Or: A Belated Introduction to Luke

I’ve at last gotten a bit of breathing room, and can return to a long-postponed duty: introducing what Luke’s deal even is! Here goes.

The Tradition of Saint Luke

A portrait of St. Luke in the St. Augustine

Gospels, a 6th-c. evangeliary now housed in

Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University

—one of the oldest extant European books.

(Note: Here, as in a few other places, I’m using “tradition” in the small-t sense: ideas that have been passed down in the same manner as, well, all history, but not necessarily part of holy Tradition in the sense of revealed truth.)

The traditional account of the third Gospel is that it was written by St. Luke, a physician from the city of Antioch. Luke was a Gentile who had converted to Judaism, and became a Christian as the faith spread along the Mediterranean littoral, presumably some time in the 40s of the first century; he soon became a companion and aide of St. Paul, and it was from this association that Luke’s writings acquired the status of apostolic authority they went on to enjoy. He wrote both his Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, based on interviews with members of the primitive Church and his own travel diaries.

On this view, Luke is most securely dated by Acts. (The large proportion of Marian material uniquely present in Luke does suggest an interview, if not an outright acquaintance, with her, but it does not follow that his Gospel was written before the end of her life.) Closing as it does before the end of St. Paul’s trial before Nero, Acts ends when it does because when it was written, that trial had not in fact concluded. This dates the completion of Acts to around 64 or 65 at the absolute latest,1 since the Great Fire of Rome took place in 64, and Christians were scapegoated for it and outlawed not long thereafter.

The Gospel, alluded to in the opening of Acts as “the former treatise I have made, O Theophilus,” would presumably have been composed somewhat earlier. How much earlier is difficult to say. The author says in the first verse of his first book that “many have taken in hand to set forth in order a declaration of those things which are most surely believed among us,” and that he is now doing the same, which sounds like it includes Matthew and Mark. We lack absolute dates for them too, so this isn’t as helpful as we might wish; but we can approximate that the Gospel of Luke might have been written some time in the 50s of the first century (probably on the later side, if we are giving Luke time to have read both Matthew and Mark before composing his own work).

Modern Critics on Luke

The modern critical consensus is not absolute, partly because it involves all three Synoptic Gospels, not Luke alone. It generally accepts that Luke and Acts are of the same pen, and places the two books in the last couple decades of the first century2; its author (who may or may not have been called Luke—in any case he is never named in either book) is allowed by most scholars to have met St. Paul. However, his failure to mention the composition of the epistles in Acts, and claimed contradictions between Lucan theology and Pauline, up to and including misrepresentations of the latter by the former, are seen as decisively against the idea that the author of Luke-Acts was a companion of Paul’s.

Anonymous depiction of the finding of Christ

in the Temple (Luke 2:41-51)3

from Kraków, Poland.

I find these objections to the traditional view dreadfully silly. Even supposing we granted that Lucan theology contradicts St. Paul—which I do not, but one thing at a time—why on earth should we suppose that “being a companion of Paul” must go together with “always evaluating and describing things exactly as Paul would”? A fraud who wanted to pose as St. Luke would probably do so; indeed, he would probably scrupulously pepper his books with Paulisms to make it more convincing—especially his Gospel, since he would thus be validating Paul’s ministry as an authentic apostle to boot! The presence of such devices might not tell us much, since real contemporaries do also quote each other; but their absence ought to point to thoughtless, low-effort forgeries, and whatever else they are, the books of Luke and Acts are not thoughtless or low-effort pieces of literature.

And as for the epistles, is there any particular reason the historical Luke would have mentioned them? If anything, their absence from Acts again supports the authenticity of the traditional view (or a view as like it as makes no difference); for anyone writing pseudepigraphically and a few decades removed from Paul’s time—when the Paulines had become well-known and were widely esteemed as Scripture—would have been sure to mention them, both to give his own work verisimilitude and to slake the curiosity of his readers.

But when the letters were written, they were addressed to churches or specific persons, and were mainly those churches’ or persons’ business; in several cases, they were mere forerunners to an in-person visit from the apostle. They were not, at the time when they were composed, conceived of as “parts of the New Testament” which it’d be helpful to document.4 After all, taking special note that Paul wrote a letter to such-and-such a church or person doesn’t actually serve the purpose of the book of Acts all that well. Its aim is to exhibit the gospel spreading from “Jerusalem, and all Judæa, and Samaria” to “the uttermost part of the earth,” handily symbolized by arrival in Rome; it’s not addressed to our curiosity about when Paul wrote what.

A Digressive, and Lightly Recursive, Rant

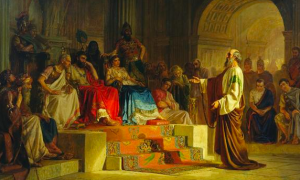

The Apostle Paul on Trial (1875), by Nikolai

Bodarevsky. This event is from Acts 26; Paul

here makes a defense to Herod Agrippa II,

great-grandson of Herod the Great, and Festus.

These kinds of poorly thought-out takes appear endlessly in New Testament criticism, and they drive me up the wall. (I’m considering writing an addendum to this introduction to discuss a project currently being undertaken about the lost Gospel of Marcion that, as far as I can tell, is, mathematically—and no, that isn’t a joke—one of the worst ideas I’ve ever heard of.) The late John A. T. Robinson, in the final pages of his excellent, if now somewhat old, book Redating the New Testament, quotes a very sensible passage from a contemporary of his:

In my world, if The Times and The Telegraph both tell one story in somewhat different terms, nobody concludes that one of them must have copied the other … But in that [scholarly] world of which I am speaking this would be taken for granted. There, no story is ever derived from facts, but always from somebody else’s version of the same story. … In my world, almost every book … is written by one author. In that world almost every book is produced by a committee, and some of them by a whole series of committees. … In that world no prophecy, however vaguely worded, is ever made except after the event. In my world we say, “The first world-war took place in 1914-1918.” In that world they say, “The world-war narrative took shape in the third decade of the twentieth century.” In my world men and women live … seventy, eighty, even a hundred years—and they are equipped with a thing called memory. In that world (it would appear) they come into being, write a book, and forthwith perish, all in a flash, and it is noted of them with astonishment that they “preserve traces of a primitive tradition” about things which happened well within their own adult lifetime.5

“Idiot” in English originally referred to the

mentally disabled, so no, the Book of Common

Prayer in saying this was not being funny

… originally.

Lest I be misinterpreted here: I’m not a fundamentalist, nor even a strict inerrantist. I also do not consider the traditional ascriptions of the books of the Bible to be part of the holy Tradition that I am in conscience bound, as a Catholic Christian, to accept. Even if I did consider the ascriptions part of capital-T Tradition, I’d be willing to highlight ways the available evidence is compatible with such a belief, in the interest of scholarly accuracy; but I’d also consider it flatly ridiculous to advance a positive religious belief, to people who don’t share a positive affirmation of that religion, as evidence for an academic conclusion (which would, for them, be nothing more than a bald assertion). One part of honesty is not only saying what your conclusions are but how you got to them—it’s the same principle as “showing your work” in maths. Using a fallacy to reach a true conclusion may get you to an answer that’s in fact correct, but that’s luck, not insight; it doesn’t make fallacies more reliable.

The point is that, in principle, I take no issue with finding the old ascriptions implausible, nor with formulating, publishing, or accepting new theories. I myself subscribe to some. I don’t think Hebrews is by Paul, or that II and III John are by John. I’ve admittedly moved back toward thinking that II Peter is by Peter, but I long subscribed to the current majority academic view that it isn’t. Neither the inspiration of the New Testament nor honest scholarship need to be at stake in drawing either conclusion.

If I May Get Unduly Personal About It for a Minute

Nevertheless. To speak bluntly for a moment: I find it extremely difficult to avoid the feeling that some of the assumptions made by New Testament critics serve one of two primary purposes: 1. that of fitting in with fashionable scholarship (academia has fashions just like anywhere else, after all); or 2. that of fending off the dreadful possibility that there might be something in the New Testament. I hope my problem with reaching a conclusion in order to sit with the cool kids at lunch needs no explanation. And my problem with the other possibility (always supposing my suspicion is correct) is not that such behavior is impious; actually, I don’t much like commenting on that type of thing, it feels intrusive. No. My problem with attempting to fend off the possibility that there might be something in the New Testament is this: The fear of that possibility, though I find it sympathetic, is irrelevant to what the facts are about the New Testament. My problem is that determining in advance to avoid a conclusion is unscholarly.

Questions about how reliable the New Testament is, as far as I can tell and in our day and age, tend in the last resort to come down to the fact that it reports miracles. Accepting the veracity of such reports is treated as naïve, credulous, fatally uncool. But scholarship, just as such, does not tell us that miracles don’t happen. That is a question we must answer on other grounds.6

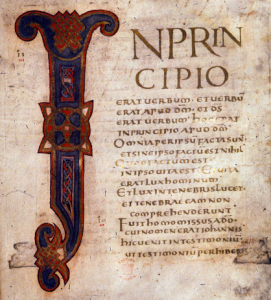

The opening page of the Gospel of John in the

Athelstan Gospels, a.k.a. the Coronation

Gospels (10th c.), probably a gift to King

Athelstan of England from Otto I of Saxony.

We may bring that answer to our scholarship, of course; or rather, we have no choice: We have to answer the question of what we are willing to accept could, or couldn’t possibly, be factual.8 But our answer should be frankly avowed as a presupposition, not brought in unannounced and presented as if it were part of proper scientific procedure. This is especially so since what’s at stake is a philosophical assumption about the possible—not a scientific one about the actual. Reality, having nothing to prove, is well known to indulge itself in many implausibilities.

The same up-front statement of assumptions ought to go for supernaturalists as for naturalists, of course. That said, as a rule, I haven’t found supernaturalists shy about highlighting their presuppositions, if they have even the mildest inclination toward rational argument. (Small wonder, maybe, that so many of us who grew up in evangelical circles in the 1990s and 2000s so unexpectedly turned toward the liturgical and mystical branches of the faith. I know if I’d heard the word “worldview” one more time before I converted, I might have had a nervous breakdown.)

An entrance to the cave known as 4Q, which

originally held most of the Dead Sea Scrolls (if

“worldview” comes up, you also have to have

some archæological thing vaguely nearby).

In any case, most excellent Theophilus, I will be continuing this in my next post. In the meantime, I wish all my readers a most blessed Easter.

Footnotes

1It could, however, have been earlier; there is a fairly ancient tradition that St. Paul’s trial before Nero ended in acquittal, and that he did then take his hoped-for trip to Hispania, all in about 61-63. After this, the Great Fire occurred, and St. Paul was executed after returning from Hispania to Rome.

2Or even in the first decade of so of the second century, if they really want Daddy Rudolf Bultmann to tell them what a good boy they are.

3The sword in the heart of the Theotokos here reflects the fact that her loss of Jesus for three days in Jerusalem is traditionally enumerated as one of the Seven Sorrows that fulfilled St. Simeon’s prophecy, also recorded in Luke 2 (back in vv. 34-35).

4Personally, I feel that New Testament critics often make errors of this kind—evaluating its books based on their subsequent historical importance, while failing to take into account the fact that they may not have had such importance at the time. This is quite a natural error to fall into, but (whether or not I am right in seeing it in New Testament critics in general) it is crucial that it be corrected when it occurs.

5Robinson, p. 356 of the Wipf and Stock paperback edition printed in 2000 (originally published in 1976); the quotation is from Adrian H. N. Green-Armytage’s book John Who Saw, a layman’s case for the traditional view that the Gospel According to Saint John was by the disciple of that name, who was one and the same person with the “Beloved Disciple.”

6Indeed, if we were to consult historical criteria alone (i.e., the testimony of witnesses and analyses of earlier scholars than ourselves, weighted by their trustworthiness, itself judged by further criteria), we would probably favor the idea that miracles have on rare occasions occurred. Now, it is often impossible to distinguish in historical sources between miracles proper and what we might call “prodigies”: events which are strictly natural, but require causes and/or circumstances so exceedingly rare that most people take them for miracles, at least at first.7 (The Civil War legend of “angel glow,” which some people have dismissed on the grounds that that would be a miracle, is a “prodigy” in this sense.) But really, this ought to make ancient reports of miracles more credible, not less. It opens the door to a great many miracles being prodigies which their witnesses honestly misunderstood (if it’s really that important to you that they be wrong about this).

7Philosophically, causality is far weirder than we usually expect; in deference to that fact, I’ll mention that there may be no metaphysical difference between a miracle and a prodigy. If so, the real indication that something supernatural was going on with any given miracle would be the accurate foreknowledge of it exhibited by the prophet, saint, or angel who “performed” it. But the real problem is if angels have wings then why didn’t they just fly the Ring to Mo [NOTE: Comment terminated here for becoming too stupid. —ED.]

8Which is not to say we may never change our minds, especially if presented with new evidence. However, it will probably behove us—not so much out of piety as out of not wishing to embarrass ourselves by saying things in ways that are hard to take back, like the “published book” way—to wait until we have finished changing our minds to write publicly on topics to which those changing beliefs are directly pertinent.