Go here for Part 1, which has textual notes a and b in it, and here for Part 2, which has notes c through n. I’ve posted the Scripture here a third time to save anybody any tabbing back and forth, but again in small type, and this time with only the verses actually used in the Mass reading.

The Prodigal’s Father

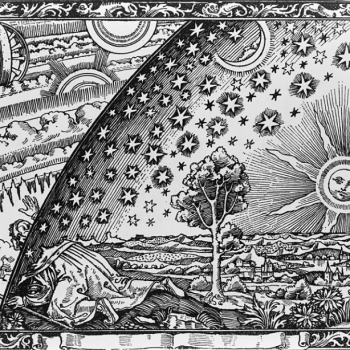

As we resume, I’d like to make a few remarks about this parable. It’s something of a commonplace in Christian circles that fatherhood meant something different in the ancient world than it does today: The respect paid to it was far more august, authoritative, and in some ways remote than modern fathers usually receive, or indeed want. This isn’t to say affection between fathers and children is a modern innovation! But it’s safe to say that reverence, rather than fondness, was expected to be the “top note” in a child’s feelings toward their father. (I’m not here to say whether the change from then to now was good or bad or neither. That’s not what the parable is about; besides, not every analogue for God in the parables is good—among other things, he is compared with a thief in the night and an unjust judge.) However, the power in this parable’s imagery depends on different imaginative associations being attached to fatherhood; it’s not incomprehensible without them, but it loses half its punch.

The Return of the Prodigal Son (ca. 1615-1620),

by Leonello Spada. Note the prodigal’s arms

folded in the posture now traditional to ask for

blessing.

So, there are certain things a respectable first-century Levantine father does not do. In some cases, they’re obvious “moves” in a more heavily patriarchal culture like this one (even if we don’t share them): He doesn’t explain himself to his children, for instance, or at any rate he’s under no obligation to do so. He certainly doesn’t accept insults or back-talk from them.

Others are less obvious; for example, he does not run, not unless it is an emergency and there’s no alternative. Excessive haste does not befit his dignity, for one thing. For another, in order to run in a tunic, you have to hitch up the lower part of it and secure it with a belt—in fact, to gird your loins—which makes you look ridiculous. (Imagine if every time you wanted to run, you had to detach the lower half of your pants, and then tuck the “leftover” parts into your belt loops. Even today’s dad, while he would do that, would do it for the express purpose of embarrassing his children, not by preference.)

Luke 15:1-3, 11-32, RSV-CE

Note: To make it easier to see, I’ve used a capital letter for note l in the text here; however, down in the textual notes, it’s in lower case like the rest. The textual notes dealt with in this installment are in bold in the Gospel passage below.

Now the tax collectors and sinnersa were all drawing near to hear him. And the Pharisees and the scribesb murmured, saying, “This man receives sinners and eats with them.”

So he told them this parable: “There was a man who had two sons; and the younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of propertyf that falls to me.’ And he divided his livingf between them. Not many days later, the younger son gathered all he had and took his journey into a farg country, and there he squandered his property in loosef living. And when he had spent everything, a greath famine arose in that country, and he began to be in want. So he went and joinedi himself to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him into his fields to feed swine.j And he would gladlyk have fed on the podsL that the swine ate; and no one gave him anything. But when he came to himself he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have bread enough and to spare, but I perish here with hunger!m I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me as one of your hired servants.”’ And he arose and came to his father. But while he was yet at a distance,n his father saw him and had compassion,o and ranp and embraced him and kissed him. And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ Butq the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe,r and put it on him; and put a ringr on his hand, and shoesr on his feet; and bring the fatteds calf and kill it, and let us eat and make merry; for this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’ And they began to make merry.

“Now his elder son was in the field; and as he came and drew near to the house, he heard musict and dancing. And he called one of the servants and asked what this meant.u And he said to him, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has received him safe and sound.’v But he was angry and refused to go in. His father came out and entreatedw him, but he answered his father, ‘Lo, these many years I have served you,x and I never disobeyed your command; yet you never gave me a kid, that I might make merry with my friends.x But when this son of yours came, who has devoured your living with harlots, you killed for him the fatted calf!’ And he said to him, ‘Son,y you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. It was fitting to make merry and be glad,z for this your brother was dead, and is alive; he was lost, and is found.’”

Luke 15:1-3, 11-32, my translation

Note: To make it easier to see, I’ve used a capital letter for note l here in the text; however, down in the textual notes, it’s in lower case like the rest. The textual notes dealt with in this installment are in bold in the Gospel passage below.

All the tax-farmers and sinnersa were were drawing near to him to hear him. And the Pharisees were murmuring, as were the scribes,b saying that “This man receives sinners and eats with them.”

Then he spoke to them in this analogy, saying: “A certain person had two sons; and the younger of them said to his father: ‘Father, give me the part of your substancef that falls to me.’ So he divided his livingf between them. Not many days afterwards, the younger son gathered everything and went abroad into a country a long way off,g and there he scattered his substance, living extravagantly.f When he had spent everything of his own, a fierceh famine befell that country, and he began to fall short; and, making his way along, he affixedi himself to one citizen of that country, who sent him out into his fields to feed pigsj; and he desiredk to fill his innards with the carob podsL which the pigs ate, but no one gave anything to him.

“Then he came to himself and said: ‘How many of my father’s hired hands are overflowing with bread, and here I am starving to death!m—I will get back up, go to my father, and say to him, “Father, I sinned against heaven and in your presence; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired hands.”‘ And he got up and went to his father.

“Yet while was a long way off,n his father saw him and was gutted with pity,o and running out,p he fell on his neck and kissed him. His son told him, ‘Father, I sinned against heaven and in your presence; I am no longer worthy to be called your son’—butq his father told the slaves, ‘Quickly, bring out the finest gownr and dress him, and give him a finger-ringr on his hand and sandalsr on his feet, and bring the grain-feds calf, sacrifice it, and we will make merry eating it! for this is my son who was dead, and he lives again—who was lost and has been found.” And they began to make merry.

“Now, his elder son was in the field; and as he was coming back, getting near the household, he heard harmoniest and dancing, and calling one of the boys over he inquired what this might beu; he told him that ‘Your brother is here, and your father sacrificed the grain-fed calf, because he got him back safe and sound.’v He was enraged, and did not want to come inside. Yet his father came out and called forw him. He told his father in reply: ‘Look, all these years I slave for youx and never bypassed a command of yours, and you have never given me a goat-kid in order to make merry with my loved onesx; yet when this son of yours comes back, who eats your living up with whores, for him you sacrifice the grain-fed calf.’ He told him: ‘Child,y you are always with me, and everything of mine is yours; but we had to make merry and rejoice,z because this, your brother, was dead and lives, and was lost and is found.'”

Return of the Textual Notes

After looking one up, I decided not to put

a picture of a spleen here, you’re welcome.

o. had compassion/gutted with pity (ἐσπλαγχνίσθη [esplanchnisthē]): The noun from which this verb is derived, σπλάγχνον [splanchnon], is related to the English word spleen, but is a little more generic in sense—”internal organs,” “guts,” or (in the archaic sense) “bowels” is fairly close. However, unlike in modern times, where the heart is the seat of most emotions and especially feelings like affection and pity, in the ancient world it was the “bowels”—sometimes the kidneys specifically—which were the seat of sympathy. Σπλάγχνον is occasionally translated “heart” for this reason, which I like in theory, but then we run into the facts that καρδία [kardia] “heart” is a fairly common word in the New Testament as well, and that σπλάγχνον can have other implications too. I therefore tried to used a phrase that had the right kind of generic-ness about what organ was concerned, but at least stayed tied to organs in how it was phrased.

p. ran/running out (δραμὼν [dramōn]): See the introductory matter above. Fathers don’t do this in antiquity; except, this father does.

Also, there’s something I forgot to mention in my last, when I highlighted the two occurrences of μακράν [makran]. “While he was a long way off, his father saw him”: this implies that the father was outside, and further suggests that the father was looking for him—awaiting him, expecting him to come back.

q. .’ But/—but (… δὲ [de]): Normally, a little word like this wouldn’t merit translation per se. In a majority of cases, δὲ is what’s called a discourse particle, something that gets inserted into speech less for any actual meaning and more for flow or to hint that the speaker may have paused but isn’t finished,1 while occasionally δὲ occurs in contexts where it has a contrastive function, and therefore receives a translation like “but” or “yet” (all this being why I’ve included the preceding punctuation as part of what’s being “translated” here).

What I find so striking here is this. We know that the returning son has planned out what he’s going to say, including the severely demoted position he’s going to ask for; he starts to recite his rehearsed speech—and his father interrupts him. Maybe his father could tell what the boy was going to say, maybe not; he doesn’t care. He knows what the boy has said, and that that’s no mood to be bringing to the party they need to throw right now.

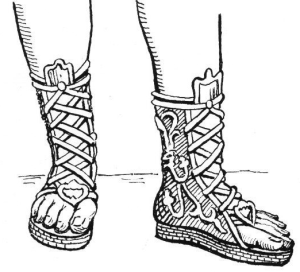

r. best robe … ring … shoes/finest gown … finger-ring … sandals (στολὴν τὴν πρώτην … δακτύλιον … ὑποδήματα [stolēn tēn prōtēn … daktülion … hüpodēmata]): All three of these things, as even a casual reader will probably guess, are marks of honor. (Two of them sound opaque or silly in a hyper-literal translation: στολὴν τὴν πρώτην literally means “the first robe,”, first [in quality] being understood; meanwhile, δακτύλιον really just means “finger-y [thing]”!)

The ring and sandals are particularly noteworthy, however. The text does not identify this as a signet ring specifically, and many different kinds of rings were worn in the ancient world—and often elsewhere than the fingers (toes, ears, arms, nose), hence the specificity. But, if it was a signet ring, this would indicate authority to make binding legal agreements on behalf of the household (which would be quite the compliment, even if the ring were only worn honorarily and for a single night).

More important still are the sandals.2 Whether the father can tell or not, we know that the son was going to ask to be ranked with the hired help. This segment of the staff aren’t slaves (unless you accept the idea of wage slavery3), but they’re not high above it; in fact, in the class hierarchy, “hired hands” are probably below some slaves—at least below the higher echelon of slaves4 belonging to the upper crust, fancy people like your Herod Philips and your Pontiuses Pilate. If you’re wondering what slavery has to do with anything, the answer is that while there were exceptions, the norm for slaves was to go barefoot. Sandals (especially the kind of sandals one would naturally pair with “the finest gown”) marked a free person.

An illustration of buskins, a type of

sandal-boot familiar in the Roman times.

s. fatted/grain-fed (σιτευτόν [siteuton]): Very much by chance, at any rate by no ingenuity of mine, the literal translation of σιτευτόν is currently also a better match to the “vibe” of the word! A calf that was grain-fed would, in fact, be fattened. (The upsetting parallel of foie gras doesn’t need me to repeat it, but I don’t think you could do that with calves or without more modern tech than they had back then—and if I’m mistaken, don’t tell me, I don’t want to know!) But of course nowadays, the fashion is all of the “getting back to nature” variety (regardless of how true that actually is about any product), so that “grain-fed beef” sounds more luxurious to our ears than “fattened beef.”

t. music/harmonies (συμφωνίας [sümfōnias]): This word does specifically mean “harmonies,” as distinct from “melodies” or “music [in general],” though obviously it does mean the latter contextually.

A depiction of a musician (ca. 1350-1150 BCE)

from Megiddo, playing what is probably

a kînnaur,5 the Canaanite/Hebrew version of

the lyre (probably).

u. what this meant/what this might be (τί ἂν εἴη ταῦτα [ti an eiē tauta]): My translation here is again pretty literal; what it translates is rather interesting, because it is a rarity in New Testament Greek: the optative mood.

We’re familiar with the indicative mood, (which we usually call “declarative” in English), the imperative mood (we recently discussed the rare third-person imperative), and the interrogative mood (which doesn’t appear in Greek, but does in English). Ancient Greek also has two of what are called irrealis moods—moods that refer to things which are in some sense hypothetical or unknown.6 They are the subjunctive, which is the more generic irrealis mood, and the optative, which usually expresses a wish or hope. However, verbal moods occasionally have other uses, especially when describing indirect speech; English does something similar with what’s called the “sequence of tenses.”

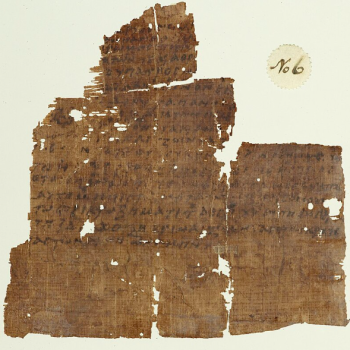

All this mostly applies to Classical Greek proper. The New Testament, though written in Ancient Greek, is not written in the Classical phase of the language; that was spoken in roughly the sixth to fourth centuries BCE—the Greek of Sophocles, Aristotle, and Zeno. After Alexander spread Greek from Macedon to Margiana, a lot of its finer details (both grammatical and in vocabulary) wore down; the Koiné or “Common” Greek of Jesus’ day was a noticeably simplified language, from which optative had almost completely dropped out, except in a few stock expressions like μὴ γένοιτο [mē genoito] “may it not come to be,” or more idiomatically “God forbid.” But Luke has exceptionally good Greek, and almost all the optatives in the New Testament come from his pen, in either the Gospel or the book of Acts. This is one of them, and exemplifies the indirect-question use of the optative.

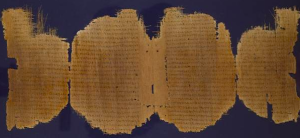

Papyrus 45, a 3rd-c. manuscript containing

parts of chapters 11-13 of Luke.

v. safe and sound (ὑγιαίνοντα [hügiainonta]): Literally this word means “being healthy,” but that felt far too stilted to be passed off as readable English, and the stock phrase was just crying out to be used.

w. entreated/called for (παρεκάλει [parekalei]): Παρακαλέω [parakaleō] can mean “to send for, summon,” but has more meanings in the “urge, beseech, entreat” family. (Even in Modern Greek, παρακαλώ [parakalō] means “please”—the interjection, not the verb.) The title “Paraclete” for the Holy Ghost is a transliteration of παράκλητος [paraklētos], which comes from … well, you get the idea.

x. serve you … make merry with my friends/slave for you … make merry with my loved ones (δουλεύω σοι … μετὰ τῶν φίλων μου εὐφρανθῶ [douleuō soi … meta tōn filōn mou eufranthō]): To a modern reader, there may seem to be some reason in the elder son’s complaint (even if Christianity has sufficiently influenced our culture’s ethical sense to make us feel vaguely that he should be nicer about his brother coming back). We may remember that this is a much more father-as-authority sort of culture, and recognize that the parable wouldn’t necessarily strike ancient ears the way it strikes ours, sure; but I have a shrewd hunch that deep down, most of us feel that this an oddity of the ancient world we’ve done well to discard, and therefore continue to feel comfortable harboring a little sympathy for the elder brother.

“Fëanor Did Everything Wrong” would be closer.

Untitled drawing of Fëanor threatening his

half-brother Fingolfin (2007), by Tom Loback,

used under a CC BY-SA 2.5 license (source).

As I said at the beginning, I’m not here to argue that ancient familial mores were better than ours are now—by and large, I think the opposite! But what’s important here is, I suspect that that sympathy with the elder brother causes us to miss something in this parable. I’d like to bring that something out a bit; let’s break it down.

All these years I slave for you—Wow, okay; your father’s a slave-master now? Which, yes, he literally was according to the wording of the parable; but that doesn’t mean it’s how he treated his children. The only other evidence we have on that subject, i.e. the rest of the parable, very much suggests the opposite, and there was certainly nothing abnormal about sending your children to do at least some outdoor work, any more than there is today about telling your kid to mow the lawn. One begins to wonder whether it is only the younger of the two sons who takes his father’s gentleness for granted. But this bit of bad grace is only the beginning …

To make merry with my loved ones—Here we hit the text’s real “ouch”: the elder brother contrasts “you,” his father, with “my loved ones.” Now, there is more wiggle room in the Greek τῶν φίλων μου than in the English “my loved ones”; φίλος [filos] is more usually translated “friend.” But that isn’t … what the word means. Φιλέω [fileō] means “to love”—it’s perhaps the most generic term for love in Greek. The way the text is phrased doesn’t demand that we read this as a statement of hostility on the son’s part, but it is uncomfortably available, uncomfortably credible.

y. Son/Child (Τέκνον [Teknon]): Remembering the gravity and grandeur that attached to fatherhood at this time, in combination with helps drive home how gentle is the reprimand here, if it even is a reprimand. The word τέκνον, “child”—literally “born [one]”7—may be a soft hint, reminding the son of his proper place; and this, this might-be-a-hint, is the most rebuke his father makes.

z. all that is mine is yours. It was fitting to make merry and be glad/everything of mine is yours; but we had to make merry and rejoice (πάντα τὰ ἐμὰ σά ἐστιν· εὐφρανθῆναι δὲ καὶ χαρῆναι ἔδει [panta ta ema sa estin: eufranthēnai de kai charēnai edei]): And here we go! The father in this parable has run in public, he’s borne severe insults from both his sons, to his face, and now, he explains himself to his son. He does so in two parts.

The Ghassulian star (ca. 3500 BCE), a piece of

cave art from the early Canaanite Bronze Age.

This has very little to do with the parable, I just

came across it and thought it was really cool.

“All that is mine is yours.” In other words, he isn’t re-dividing the inheritance as if nothing happened; that decision is going to stand. Once his father dies—maybe before then (more on that in a sec)—the younger brother is going to get only what the elder brother chooses.

“But we had to make merry”: and here, I’ll actually argue a little bit in favor of my translation over the RSV’s. The word ἔδει, originally from δέω [deō] “to bind, fetter, fasten,” was not merely a verb for something being fitting or appropriate. It was a term for strict obligation, necessity, even logical consequence. The total effect of these two phrases is almost that of the father explaining to his elder son why he has taken something out of that elder son’s inheritance to celebrate the return of his younger son. This father doesn’t stand on his dignity in the slightest, doesn’t even maintain his dignity; he just wants to be with his sons.

Footnotes

1In English, words like um, now, so, well, anyway, and—as of the last couple decades—like, are good examples of discourse particles. Most of them also have an actual semantic function, but that function can be soft-pedaled or even (for all intents and purposes) dropped for the sake of their discursive function.

2Sandals—specifically not shoes. Shoes were not common in the ancient Mediterranean: Most materials for making shoes are going to wear out quickly in a world with neither mechanical transportation nor rubber, and in a world without assembly-line production and sewing machines and so forth, they’re an incredible pain in the ass to make. Remember, if you can’t mass-produce it, you’re just making the product for whomever wants it, and since shoes are not nearly as adjustable as other kinds of clothing (which in those days were mostly slight variations on “a big length of cloth wrapped around the body in varying styles and degrees of cleverness”), they’d have to be tailor-made. Sandals, though? So flexible—it’s just a thing that’ll cover the sole of a foot about the size of that thing, plus lots of straps and/or strings to hold it on the foot. That’s easy and fast to make, and it’s cheap (so the rapid wear doesn’t matter so much), and one-size-fits-lots (no tailoring)—everybody wins!

3Which we do. But let’s not get sidetracked.

4If the phrase “higher echelon of slaves” makes you feel like someone must be punking you: No, there really was such a thing. The tutors of children of the wealthy, for instance, would normally be slaves, as might a number of other important and highly-trusted members of household staff—valets, accountants, stewards, etc.

5The other name of the Sea of the Galilee, i.e. the Sea of “Chinnereth” or “Gennesaret,” may be derived from the shape of the kînnaur; although the word is masculine in Hebrew, it does take an –oth plural (usually associated with feminine nouns), so the “Sea of Chinnereth” (from Kînnaurauth) might originally have meant something like “the Sea of Lyres” or “the Sea of Harps.”

6Well, technically it has three, because the imperative is an irrealis mood too, strictly speaking. In fact, most moods other than the indicative are irrealis moods. English is a little unusual in having (arguably) two realis moods, the declarative and the exclamatory.

7It is related to the term Θεοτόκος [Theotokos], conventionally rendered “Mother of God” but more literally meaning “God-bearer.”