An Introduction Deferred

Russian ikon of St. Luke writing the first

ikon of the Mother of God.

I’d hoped by now to be sufficiently on top of things to circle back around to introducing Luke, but actually what’s happened is that (big first for the blog) I have gotten through the whole alphabet with textual notes. So we’re postponing that intro once again for time!

We have three parables here, the second and third of which are unique to Luke. (There are almost a dozen parables which only Luke records; those of the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son, and the Rich Man and Lazarus are the best-known and most beloved of the bunch.) It has been said, and not without reason, that we might re-title the Parable of the Prodigal Son as “the Parable of the Elder Brother”; the story really is about both sons—and, cough, about their longsuffering father, too—but we close on the elder, ostensibly better-behaved brother, just as we open on the grousing of Jesus’ opponents among respectable, devout, well-educated persons. As I mentioned, we got a lot of textual notes to get through (and we would have more if I hadn’t combined a few closely-related notes more than once!), so, without further ado:

Luke 15:1-3, 4-10, 11-32, RSV-CE

Note: To make it easier to see, I’ve used a capital letter for note l in the text here; however, down in the textual notes, it’s in lower case like the rest. The textual notes dealt with in this installment are in bold in the Gospel passage below.

Now the tax collectors and sinnersa were all drawing near to hear him. And the Pharisees and the scribesb murmured, saying, “This man receives sinners and eats with them.”

So he told them this parable: “What man of you, having a hundred sheep, if he has lost one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness, and go after the one which is lost, until he finds it? And when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders, rejoicing. And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep which was lost.’ Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repentsc than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance.

“Or what woman, having ten silver coins,d if she loses one coin, does not light a lamp and sweep the house and seek diligently until she finds it? And when she has found it, she calls together her friends and neighbors, saying, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found the coin which I had lost.’ Just so, I tell you, there ise joy before the angels of God over one sinner who repents.”

A sixth-century BC drachma from the city of

Naxos, a Greek colony in Sicily. Photo by

the Classical Numismatic Group, used under

a CC BY-SA license (source).

And he said, “There was a man who had two sons; and the younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of propertyf that falls to me.’ And he divided his livingf between them. Not many days later, the younger son gathered all he had and took his journey into a farg country, and there he squandered his property in loosef living. And when he had spent everything, a greath famine arose in that country, and he began to be in want. So he went and joinedi himself to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him into his fields to feed swine.j And he would gladlyk have fed on the podsL that the swine ate; and no one gave him anything. But when he came to himself he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have bread enough and to spare, but I perish here with hunger!m I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me as one of your hired servants.”’ And he arose and came to his father. But while he was yet at a distance,n his father saw him and had compassion,o and ranp and embraced him and kissed him. And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ Butq the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe,r and put it on him; and put a ringr on his hand, and shoesr on his feet; and bring the fatteds calf and kill it, and let us eat and make merry; for this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’ And they began to make merry.

“Now his elder son was in the field; and as he came and drew near to the house, he heard musict and dancing. And he called one of the servants and asked what this meant.u And he said to him, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has received him safe and sound.’v But he was angry and refused to go in. His father came out and entreatedw him, but he answered his father, ‘Lo, these many years I have served you,x and I never disobeyed your command; yet you never gave me a kid, that I might make merry with my friends.x But when this son of yours came, who has devoured your living with harlots, you killed for him the fatted calf!’ And he said to him, ‘Son,y you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. It was fitting to make merry and be glad,z for this your brother was dead, and is alive; he was lost, and is found.’”

Luke 15:1-3, 4-10, 11-32, my translation

Note: To make it easier to see, I’ve used a capital letter for note l here in the text; however, down in the textual notes, it’s in lower case like the rest. The textual notes dealt with in this installment are in bold in the Gospel passage below.

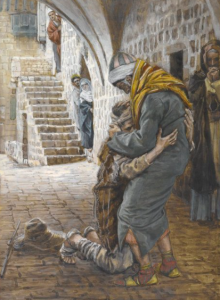

Le Retour de l’Enfant Prodigue [“The Return of

the Prodigal Son”] (1894), by James Tissot.

All the tax-farmers and sinnersa were were drawing near to him to hear him. And the Pharisees were murmuring, as were the scribes,b saying that “This man receives sinners and eats with them.”

Then he spoke to them in this analogy, saying: “Would any person among you who had a hundred sheep and lost one of them not leave the ninety-nine behind in the desert, and make your way to the lost one until you found it? And, once found, he lays it on his shoulders with his hands, and on coming home he will call together his loved ones and neighbors, telling them, ‘Give thanks with me that I found my sheep that was lost.’ I tell you that thus is there joy in heaven over one sinner who has a change of heart,c more than over ninety-nine just sorts who have no need for a change of heart. Or say a woman has ten drachmasd; if she should lose one drachma, won’t she grab a lamp and sweep the household and search diligently until she finds it? And, once found, she will call together her loved ones and neighbors, saying: ‘Give thanks with me that I have found the drachma that was lost.’ Thus, I tell you, joy arisese in the presence of the messengers of God over one sinner who has a change of heart.”

Lambs truly are this cute, but if you’re the sort

of deeply unwell person who needs a downside

to believe something, 1) I’m so sorry we under-

stand each other, and 2) they don’t smell great.

And he said, “A certain person had two sons; and the younger of them said to his father: ‘Father, give me the part of your substancef that falls to me.’ So he divided his livingf between them. Not many days afterwards, the younger son gathered everything and went abroad into a country a long way off,g and there he scattered his substance, living extravagantly.f When he had spent everything of his own, a fierceh famine befell that country, and he began to fall short; and, making his way along, he affixedi himself to one citizen of that country, who sent him out into his fields to feed pigsj; and he desiredk to fill his innards with the carob podsL which the pigs ate, but no one gave anything to him.

“Then he came to himself and said: ‘How many of my father’s hired hands are overflowing with bread, and here I am starving to death!m—I will get back up, go to my father, and say to him, “Father, I sinned against heaven and in your presence; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired hands.”‘ And he got up and went to his father.

“Yet while was a long way off,n his father saw him and was gutted with pity,o and running out,p he fell on his neck and kissed him. His son told him, ‘Father, I sinned against heaven and in your presence; I am no longer worthy to be called your son’—butq his father told the slaves, ‘Quickly, bring out the finest gownr and dress him, and give him a finger-ringr on his hand and sandalsr on his feet, and bring the grain-feds calf, sacrifice it, and we will make merry eating it! for this is my son who was dead, and he lives again—who was lost and has been found.” And they began to make merry.

A popular ring-type in antiquity were cameo

rings, distinct from but not unlike signet

rings. Photo by Wikimedia contributor geni,

used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

“Now, his elder son was in the field; and as he was coming back, getting near the household, he heard harmoniest and dancing, and calling one of the boys over he inquired what this might beu; he told him that ‘Your brother is here, and your father sacrificed the grain-fed calf, because he got him back safe and sound.’v He was enraged, and did not want to come inside. Yet his father came out and called forw him. He told his father in reply: ‘Look, all these years I slave for youx and never bypassed a command of yours, and you have never given me a goat-kid in order to make merry with my loved onesx; yet when this son of yours comes back, who eats your living up with whores, for him you sacrifice the grain-fed calf.’ He told him: ‘Child,y you are always with me, and everything of mine is yours; but we had to make merry and rejoice,z because this, your brother, was dead and lives, and was lost and is found.'”

Textual Notes

a. tax collectors and sinners/tax-farmers and sinners (οἱ τελῶναι … οἱ ἁμαρτωλοὶ [hoi telōnai … hoi hamartōloi]): These two categories have been explained to within an inch of their lives in countless sermons, so let’s explain them again, but in reverse order for the sake of being difficult. (Given the length of this post, I’ve placed less-essential information in paragraphs in small type.)

“Sinners,” then as now, seems to have been used for persons widely believed—on good, bad, or no evidence, and whether it’s anybody else’s business or not—to be guilty of whatever sins are considered unmentionable by polite people. Cultures with strict mores about sex tend to put most if not all sexual transgressors into this category, and “sinners” may simply be a way of saying “prostitutes and the men who buy sex from them.” I mention the latter, because the masculine plural is used in the text, ἁμαρτωλοὶ, which in Greek indicates either an all-male group or one of mixed sex; an all-female group would be ἁμαρτωλαὶ [hamartōlai].

One might argue that it could instead mean male as well as female prostitutes. Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, that might be true; however, it doesn’t seem very likely in Judæa. Prostitution was derided, legally regulated, and seen as morally sketchy, pretty much anywhere you went in classical antiquity, but Judæa was one of the few places that thoroughly and unambiguously disapproved of prostitution to the point of banning it outright (that is, in the Torah; Roman law, which was actually in force in first-century Palestine, allowed it). A mixed-sex group of sex workers isn’t an impossible translation here by any means, but I think the “hookers and the hooked” interpretation is more historically credible.

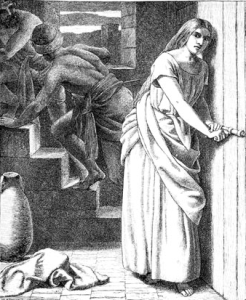

Rahab Receiveth and Concealeth the Spies (1881),

by Frederick Richard Pickersgill, depicting

a Biblical example of a prostitute.1

Tax collectors, or “tax-farmers” as I’ve made it, were known as pūblicānī in Latin (roughly equating to “public servants” or “officials” in literal terms, but applied specifically to the taxman), which is why some translations render τελῶναι as “publicans.” We obviously still have tax officials today, but we don’t have τελῶναι as such: that office was created for a pretty different society.

Collecting taxes was surprisingly difficult work in the ancient world. Commerce wasn’t the main source of most people’s income, and said income often wasn’t in the form of currency anyway. Commerce existed, certainly; think of Lydia, the “seller of purple” from Acts 16. But it wasn’t central the way it was in the modern economy One corollary of this was that income tax was not really a thing the ancient world did, at least not as a matter of course; sales tax and property tax were more normal. Sales were normally effected by means of coins—easy enough to tax that.

And property tax? Most people worked either by getting raw materials from the environment, or by turning those raw materials into something to use or sell. (This even applied, indirectly, to the wealthy; their wealth typically came from owning large agricultural estates and selling excess produce.) The upshot of this was, a large proportion of most people’s assets were “in kind”: wheat, slaves, acres of vintage, clothes, weaponry, you get the idea. Nonetheless, it was overwhelmingly more convenient to do accounting in terms of coinage, since coins were 1. a medium of exchange, applicable to every “kind” without distinction,2 and 2. what you paid the army in (since we are talking about taxes). The upshot of this was that, broadly speaking, you’d need a person’s net worth to be appraised first, and then it could be taxed.

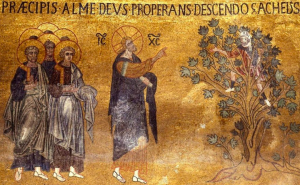

Jesus speaking to Zacchæus in the sycamore

tree—an 11th c. mosaic from St. Mark’s

Cathedral in Venice.

Enter the pūblicānus. Whoever he was, he had won the right to do all this math on the state’s behalf—and the word “won” is not a metaphor: The right to do this was auctioned off by the Roman government. Furthermore, the pūblicānus generally paid the required tax revenue to the government in advance (so he was probably fairly well-off already); in exchange, he was empowered to “reimburse” himself by collecting taxes from the populace retrospectively, as it were—aaand anyone who grasps the concept of cheating, no matter how vaguely, can probably see where this is going!

Besides the obvious opportunities and incentives for financial corruption, and the fact that the list “Times When the IRS Is Popular” basically begins and ends with While a person is watching “The Untouchables” anyway—even beyond that, tax-farmers were extraordinarily unpopular in Judæa, because they were collaborators with an idolatrous foreign empire, exploiting fellow Jews. Both selfishness and sociability, both self-preservation and religion, conspired to make τελῶναι despicable.

Regardless, given the sheer amount of calculation that would be needed even to be an honest tax collector,3 this means τελῶναι/pūblicānī would normally have come from another ancient social class that we do-and-don’t have any more.

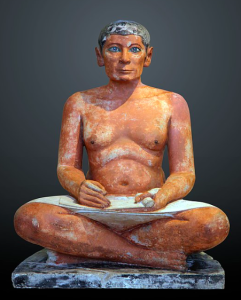

The Seated Scribe (ca. 2600-2300 BCE),

sculptor unknown—Old Kingdom Egyptian,

depicting a scribe. Photo by Rama, used

under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

b. scribes (γραμματεῖς [grammateis]): Scribe was not just a job description in this era; it was a respected social class and had been since the Bronze Age, which was the ancient world’s own “ancient world,” as it were.

In particular, the Roman and Jewish ideals of masculinity were both bound up with the concept of refinement and intellectual accomplishment—more so than the Greeks’ was, and far more than any “barbarian” cultures’ notions of masculinity. For the Romans, the great prize was ōtium, which meant “leisure” in the sense of Josef Pieper’s famous book, Leisure: The Basis of Culture. Ōtium was an opportunity, created by freedom from or withdrawal from both the struggle for subsistence and public service (another next-most-honorable thing in Roman society), that allowed time for literary, scientific, and philosophical pursuits. Meanwhile, for the Jews, Fiddler on the Roof‘s “If I Were a Rich Man” is, forgive the pun, pretty much bang on the money:

If I were rich, I’d have the time that I lack, to sit in the synagogue and pray,

And maybe have a seat by the eastern wall;

And I’d discuss the holy books with the learnèd men

Seven hours every day,

And that would be the sweetest thing of all.

The Fiddler (ca. 1913), by Marc Chagall

(public domain in the US).

However, even among Romans and Jews, all this did not mean that scribes were the upper class. Scribes were upper-class adjacent, certainly. But part of the usual idea of the uppermost class, in this civilization as in most, was “being so rich you didn’t have to work.” In Rome, that meant the patricians, a hereditary aristocratic class from whom the Senate was drawn. In Judæa, the upper-class ideal was a little bit less usual: being a Levite was hereditary, being a rabbi was not; both were points of entry to the uppermost class, but both required something more in addition, ideally a seat on the Sanhedrin (the governing body of Judaism, which decided issues of halakhah or religious law4). Conversely, while being a scribe was a respectable job, it was, in the last resort, a job. It could include pretty workaday duties, more secretarial than academic. Scribes might be minor nobility, or might be of humbler origins, and the expectation of earning their way was probably more heavily laid upon the latter. (Remember, too, that this was a time when most people could not write, and even those who could might prefer to hire an amanuensis to take dictation for them.)

Go to these links for Part 2 (notes c through n) and Part 3 (notes o through z).

Footnotes

1I have long been, and am still, irked by the way many people treat prostitution as anything other than what it is: having sex for money; which is not—to my mind, very obviously is not—a general breakdown of human integrity, or an irrevocable mark of shame, or anything like that. I accept the very ancient (and for once, the hyphen is justified) Judeo-Christian belief that prostitution is one of the things we are able do that is wrong to do; and? So is cheating on a math test. So is murder. So is breaking a promise to meet someone for lunch by being careless about the time. So is publicly humiliating someone who trusts you just for a laugh. In other words, “being wrong” really doesn’t tell you all that much about an act! For Christians in particular, there is apparently exactly one sin that cannot be pardoned, but that one is so mysterious, there’s debate to this day what exactly it consists in, because it’s not on any of the normal lists of sins; and the idea that anything else is unforgivable ought to be laughable to any Christian.

2This is after all one of the basic advantages of coinage. Inflation might turn yesterday’s denarius into today’s two denarii, and that’s annoying to keep track of and treat systematically; but it’s still easier to deal with inflation of denarii, which at least dutifully sit still, than with a “system” that can have entries as dissimilar as one bushel of wheat, four chickens, a glazed drinking bowl, an unglazed drinking bowl, and five yards of linen, and try and render that into anything even approximating equitable accounting practices.

3There must have been two or three of these, in a state the size of the Roman Empire. I assume.

4This is not the same sort of thing as the synods or councils of Christian history. Those are occasional gatherings, and are summoned to address a specific, usually theological, issue. The Sanhedrin, on the other hand, was a body that met regularly, and was more a court of law than a place for hammering out theology. Halakhah is the application of religious law, particularly ritual law. The interpretation of kashrut, or Jewish dietary laws, is an example: when Judaism came to the US, there was some uncertainty about whether bison should be regarded as clean, since they appeared to meet the requirements set forth in the Torah, but, being New World animals, there was no precedent either way (the consensus view today is that bison may be eaten, though of course the other kashrut must be followed in slaughtering and preparing bison like any other animal). Another example, alluded to in John 7, is the question of which duty takes precedence if a male child’s eighth day, when he is supposed to be circumcised, falls on the Sabbath.