cockles of any Pagan’s heart — in some ways this diversity is still often framed as just so much quantum foam floating on the surface of a vast unifying silence that transcends and subsumes all things. Call it God, or Spirit, or Mystery, or whatever you like. Scratch a Universalist, and usually you’ll find they bleed just like a monotheist.

This ultimate nameless and silent Spirit was the topic of much conversation, for instance, in a small poetry discussion group that I participated in at my local UU church last year. As the only polytheist in the group, I found myself uncomfortable with my own frustration at the reading selection, Sonata for Voice and Silence: Meditations, by UU minister Rev. Mark Belletini. Try as I might, I just couldn’t get over how Christian it all felt, even when it was obvious how hard Belletini was working to reinvent Christian theology and translate it into something more universal. Take his poem, “Creation Story” — a retelling of the Christian eschatological narrative that begins in Genesis and carries through to the ultimate salvation of the New Testament. In his poem, Belletini depicts the whole history of the universe as a singular process (playing with the imagery of condensation), which leads first to the creation of stars and planets, then to the human mind, then to the fallen state of human violence and isolation, and finally to the salvific realization of love and the “small, small jewel of silence, / that sums the whole evolution of creation / with the elegance and honesty of wordlessness.”

“This guy is so preoccupied with silence, it’s a wonder he even bothered to write a book about it!” I commented to my husband after reading this poem which, like almost every poem in the book, ends with a call to silence. (Never mind that the scientifically-literate part of me balks whenever someone refers to evolution as if it were teleological.)

This conception of God as a silence that transcends all human attempts to describe it is a common one within Christianity, particularly in contemplative and apophatic approaches. In his book, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality, Belden C. Lane explains how this approach to a transcendent monotheistic deity arose early in Christian thought as “a prophetic critique of theological presumption”:

It insisted that any similarity one might find between the Creator and some aspect of creation could not be expressed without acknowledging a still greater dissimilarity. […] As a mode of speaking about God, the apophatic tradition guarded the boundaries of the theological enterprise, emphasizing the ineffable and incomprehensible character of the divine. As a mode of contemplative ascent to God, it taught spiritual poverty and the imitation of Christ’s self-emptying love.

For centuries, the search for a God that is utterly transcendent and wholly other has inspired spiritual seekers to head out into the wilderness. The silence of the mountain peak, the emptiness of the desert, and the darkness of the cloud of unknowing, have all been recurring images of Mystery at the heart of a contemplative Christian life.

The concept of transcendence naturally lends itself to a progressive worldview. Lane notes that postmodern thought can itself be seen as a recovery of the apophatic tradition. “Much of Western culture, in philosophy and the arts,” he writes, “has been preoccupied with the inability of language to do all that we once expected it to do.” Our labels and categories fail us. Our narratives and metanarratives are always flawed and ultimately unsatisfying, broken open by all those who refuse to be restricted by old, worn-out definitions of right and wrong. We have no choice but to recognize the undeniable diversity of stories that surround us, each with their own perspectives and biases. Lane writes, “The recovery of the apophatic tradition at the end of the twentieth century is part of a much larger distrust of words in our culture. It is an effort to quell the verbiage that limits genuine discussion of what is most important.” Surely, we plead, there must be something that can unite us! If it cannot be our words, what else can it be but our silence?

How often have I heard it said among religious progressives that we are all working our way up the mountain towards the same goal, even if we’re taking different paths to get there. Whether it’s the empty silence of the desert or the peak of the mountain, this holy Thing-Whatever-It-Is that we’re all striving for is conceived of as the same: a basic underlying unity, a singularity, a oneness — a unitarian universalism, if you will. What goes without saying is the assumption that, once we reach it, not only will we all agree on what it is, but we’ll all be in agreement with each other about pretty much everything else as well. Our lives are anything but silent, and yet by seeking the silence that lies beneath it all, we hope to realize the promise of the silence-to-come as an experience of wholeness, a wholeness within which all the chaotic noisy parts are quieted once and for all.

But I cannot believe in this kind of silence, I don’t think it exists. I look for that silence, and like the monotheistic God of Christian tradition, I continually fail to find it. I was raised, like many people in Western culture, to think of divine Mystery as the mystery of union — whether that union is with God, or simply with the universe and one another. But what I have found instead, time and again in my spiritual seeking, is the Mystery of the Many: a thrumming, churning multitude that refuses to be simplified, neither reduced “downward” into atomistic materialism nor reduced “upward” into an ultimately transcendent monism.

I have been to the desert, and it is not empty. Even in the absence of other humans — perhaps especially in their absence — the desert comes alive with even the slightest fall of rain, and its diversity is revealed. At dusk, the weird and wondrous creatures hidden beneath the sands all day to escape the heat of the relentless sun finally come out to explore. I have been to a handful of mountaintops, and every time their height only serves to reveal sweeping vistas of landscape unfolding around me in all directions: valleys and forests lush with variety, oceans murmuring in an always-shifting soup of life in which dwell the largest living things on earth as well as the microscopic organisms on which they feed. Even in the depths of winter, the darkness does not have its final say, but snowfall illuminates the shadows with reflected starlight.

In the same way, my lived experience of progressive values leads me to the conclusion that it is not a unity of agreement that we are seeking, but the freedom to disagree in a multitude of astounding and beautiful ways, each seeking our own paths. Some paths lead to the mountain peak, but others are perfectly content to wander among the foothills. Some dwell in the intimate harshness of the desert, while others strive to cross it and reach the sea. Each path is its own reward, each reveals its own experience of the landscape. And each path opens up myriad unique relationships and realizations that cannot be discovered or lived in any other way. The more we embrace diversity as a guiding value, the more obvious it becomes that diversity, multiplicity, is a good in itself, to be valued for its own sake and not simply for the imagined unity that it might one day promise.

The principles of love, service, beauty, responsibility: how fantastic it is to discover there are a million ways to embody these values in our lives! What a blessing that each of us will strive towards these goals in our own unique ways!

Yet within the din of our many ways of loving, there is still a need for silence, for a quiet space in which to catch our breath. I would not betray my fellow introverts by denying how vital silence and solitude can be for the soul. And so I find myself drawn back again — by the tricky pull of sacred ambivalence — toward a need to celebrate values that are so often overlooked, especially by a church culture defined by its extroverts. Never underestimate the value of a convenient meeting place, even if the meeting is just a small discussion group in which a handful of people gather to share and explore… It’s easy to think of these meetings as a waste of time unless they consistently draw a crowd, but there is a deep need for more intimate ways of being and belonging together. Week to week, those who are able to attend these small group discussions undeniably influence the shape that the conversation takes. In the space opened up within a small group, each person’s individuality and unique personality has a chance to shine, fully seen and recognized by others. Respecting diversity is not a numbers game, but a matter of perspective.

In fact, it was just such a shift in perspective that brought me to a new appreciation of Belletini’s poetry when, during our small group discussion, our own minister (the ever-insightful Rev. Kate Landis) pointed out that he’d written this particular collection of poems as preludes leading into the “moment of silence” during the worship service.

Now, I’m a big fan of the moment of silence (though I’m aware that not all UU congregations incorporate them into their worship). I think a few moments of quiet meditation offer a refreshing and necessary break from the format more typical of Protestant Christian services that mostly involve sitting still listening to an authority figure lecture at you between organ-accompanied hymns in a range that nobody can comfortably reach. As a break from this sort of ritual, silence comes as an opportunity for gentle embodiment. It helps to balance out the heady intellectualism of Unitarian Universalism and the tendency of its Christian heritage towards disembodied theological abstraction. To sit quietly with your own body for a moment or two, surrounded by the quietly-breathing bodies of many others, is a grounding experience. Within these moments, we have time to discover that silence is not a blank emptiness, but a chance to listen more deeply, with greater attention. What we hear might be only the sound of our own breathing, the ringing of blood in our ears, or the tension in our own limbs… or we may hear the restless shuffling of other feet, the shifting weight of our neighbor seeking their own center of balance, or the occasional cough of the person sitting next to us. As Garret Keizer says, “To say that you want to live in a less noisy world, and to say it with any depth of conviction, is in essence to say that you’d like to have your body back.” Here in the silence of the body, we discover yet again that silence is not really silent at all.

In the same way that silence offers us a change in perspective in the midst of word-heavy worship, so too do the progressive values of UU provide a necessary balance to what can become a certain regressive attitude in modern Paganism: the tendency to value the past uncritically, the attempt to imitate the ways of our ancestors for the sake of imitation itself, rather than seeking our own path in the present moment. As much as I strive to honor my ancestors and stay grounded in the wisdom offered by earth-rooted tradition, I also grow weary of this mistake that seems all too common among Pagans today. For it is a mistake to believe too strongly in the power of cultus and habitus, to believe that if we can just recreate the correct ritual formulas in just the right way, that alone will be enough for us to capture the spirit that once inspired them. There is no shorter path to the empty formalism of the cargo cult.

So it is the dance of sacred ambivalence that moves me through the ebb and flow of my spiritual life. There is no dance without the tension of opposites, pushing and pulling against one another. In the end, even the desert monks and mountain sages recognized the need to temper the apophatic love of silence with the kataphatic enthusiasm for language, metaphor and imagery. Lane understands this when he writes: “Kataphatic expression without the critique of apophatic prophecy becomes dogmatic, abusive, overly confident in its powers of utterance. Similarly, apophatic criticism, in its rejection of language, its challenge of every conclusion, leads, without a kataphatic willingness to commit itself, to an empty nihilism, never affirming anything.”

He concludes:

[T]hese two ways of describing the mystery of God — the way of darkness and the way of light, the ambiguity of silence and the transparency of articulation — can never be separated. There is danger in posing a sharp dichotomy between apophatic and kataphatic approaches, as if the one were superior to the other, as if the higher and purer silence of apophatic mysticism properly took precedence over the concrete concerns of community and speech. These two ways of delineating the image of God must by mutually interconnecting. They require each other.

If “Creation Story” still drives me up a wall (albeit a small one, like one you might find hedging a rambling country path and barely succeeding in keeping the cows in), Belletini’s poem “Praisesong” is perhaps one of my favorites for expressing this mutual relationship between speech and silence, between kataphatic and apophatic spirituality. In it, Belletini shows us beautifully how contemplating the nameless bubbles up into a joyful cacophony of names, and how the astonishment we feel in the face of the multitude leads us back once more into profound silence:

O Mystery that everything exists!

I cannot name you!

…

Yet, nevertheless, even though you are nameless,

I am brimming with names

like a pitcher overflowing

with refreshing water.