ARE WE?

No.

Here’s why the question comes up. Although we’re in Year C, which is devoted to Luke, the Gospel this past Sunday came from John 8

St. Luke the Evangelist as depicted in

the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493).

… except, not really. The passage we know as John 7:53-8:11, or “the adulteress pericope,” appears thus in Byzantine manuscripts; in the oldest manuscripts of John’s Gospel, these verses are absent. The Greek New Testatment text supported by the Society of Biblical Literature, which I usually use as the basis of my translations here, doesn’t feature these verses—it goes right from 7:52 to 8:12. (I must accordingly tender my thanks to The Online Greek Bible, from which I got the Greek for this post.) The 7:52-to-8:12 transition makes more sense, in light of the style and flow of John: Chapters 7 and 8 are part of the grand cross-examination that Gospel largely consists in, centered on the autumnal festival of Sukkot (from סֻכָּה [sûkâh] “booth, hut”), to which the episode of the woman caught in flagrante delicto is an interruption, not only failing to follow the theme, but failing really to relate to anything else in the Gospel; and John, unlike Mark and Luke, doesn’t really do detached episodes—everything is woven quite snugly together.

Furthermore, even those manuscripts that include these verses don’t always put them here. Some incorporate it after verse 36 instead of verse 52; others include it, seemingly as an “appendix,” at the end of the Gospel. Others go much further afield for its position: the Gospel of Luke, after chapter 21. This makes a certain chronological sense, fitting in with the rest of the narrative. The Greek of this passage is also more like that of Luke (see note e below especially), which is easier to appreciate since John has quite a distinctive style—elegant, but with an elegance not native to Greek. Incidentally, the last two verses of chapter 21 of Luke read as follows in the King James:

And in the day time he was teaching in the temple; and at night he went out, and abode in the mount that is called the mount of Olives. And all the people came early in the morning to him in the temple, for to hear him.

Weird. That looks a lot like John 7:52-8:2. Oh well, guess we’ll never know what brought that about—if we think the adulteress pericope seems like genuine Scripture, clearly our only choice is to argue that it does belong in John, and that the Textus Receptus is the best edition of the New Testament. (No I’m not salty about this why do you ask.)

This does, however, raise the question of why this passage would be detached from Luke and put in John in the first place! That seems like a pretty random thing to do, doesn’t it?

Making a new home for it in John does seem kind of random; perhaps the person who found the text in isolation simply copied it out as soon as he found it, or at the first place in the text where there seemed to be enough of a break to insert something. As for why it was detached in the first place, there is probably a relatively simple answer to that. The practice of the sacrament of penance was not absolutely uniform in the primitive Church, but there were three sins which the Church was reluctant to absolve: apostasy (i.e., renouncing the faith, usually but not necessarily through an overt act of idolatry); murder; and adultery. Of course, even those churches which would not grant absolution for these offenses considered it their duty to intercede for those who had committed them on the Last Day, and on the other hand, even those which would absolve them imposed heavy, protracted penance before restoring the repentant to full communion.

The rebuke of Nathan and repentance of King

David (incidentally, for adultery and murder)

from the Paris Psalter, a 10th-c. Byzantine

illuminated psalm-book.

The trouble is, the Gospels record Jesus forgiving at least two of these sins, and if the adulteress pericope is authentic to either John or Luke, all three. This is doubtless part of the reason that, when the controversy over the power of the keys came to a head in the 250s with the heresy of Antipope Novatian,1 the conclusion drawn by the Church at large was the lenient one rather than the rigorist—in other words, that all sins without exception could be absolved.2

St. Peter’s apostasy is one of the few acts recorded in all four Gospels, so there was no ignoring that. As for murder, not only was “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” one of the Seven Words spoken from the Cross, it had also been taken up by St. Stephen as he was being martyred; not likely to unseat that either. But the adulteress pericope occurs only once, and is the only example of Jesus plainly forgiving that offense explicitly—there are other passages where fornication or prostitution seem to be in view (like Luke 7:36-50), but pardon specifically for adultery appears unambiguously only here.

It’s therefore possible—to my mind, likely—that some copyist with “more zeal than knowledge” wished to excise these verses. Perhaps he did so but was then stricken in conscience, and re-copied the verses at the end of Luke, causing them to appear between Luke and John (thus enabling them to be further displaced later). Or maybe his conscience was seared, but a later copyist noticed the omission and helpfully added the missing verses, in the same place and with the same results.

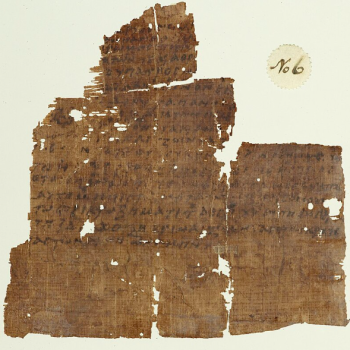

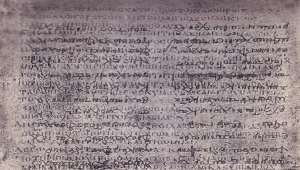

A photocopy of part of the Codex Ephraemi

Rescriptus, a New Testament palimpsest.3

John 7:53, 8:1-11, RSV-CE

They went each to his own house, but Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. Early in the morning he came again to the temple; all the people came to him, and he sat down and taught them. The scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery, and placing her in the midst they said to him, “Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. Now in the law Moses commanded us to stone such. What do you say about her?” This they said to test him, that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. And as they continued to ask him, he stood up and said to them, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” And once more he bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. But when they heard it, they went away, one by one, beginning with the eldest, and Jesus was left alone with the woman standing before him. Jesus looked up and said to her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” She said, “No one, Lord.” And Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you; go, and do not sin again.”

John 7:53, 8:1-11, my translation

And each went to his house, while Jesus went to the Mount of Olives.

At dawn he again arrived in the Temple, and the whole people came to him, and sitting down, he taught them. Then the scholars and the Pharisees brought a woman apprehended for adultery, and, standing her in the middle, they said to him, “Teacher, this woman was apprehended in the act of committing adultery; in the law, Moshe charged us to stone such women—what do you say, then?” (This, they said to test him, in order that they might have something to accuse him of.) Jesus stooped downwards and wrote with his finger on the earth. As they persisted in asking him, he straightened up and told the, “The sinless person among you, be he the first to throw a stone at her.” And stooping back down again, he wrote on the earth.

Hearing that, they went away one by one, starting from the eldest, till he was left alone—and the woman, there in the middle. Straightening up, Jesus said to her, “Ma’am, where are they? No one passed judgment on you?” She said, “No one, sir.” Jesus said, “Nor do I pass judgment on you; go, and from now on, do not sin any more.”

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery,

ca. 1640, Rembrandt—apparently a sketch for

a painting not ultimately executed.

Textual Notes

a. the Mount of Olives (τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν [to oros tōn elaiōn]): Also called Mount Olivet, this is a ridge to the east of Jerusalem, once covered in olive trees. It was already in use as a cemetery during the existence of the Kingdom of Judah, when the First Temple stood, and continues as such to this day.

b. caught/apprehended (κατείληπται [kateilēptai]): This is a (very non-obvious) form of the word καταλαμβάνω [katalambanō], itself a variant of the verb λαμβάνω “to take, receive,” with κατά functioning as an intensifying prefix.4 This verb usually has a literal meaning, but can also be used metaphorically, and is then generally translated “to understand”—grasp or, colloquially, get are good analogues here in English. Apprehend, both in itself and for its similarity to comprehend, therefore seemed like a good translation. (The same word occurs in John 1:5, saying that the darkness has not καταλαμβάνω-ed the light; does it mean “understood”? “accepted”? “overpowered”? “arrested”? The answer to all of these possibilities is “yes.”)

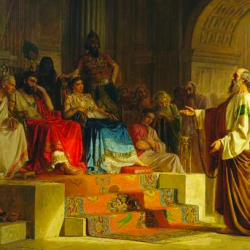

Christ and Sinner (1873), Henryk Siemiradzki.

c. in the act of adultery/in the act of committing adultery (ἐπ’ αὐτοφώρῳ μοιχευομένη [ep’ autofōrō moicheuomenē]): I am very far from being the first person to observe that, traditionally, adultery requires a minimum of two persons, and to wonder aloud where the chap is, then. Of course, there are possible explanations: perhaps the man successfully escaped (we need hardly imagine that the entire group of scribes and Pharisees actually did the apprehending here, all cramming themselves into a single bedchamber to collectively grab the offenders); perhaps he was a Gentile (a Roman soldier, for example), over whom the Sanhedrin had no authority. It is almost as striking that Jesus doesn’t mention the man’s absence, as it is that the man is absent.

d. wrote with his finger on the ground/wrote with his finger on the earth (τῷ δακτύλῳ κατέγραφεν εἰς τὴν γῆν [tō daktülō kategrafen eis tēn gēn]): There seems to be a long tradition of interpreting this as him writing down the sins of those present on the ground. I don’t understand why people think this; to me, it doesn’t sound like Jesus at all.

I have long wondered whether it might be a reference to something else: the sotah ritual, a type of trial by ordeal instituted in the Torah (Numbers 5:11-31) to test a wife for infidelity. Among other things, the ritual involved mixing dust from the floor of the Tabernacle, now the Temple, with water, along with the ink of a prescribed curse written on a scroll and then washed off in the water; shockingly, the curse included the Tetragrammaton, this being the only instance in which the destruction of the Name once written was permitted (and indeed, enjoined).

A fresco in Castelseprio, Italy, depicting

the sotah ordeal. Photo by Wikimedia

contributor Charadron, used under

a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

In combination with the man’s absence, I have to wonder whether this woman was “caught in the act” of adultery. Maybe what really happened was that an obsessively jealous husband caught her doing something that perhaps amounted to proof of adultery in his mind, so that he may have felt justified in saying he “caught her in the act,” and none of the crowd of rabbis and scribes he appealed to felt the need to examine his conclusion. If so, Jesus writing on the ground would be a silent but direct rebuke—a way of saying There is a way of testing her for unfaithfulness instead of just taking that guy’s word for it. Even his silence might be significant in that case, hinting at the use of the Tetragrammaton in the curse, since it was almost never spoken aloud in Jesus’ day.

e. him who is without sin/the sinless person (Ὁ ἀναμάρτητος [ho anamartētos]): Something strikes me about the fact Jesus here uses an adjective (“sinless”), not the prepositional phrase (“without sin”) we’re used to hearing in English. I have no idea what, if anything, to make of this difference; it just sticks out to me.

f. Let him … be the first to throw a stone at her/be he the first to throw a stone at her (πρῶτος ἐπ’ αὐτὴν βαλέτω λίθον [prōtos ep’ autēn baletō lithon]): Here, as in the Our Father, the verb is a third-person imperative—though it has no specific addressee, it is not a suggestion but a command. (This is another, small, point in favor of this passage not belonging in John but in Luke; as discussed last time, Luke has, by and large, the most polished Greek in the Bible, and uses forms like the third-person imperative that are almost, or entirely, absent elsewhere in the New Testament.)

g. Woman … Lord/Ma’am … sir (Γύναι … κύριε [günai … kürie]): Here, the RSV is actually slightly more literal than my translation, but (I’d argue) at the cost of the text’s sense. Γύναι, “woman,” was a perfectly polite form of address in Ancient Greek—not at all like calling a woman “Lady” today. Similarly, in an era where styling oneself “Your obedient servant” to most people was a lot more normal, addressing most males as “My lord” was equally normal. Ma’am and sir are therefore much better practical equivalents of the Greek terms in question than their literal meanings.

h. do not sin again/do not sin any more (μηκέτι ἁμάρτανε [mēketi hamartane]): This presumably applies specifically to the sin of adultery (if its meaning is general, it would read more like a threat than an admonition). Jesus is the Davidic king, and the Melchizedekite high priest: I would assume he has the right in both capacities—certainly in the latter, as the argument of Hebrews implies—to show leniency in applying the Torah. Nevertheless, some acknowledgement of the Torah is called for; neither monarchic nor sacerdotal rule should be exercised arbitrarily, and if we subscribe in any sense to the inspiration of Scripture then the Torah cannot simply be set aside.

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1565),

Pieter Bruegel the Elder. (I mean, he painted it.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder wasn’t himself the

woman taken in adultery, I don’t think.)

Footnotes

1Novatian was a priest in the mid-third century. He wrote several theological works, and helped guide the Christian community in Rome during the relatively brief but severe Decian Persecution (250-251), in the first year of which Pope Fabian was martyred. One of the effects of this persecution was that a large number of Christians apostatized, offering the sacrifice Emperor Decius had mandated; when the emperor died in 251, some of these (known in Latin as lapsī, “the fallen”) sought readmission to the Church, provoking multiple controversies. Novatian was among those who, while allowing that lapsī could become lifelong penitents, argued that the Church lacked the power to forgive their sin (a position Tertullian had also taken). That same year, there was a papal election, long delayed due to the pressure of the persecution. A different priest, Cornelius, was chosen, who espoused the more generous view; those who preferred Novatian and rigorism consecrated him anyway, and tried to get him generally recognized by the rest of the Church, not only in Rome but throughout the Empire. This was mostly unsuccessful, but the Novatianist church (whose members called themselves the Καθαροί [katharoi], “the Pure”—not to be confused with the medieval Cathars) did persist for several hundred years. St. Eulogius, the Patriarch of Alexandria in the late sixth and early seventh centuries (and a personal friend of Pope St. Gregory the Great), wrote against their beliefs, and the fourth-century church historian Socrates relates that, although he refused union with the Great Church, the Novatianist antipope was invited by Constantine to the First Council of Nicæa in 325, and did assent to its definition of the Trinity.

2This was a key development in the doctrine of penance, and not only for the obvious reason. If this had “gone the other way,” then, when the Irish practice of secret confession began to spread to the Continent in the seventh century, it would almost certainly have been stamped out in the long run—can’t maintain the unforgivable-ness of a sin when forgiveness takes place in secret, after all—and there would presumably be no seal of Confession to this day, perhaps no privacy at all. (It wasn’t private in the primitive Church; confessions back then were made in the presence of the whole congregation.)

3A palimpsest is a manuscript, most often written on parchment, that has been re-scraped (from the Greek παλίμψηστος [palimpsēstos], in turn derived from ψάω [psaō] “to scrape, rub”) to remove the initial writing and repurposed for a new document; making parchment was an involved, time-consuming process, so reusing old parchment would have had considerable appeal (especially since parchment, which is made from animal skins, keeps better than papyrus—much the same way leather is more durable than paper). Modern technology allows us to detect traces of the previous document still retained by palimpsests, and often to fully reconstruct them, apart from parts of the manuscript that may be physically missing, of course. The Codex Ephraemi, which is now housed in the National Library of Paris and dates to the fifth century, likely once included the entire New Testament (II Thessalonians and II John either were not included or, more probably, do not survive in this particular copy); along with the Codex Vaticanus in Rome and the Codices Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus in Britain, Ephraemi is one of the “four great uncials,” ancient copies of the whole New Testament written in uncial script (a type of majuscule or “all capitals” script used in Late Antiquity and into the Early Middle Ages). It is speculated—though speculation is all it can be—that Vaticanus and Sinaiticus could be two of the fifty Bibles commissioned by Emperor Constantine in 331.

4This is common in verbs, but not the usual function of κατά—it is a preposition with the base meanings “down from, down along.”