The Gospel According to St. Luke: A Book Report

Last time, we discussed the scholarly background of Luke, and why I personally find the academic consensus significantly less convincing than the traditional view. Yet I’m sure that the whole time you were waiting anxiously, wanting to interrupt me (save that modesty forbids) to insist, “Yes, but never mind all that! What are Luke’s THEMES?” Don’t worry, I got you.

To begin with, Luke is the third and last of the Synoptics—the Gospels that are substantially similar outside the Passion narratives. That said, Luke differs a little more from Matthew and Mark than they do from each other. About a fifth of the Gospel of Matthew is unique to Matthew, and of Mark’s, only about 3% of the material is unique. By contrast, a whopping third of Luke is present only in his account. He is widely known (thanks not least to the Charlie Brown Christmas Special) to offer the most extensive account of the Nativity, and the only canonical description—get out of here, “Gospel of James,” and take your weirdo friends with you—of anything between Jesus’ infancy and his baptism1; the only detail he leaves out (oddly, since it seems to suit his purpose pretty well2) is the Epiphany and its aftermath.

A tetramorph based on Revelation 4:6-8; the

faces are traditionally seen as the Evangelists.

The prevailing equivalences are: man—

Matthew; lion—Mark; ox—Luke; eagle—John.

At the other end of the narrative, Luke also contains as much post-Resurrection material as John—that is, about twice as much as Matthew and five times as much as canonical Mark, which doesn’t even include a direct Resurrection appearance (though the composer of the “Longer Ending” of Mark was apparently familiar with Luke and tried to harmonize the two); and, while Matthew and John both hint at it, Luke alone contains a direct account of the Ascension, or rather two such accounts if we differentiate between Luke 24 and Acts 1.

The rest of Luke’s unique material varies; some of it consists in miracles (like the raising of the widow’s son at Nain), some of it in memorable encounters (like that with Zacchæus). One detail of the Passion narrative, Jesus’ examination before Herod, is known to us only from Luke. And the Third Gospel alone contains eleven of Jesus’ parables. This includes several of his most widely beloved ones:

- the Two Debtors

- the Good Samaritan

- the Insistent Friend

- the Rich Fool

- the Barren Fig-tree

- the Lost Drachma

- the Prodigal Son (analyzed here in three consecutive posts)

- the Shrewd Steward

- the Rich Man and Lazarus

- the Judge and the Widow

- the Pharisee and Tax Collector

This list is disputable is certain details. A twelfth uniquely Lucan parable is sometimes identified, the Parable of the Great Feast, and the setting and point being made do seem somewhat distinct in Luke, but there is a direct parallel in Matthew, so I have omitted it here. The Parable of the Two Debtors is clearly similar to the setup of the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant, but I judged the contexts and contents to be different enough to merit their filing under separate heads. That of the Barren Fig-tree also obviously resonates with the episode of the blasting of the fig tree during Holy Week, related by Matthew and Mark, but there we have the difference between a parable and a miracle.

What Luke Cares About

Many of these parables indicate, sometimes by title alone, something of Luke’s particular focus. That focus can be summed up in one word: the disadvantaged. Luke, and Acts after it, displays a persistent interest in the well-being and fair treatment of those who were considered second-class citizens—by the Judaic clerical class for being Samaritans or Gentiles, or by the bulk of respectable society for being poor, or by all of society for being women. Each of these interests merits a little more discussion here.

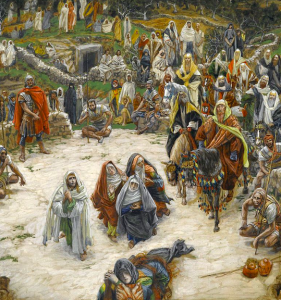

What Our Lord Saw From the Cross (ca. 1890),

by James Tissot.3

1. The Ethnic Interest

The book of Acts continues to carry Luke’s interest in inter-ethnic reconciliation forward, and its contours are easier to highlight in Acts. In its first chapter, the Great Commission is given: “ye shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judæa and Samaria, and to the uttermost part of the earth.” This sets the stage. Next, in the second chapter, the anti-Babel of Pentecost appears, and St. Peter adumbrates the opening of the Church to the Gentiles: “For the promise is unto you, and to your children, and to all that are afar off, even as many as the Lord our God shall call.” In chapter 8, when the Church is scattered by the lynching of St. Stephen, we see Samaria evangelized. In chapter 10, the inauguration of the Gentile mission takes place, originally under Peter’s own auspices. Chapter 16 shows us the transition from Asia to Europe (already conceived by geographers at the time as separate continents), and in the last chapter of the book the symbolic culmination of the Great Commission is reached—”we came to Rome.”

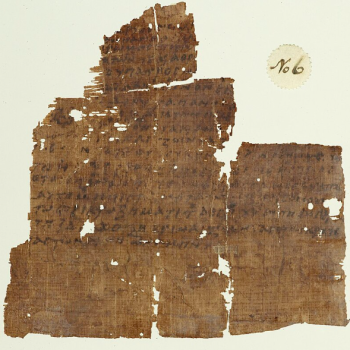

And it is in Acts 6:1-6 that we learn that the office of the diaconate was first created in response to ethnic tensions in the infant Church. I come to this out of order, because it includes a striking decision taken by the Church for the first deacons. This decision is not openly stated. It is only hinted at, in the fact that all seven of them have Greek names rather than Hebrew or Aramaic ones (and one, Nicolaus of Antioch, is noted to have been a גֵּר [gêr], a Gentile convert to Judaism). The Greek names are surprising because, this being Palestine, most Jews spoke Aramaic as their mother-tongue rather than Greek; however, there were a handful of “Hellenists” whose first language was Greek, both in the Holy Land itself and in the adjacent regions of Egypt and Syria.

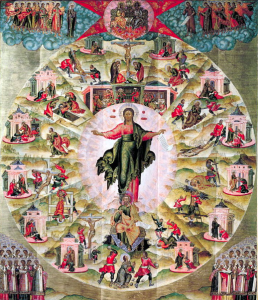

The Ministry of the Apostles (1660), an ikon

written by Fyodor Zubov.

In other words, the book of Acts tells us that when there was complaint of inter-ethnic discrimination in the distribution of charitable resources, the community promptly elected seven members of the ethnic minority and asked them to handle the complaint. If we’re going to talk about our faith influencing our politics, “the primitive Church in Jerusalem did an affirmative action” is something we should, to put it mildly, grapple with.

Returning to the Gospel, this interest in ethnic reconciliation is perhaps less pronounced, but it is already noticeably present. For example, as mentioned, only Luke includes the Parable of the Good Samaritan, while on the other hand he leaves out the easily-misinterpreted episode of the Syro–Phoenician woman. Similarly, in his version of the Mission of the Twelve, Luke omits the instruction to restrict themselves to Jews proper (i.e., not even Samaritans), and he does not add it in the Mission of the Seventy—which, in fact, immediately precedes the Parable of the Good Samaritan! It is also in Luke alone that we find St. Simeon’s prophecy (now used in the Church’s daily prayer as the Nunc Dimittis), including the line, which could practically be lifted directly out of Second Isaiah,4 identifying the Holy Child as “a light to lighten the Gentiles”.

2. The Class Interest

The Parable of the Rich Fool (1627),

by Rembrandt van Rijn. Note how his hand,

holding a coin, obscures the light; meanwhile

his books seem ready to collapse and bury him.

At the inception of the Gentile mission (Acts 10:1-4, echoing Tobit 12:8-9), both the narrator and the angel who appears to Cornelius attribute his special favor with God to his almsgiving. This resonates with the Pauline epistles; they make frequent references to care for the poor, more so than the “Catholic Epistles” (Hebrews through Jude), which do not omit the topic of care for the poor, but—James aside!—don’t focus on it as persistently. As with the inter-ethnic issues, so here with the economic, things grow more explicit and emphatic in Acts: the small-c communism of the primitive Church is discussed, and St. Paul’s refusal to burden churches with supporting him is alluded to.

Here also the frightening cases of Ananias and Sapphira and of Simon Magus are related, all three of whom were cursed by St. Peter for financially-characterized sins. These appear to be the only cases in which the terrible power of retaining sins (cf. John 2:23) is exercised—unless the references in the Pastorals to Hymenæus, Philetus, and Alexander are instances of the same thing. And note that, when these three do come up, allusions are also made to things like “devouring widows’ livelihoods,” while Alexander—assuming it’s the same Alexander in I and II Timothy—is identified as a coppersmith, copper being one of the lesser precious metals and a frequent base for coinage.

Once again, we see the same themes already present in Luke. His account of the Beatitudes, for example, gives the “literalist” version of the first: His text simply says Blessed are the poor, contrasted not long thereafter with a Woe to you who are rich. Or look at the eleven parables peculiar to Luke, listed above—nine of them feature money as an important influence on either the moral character or the decisions of the parable’s protagonist. (The Barren Fig-tree and the Insistent Friend are the only exceptions.) Still, the author shows himself anything but simplistic; Luke is also the sole Gospel to relate the story of Zacchæus, the repentant and famously short tax-collector.

3. The Gender Interest

And finally: this is the Gospels that spends the largest proportion of its narrative on women. Above all, it is the canonical Gospel with the most substantive infancy narrative, taking up the entirety of the first two chapters (and Luke has long chapters!), which discuss not only the Mother of God but the Baptist’s mother, St. Elizabeth.5 These first two chapters accordingly lead many Christians to think their ultimate source, at least in basic outline, was the Virgin herself.

The Three Maries at the Tomb (ca. 1470),

by Mikołaj Haberschrack, a painter from

the Kingdom of Poland.

I’ve occasionally seen the Magnificat urged against this, the idea being that a peasant girl could hardly have composed such a hymn. This is, first of all, as classist and sexist as “arguments” come; why on earth should a peasant girl be incapable of poetic talent?6 Second, it has a touch of question-begging to it, since we don’t have anything else that even professes to be by Maryam bat Yoakhim, and therefore can’t point to any stylistic inconsistencies with her “known corpus.” And third (and in my opinion, weightiest of all), the Magnificat consists more or less entirely in “stock” material—which, to be clear, is not a bad thing—and is closely modeled on the Song of Hannah from I Samuel 2. Is it really that hard to believe that a teenage girl from a largely oral culture, who had probably spent her whole life hearing texts from the Hebrew Bible each week at synagogue, would have difficulty composing a psalm that imitates earlier Biblical texts at every step?

Anyway, zooming back out to Luke! His interest in women’s status does not noticeably increase in Acts, though it doesn’t drop off; Luke even troubled to learn the name of the excitable servant-girl who kept the door at John Mark’s mother’s house: Rose, or Rhoda if you insist on not translating it. The Gospel has a still richer cast of women. Anna, a nun-like prophetess, appears alongside St. Simeon in chapter 2, and it is from Luke (beginning in chapter 10) that we get most of our picture of Martha and her sister Mary—only John also mentions them by name. (Considering the information he relates, I’m inclined to think there’s something in Dorothy Sayers’ idea that the family had been subjected “to much vulgar curiosity and political embarrassment,”7 if not worse, and that perhaps Matthew and Mark omitted them entirely, and Luke omitted the most sensitive final part of their narrative, to spare them further scrutiny.)

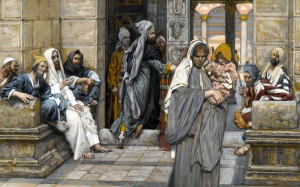

Le Denier de la Veuve [“The Widow’s Penny”]

(ca. 1890-1900), by James Tissot.

It is also Luke who makes a point of explaining, at the beginning of chapter 8, that at least part of the “bankrolling” of Jesus’ ministry with the Twelve was done by women, Martha seemingly among them. Three more are specified by name: Mary Magdalene; Joanna, the wife of Herod Agrippa I’s household manager, Chuza; and a woman named Susanna—whom I wasn’t able to dig up much more information about, except that the Eastern Orthodox also list her as one of the myrrh-bearers.8

There is just one mystery more that I’d like to address before returning to direct translation and commentary. (It’s not the relationship of Luke to the lost Gospel of Marcion; I may come back to that in a sort of appendix to this introduction, depending on how annoyed I stay about that stupid, stupid project to reconstruct it.) It is the fact that Luke and Acts are, or appear to be, addressed to somebody in particular:

“Most Excellent Theophilus”

… it seemed good to me also, having followed up on everything precisely, from the top in succession, to write to you, Theofilos, Your Excellency …

Now, the first message I made about everything, Theofilos, which Jesus began to do and teach …

—Luke 1:3; Acts 1:1

Remains of the Herodian palace at

Cæsarea-by-the-Sea. Photo by Deror Avi, used

under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Who was this Theofilos, or Theophilus? The straightforward truth is, we don’t know. There are a few possibilities.

One theory is that it is not so much a name as a title. If Luke and Acts were from the first prepared as catechetical documents, those receiving catechesis might have been addressed as “Theofilos,” perhaps thanks to the name’s handy double-meaning.9 This seems to accord reasonably well with the idea that St. Luke (supposing him to be the author) was aiming to aid St. Paul’s work as a missionary. This theory is a safe and credible one. There are two others, or two versions of the same alternative, that are much juicier, though they may be difficult to align with what facts we possess.

A Gospel for the Sadducees?

The office of high priest was under mixed Roman and Jewish control during the Herodian period (37 BC-70 CE, until the destruction of the Temple by the Flavians rendered the office moot). The actual effective reign of any member of the Herod family over any part of the southern Levant came and went; the high priest, however, was a constant: on the Jewish side, because he was essential to the function of the Temple; on the Roman, because he was treated as the ethnarch of the Jews. In consequence, rather than serving for life, high priests commonly served for a year or a very few years; the high-priesthood of יוֹסֵף בַּר קַיָּפָא [Yousêph bar Qaiyâphâ’], which lasted eighteen years (from 18 to 36 of the early first century), was rivaled in this period only by that of Simeon ben Boethus,10 who was King Herod the Great’s father-in-law during his tenure.

A ceramic replica of the high priest’s breast-

plate. Photo by Dr. Avishai Teicher, used

under a CC BY 2.5 license (source).11

It so happens that, of the twenty-five other men who served as high priests in this period, two bore the Greek name Theofilos. One was Theofilos bar Chanan (or Theophilus ben Ananus), who presided from 37 to 41; and Matithyahu bar Theofilos (or Mattathias ben Theophilus), who presided from 65 to 66, and was overthrown by the revolutionaries at the opening of the First Jewish War. The discrepancy between Luke and Acts here—”Theofilos, Your Excellency” versus just “Theofilos”—lines up with the idea that whoever this person was, they held an important official position in the empire when the first book was addressed to them, and no longer held that position when Acts was begun.

Is there any reason Luke and Acts could not have been addressed to one of them? I know of none. Some people might assume that no early Christian would have addressed himself to the templar establishment, but this is not the case—the Church regarded herself as primarily “in conversation” with mainstream Judaism well into the second century (as documents like St. Justin Martyr’s Dialogue With Trypho, written ca. 155-160 suggest). Moreover, if there is any truth to the idea that Luke had a conciliatory temperament—and I think that this particular deduction of modern scholars has merit—then I suspect trying to win over a high priest is just the sort of thing he would do. It’s also been pointed out that the early chapters of Luke are concerned with templar ritual: St. Zacharias making the incense offering, Jesus’ brith milah held punctiliously on the eighth day, the purification sacrifice brought by the Virgin and St. Joseph.

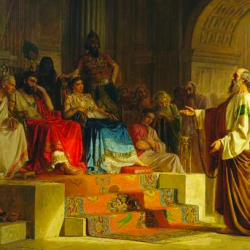

Still, it does not appear to be above critique of the priesthood, the group to whom the majority of the Sadducees belonged: mostly gentle, mostly indirect, but critique nevertheless. Many warnings against the Sadducees are omitted from Luke’s account, but the “seven brothers” puzzle put forward during Holy Week, which gives a case for the resurrection based solely on the Torah (the only Scripture the Sadducees accepted), is not. Moreover, as high priests and ethnarchs, both Theofiloi would have been remarkably wealthy men—and we’ve already discussed the discomfort Luke has to offer the wealthy. And when we come to Acts, we find Luke’s account of Paul’s trial before the Sanhedrin, featuring both the saint’s apology for insulting the high priest (despite the fact that the high priest—חֲנַנְיָה בִּן נָדְבְאָי [Chonanyah bên Nâdhvâ’y], Ananias ben Nedebeus—was in the wrong) and his assertion immediately thereafter that the real controversy over him was not about observing or failing to observe the Torah, but about “the hope and resurrection of the dead.”

Christ Before Caiaphas (ca. 1630-1640),

by Matthias Stom.

Of the two Theofiloi, the first (Theofilos bar Chanan) may seem like the obvious choice, since he was actually named Theofilos, rather than being a “son of.” However, this would place Luke exceedingly early, if that Gospel were addressed to him during his ethnarchate; 37-41 is just a very few years after the Crucifixion itself! If Luke’s mention of “many others” having written Gospels before him does refer to Matthew and Mark (or to anything, really), this would seem to be pretty implausible.

The Case for the Penultimate High Priest

Furthermore, while it may seem strange to us to address Matithyahu bar Theofilos as “Theofilos,” it wasn’t unknown to employ patronymics as a respectful form of speech. In fact, there’s another high priest whose patronymic has effectively replaced his personal name, someone we’ve already discussed here: Yousêph bar Qaiyâphâ’; “which, being interpreted,” is Joseph the son of Caiaphas, or Caiaphas for short. So it is credible that Luke could have been addressed to this penultimate high priest. Furthermore, his tenure as high priest was short: he was deposed by the rebels in 66, the year after he took office, on account of his Roman sympathies (another common trait among Sadducees). Addressing one volume to him with the honorific, followed by a second without it, aligns well enough with this high priest’s abrupt expulsion.

The account of the ending of Acts that I find most credible is that it concludes open-endedly because St. Paul’s trial had not concluded when it was written. It’s not wholly clear whether he had two trials or one; if he had one, and Luke was there in Rome with him, then Paul must have been in prison awaiting trial for a few years. This easily brings us up to the high priesthood of Matithyahu bar Theofilos/Mattathias ben Theophilus, which began in 65, the year after the Great Fire that ultimately led to the persecution of Christianity by Nero. It’s even possible that Luke, hearing of the brewing revolt in the Holy Land, composed his Gospel, rapidly followed by the book of Acts, in hopes of encouraging the high priest to convert and make last-ditch efforts to defuse the tension between the Judeans and the Romans, or, failing that, to align the collaborationist Sadducees with the pacifistic Nazarenes in hopes of making a joint effort to quell the violence before the Romans … well, took away “both our Place and our nation.”

The Destruction of the Temple (1867),

by Francesco Hayez.

However. This idea would require a very narrow time-scheme to work, so narrow as to cast some doubt on its credibility. The Great Fire happened in 64; we don’t know exactly how long it was between that and the criminalization of Christianity, but even if (as John A. T. Robinson suggests) there was a fairly substantial gap between the two events—I believe he suggests a year and a half, the fire in June of 64 and the criminalization in December of 65—it could hardly be long after that that St. Paul’s trial (or his second trial) did conclude, with his execution; for Nero committed suicide in June of 68. Three years or less to write the book of Acts is by no means unfeasible. But if Luke originally addressed his Gospel to this high priest, then he can’t have started it before 65, which already means both Luke and Acts need to be written in this three-year time frame. And, as long as we’re counting traditions as evidence, there is a tradition that SS. Peter and Paul were martyred on the same day, one year apart. This would more or less force their deaths to have occurred either in 66 and 67, or else in 65 and 66. Any earlier, and there’s nothing to execute Peter for: any later, there’s no Nero to execute Paul. So really, what we’re looking at is one year (the year 65) for Luke, and one (the year 66) for Acts—an Acts that, bizarrely, fails to mention the martyrdom of Peter.

All in all, then, I don’t think either version of the “Theofilos the high priest” theory holds enough water to adopt. Possible, but not probable. (Unless perhaps the later Theofilos held some other office that we don’t know about which would also merit the title “Your Excellency”—but if so, well, we don’t know about it!)

Footnotes

1Granted, the disappearance of Jesus in Jerusalem at age 12 is less “impressive” than the miraculous tales contained in, say, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas; but then again, it is arguably more credible and more appealing to think the Holy Child did not curse a playmate and cause him to die. I for one find that story a real vibe-ruiner.

2Many scholars conclude from this that Matthew’s account of the Epiphany, the flight to Egypt, and the massacre of the Holy Innocents (the bulk of Matthew 2) is historically false, and probably invented to give Jesus the “right” birthplace. I’m skeptical of this. For one thing, the only two documents we have (Matthew and Luke) that describe Jesus’ birth both agree in placing it in Bethlehem, and also agree that he did not grow up there—a strange lie to invent, and strange to imitate. For another, the “prophecy” that the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem, like many texts that the New Testament casts as prophecies, could have been explained away with the simple expedient of pointing out that, in context, it isn’t about the Messiah. If the facts were inconvenient, there were easier, neater ways to be rid of them than this. As for why Luke wouldn’t have mentioned the Magi’s visit when Matthew did, there are a few possible reasons. Over the early and middle first century, different parts of Judæa went back and forth between direct Roman governance and rule by client monarchs from the Herodian dynasty. If, say, Matthew were written in a place that was at the time under direct imperial control, then relating a nasty episode from the close of Herod the Great’s reign might not have been too risky. But if the Gospel of Luke were written while a Herodian were in power—perhaps during St. Paul’s imprisonment at Cæsarea-by-the-Sea (ca. 58-60, based on when Antonius Felix left office and was replaced by Porcius Festus), while Paul was daily hoping for a hearing from Felix, Festus, Agrippa II, anyone—it might be of great value not to offend the family! This might also explain why, though Luke does acknowledge the Baptist’s martyrdom, he does so exceedingly briefly, and without even hinting at the role of Herodias, unlike both Mark and Matthew.

3Though one might assume that figure directly clinging on the Cross is the Mother of God, her long, loose hair indicates that she is the Magdalene (correct or not, the belief that the “sinful woman” of Luke 7:36-50 was St. Mary Magdalene led to an artistic convention of depicting her with exceptionally long, voluminous hair). A little back from her, we find another woman, clothed in blue and white, with her hands upon her heart (cf. Luke 2:35); clearly this is Mary. The women behind her are presumably, as in Mark 15:40, “Mary the mother of James and Joses” and “Salome” (traditionally identified as the mother of SS. James and John, the bar-Zebedees, and occasionally called Mary Salome, to make things more confusing). The figure in green is of course St. John, the youngest of the Twelve and the only one not to desert Jesus in Gethsemane.

4I.e., Isaiah 40-55—chapters 56-66 are esteemed as Third Isaiah. Linguistic and theological differences between these sections of Isaiah move modern scholarship to interpret them as having different authors. We know from other passages, e.g. in II Kings 2, that the prophets sometimes formed schools or lineages—perhaps not unlike modern Hasidic dynasties?—and it’s possible that members of the school founded by Isaiah both preserved the contents of the first thirty-nine chapters, and subsequently added the remaining twenty-seven (rather than all of it being either Isaiah’s personal work or stuff falsely passed off as his).

5I gather that in calling Elizabeth the Virgin’s “cousin,” St. Luke was using the term broadly. It is not unheard of for first cousins to be around thirty years apart or more in age (as they must have been, if the Mother of God was of marriageable age when Elizabeth was sufficiently elderly to be past any natural hope of childbearing), but it is certainly not the norm; using the word “cousin” loosely, on the other hand, is a norm, and was until recently even in English (where we habitually drop the degree—first cousin, second, etc).

6Incidentally, this illustrates why bigotry is bad. Some people seem to think the objection to bigoted assumptions is that they’re Mean: The upshot of this is that people who like to think of themselves as Nice feel obliged to be unprejudiced, while people who like to think they “tell it like it is” find being accused of prejudice attractive. Now, the Lord out God has laid down clear instructions to love, and the most normal expressions of love are gentle and kind (to the vulnerable at least). Those Christians who not only behave otherwise, but do so deliberately and brag of it, openly defy their God; there is no amount of mocking “the Church of Nice” that can make this otherwise. However, in a conversation about bigotry, that’s actually beside the point. What’s wrong with bigotry is that—sticking to the example of poetry—it is, in reality, not relevant to a person’s poetic talent that they do or don’t have a certain amount of melanin in their skin, or a particular Y-chromosomal haplogroup, or certain primary and/or secondary sex characteristics, or the equivalent of a given income level. The idea that any of these things would be relevant is stupid.

7If memory serves, she made this suggestion in her essay collection Creed or Chaos?. Unfortunately, I first encountered it in an anthology (so my formative recollections of the passage associate it with The Whimsical Christian instead of its ultimate source), and I long ago lent out my copy of Creed or Chaos?, so I can’t verify the reference precisely.

8Granted, he probably wouldn’t have enjoyed some parts of “Planet of the Bass,” but I think we can safely say St. Luke would have approved of the line “Women are my favorite guy.”

9The name Theofilos could mean either “lover of God” or “beloved of God.” The latter seems a little more natural; we might expect Φιλόθεος [Filotheos] if the former were the intended meaning. However, the difference is minimal and may not be significant, or the ambiguity may have been deliberate. Assuming it was a personal name, a fairly close English equivalent would be Godwin: The Anglo-Saxon word wine (pronounced not as if to rhyme with “mine,” but as if to rhyme with the “King’s English” pronunciation of “cleaner”) was a poetic word for “friend,” usually appearing in names as a suffixed -win or –wyn (but not always—e.g., Winifred also contains the word).

10Unfortunately, while Simeon is far from an obscure name and the particle ben “son of” is as common as mud, I was unable to find vowel pointing for Boethus, since search engines suck now.

11The names of the twelve tribes, from left to right and top to bottom, are as follows: Levi, Simeon, Reuben; Zebulun, Issachar, Judah; Gad, Naphtali, Dan; Benjamin, Joseph, Asher.