Saint Paul Needs a Prequel Miniseries

I wound up with about twice as much “front matter” in this post as I expected! Counting the heading right above this paragraph as the first, the passage proper begins after the fifth heading. Skip to there if you want to jump right in.

We all “know about” St. Paul, to the point that none of us know about him. I am in no position to offer an adequate primer on him here and now. Even a summary of what we do know would be hard pressed to do that knowledge justice. He easily ranked beside Plato or Cicero in intelligence, passion, erudition, and idiosyncracy, not to mention long-term influence.

I was going to put an ikon of him here,

but then it struck me that

St. Paul would probably prefer this.

That said, the reader doesn’t need to know a lot about him for this passage to make sense. It’s more interesting and resonant if you have some backstory, but it’d perfectly comprehensible even if it were anonymous. However, I would like to highlight one thing that this passage brushes up against, but which I rarely hear spoken of: Paul’s mysticism, which I suspect of being (or being derived from) Merkavah mysticism.

This Is Not That Prequel Miniseries

Unluckily, Merkavah (or Merkabah) mysticism is another topic that I can’t do justice to! This is because I simply don’t yet understand it very well; “but such as I have I give thee.”

Its name comes from the description given by Ezekiel of the divine throne or chariot (מֶרְכָּבָה [mer’kavah], “carriage, chariot”), which the angelic beings called Thrones accompany. Merkavah mysticism was the “standard” variety of Judaic mysticism during the Second Temple period (515 BC-70 CE). It continued producing new mystics and mystical works for centuries after the destruction of the Temple; I gather its most productive period was a little after the failure of the Bar Kokhba Revolt in the early second century, but some early Merkavah materials, and related Hekhalot literature,1 date to before the life of Christ. Both overlapped with the apocalyptic genre. The book of Enoch is probably the most famous example of Hekhalot literature, while the New Testament books of Hebrews and Revelation—both of which are concerned with a heavenly temple that is the archetype of which the terrestrial Temple was the ectype—both suggest influence from Merkavah mysticism and/or Hekhalot writings.

One thing a Merkavah adept might hope to do—and one he would know enough about to understand what was going on, if it happened to him or someone else—was to make what they called “the descent”:2 a journey into the heavenly palaces. There, if God favored them, they might receive the most sublime visions yet, or even converse with the Lord as when “the Lord spake unto Moses face to face, as a man speaketh unto his friend.”

The reason I’m so reticent about whether this was one of St. Paul’s personal ambitions is that, bluntly, I doubt he was such a fool. To phrase it lightly, the descent was not something one made a nice afternoon out of: it was a long, taxing, and indeed a dangerous endeavor; for “it is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.” There is a story preserved in the Talmud known as the Pardes legend, about four eminent scholars who accomplished the descent (pardes, “orchard,” is a term derived from Persian and related to the word “paradise”): Rabbis Akiva ben Joseph, Simeon ben Azzai, Simeon ben Zoma, and a fourth referred to only as Acher, “the Other One.” All four were surpassingly wise and virtuous; in fact, they were the only men of their age to fully grasp the mystical significance of the Torah. And of them, only one, R. Akiva, returned safely in body and soul. Ben Azzai died on beholding God; ben Zoma was driven mad; and “the Other One,” known to history as the apostate Elisha ben Abuyah, fell into idolatry in heaven itself.3

A depiction of one of the Thrones,4 dating

to the English Renaissance; note (the top of)

a set of scales in the Throne’s hand. Photo

by Martin Harris (CC BY-SA 4.0—source).

Principles: Translation Versus Hermeneutics

The handling of this passage is a little odd. English translations regularly make verse 7 the beginning of its own sentence, but in the Greek, it’s the final phrase of the sentence in verse 6, no two ways about it. This is why I’ve included verse 6 in my translation, even though it isn’t part of the Mass reading. (I distinguished it the way I’ve done for skipped verses elsewhere, printing the text that isn’t present in the lectionary reading in grey.) By a coincidence that just seems impossibly stupid, this small difference in verse divisions is what moved me to write the next several paragraphs here, detailing parts of how I approach my work. Originally, I put them to a footnote; however, the presuppositions we make about how translation is supposed to work are pretty important—and even I am embarrassed to need to distinguish paragraphs within a footnote—so I moved them up here.

What comes up here is the difference between translating a text on the one hand, and interpreting a text on the other. In substance, it’s the difference between telling people what it says, and explaining what it means. Those two things are closely related, and at times are inextricable, yet not always. It’ll be easiest to illustrate why by starting from the opposite extreme: one in which translation and interpretation are doing totally distinct things.

There’s a convention in anime shows that have romantic subplots, where one character will say this stock phrase to another: 月が綺麗ですね [tsuki ga kirei, desu ne]. The translation of this phrase is “The moon is beautiful, isn’t it”; which, okay, fine—except that isn’t the significance of the stock phrase. It became “stock” in the first place because it represents something else. The social norms of Japanese culture are highly motivated to avoid embarrassment, and therefore often classify direct speech about sensitive topics as distasteful. The upshot of all this is, the effective meaning of the stock phrase 月が綺麗ですね is “I love you.”

Now, if you look up 月が綺麗ですね in a dictionary, whether following the vocabulary by sound or the characters by scripts and radicals, none of it translates to “I,” “love,” or “you.” That’s because meaning never works that simply, in any human culture; it always operates on multiple planes simultaneously. To arrive at the correct, but exceedingly non-literal, interpretation of the Japanese, you have to know what cultural and contextual clues to follow.

A copy of a woodcarving from 1475

depicting the “seven heavens” (or nine,

if the sphere of the fixed stars

and the Empyrean are counted).

This is obviously not a new problem! But it bothers me, because it’s in tension with the philosophy of translation I prefer. This philosophy is that I, as a translator, should interpose myself between the reader and the text itself as little as possible. I’m at liberty to offer commentary on the text as well as translate, and I do; but the two activities need to be very clearly distinguished from each other, both to me and to the reader. There are a few reasons for this, but the biggest one is, I have no right to arrogate Scriptural authority to my opinions!

This is what leads me, first, to my appetite for literalism; and then immediately to my next-highest desire, to be idiomatic: both are versions of the desire for maximum clarity, for the text and not me to speak. (Or rather, for the text to speak and, if I speak at all, for me to speak distinctly from it.) The problem is, while I think these two desires—literal translation and idiomatic translation—are less in conflict than many translators make them out to be, it is nearly always true that they can’t both be equally satisfied. Occasionally, one of them has to be sacrificed entirely to get a text in readable English.

Idiom, Æsthetics, and Vocabulary

Overall, I’d say that if my translation in this post has a weakness, it’s that it doesn’t sound as pretty as alternatives like the RSV’s; that’s a real shame, because I find Paul’s variety of elegance particularly winsome. However, there’s only one book of the Bible in which I believe that æsthetic considerations ought to enjoy a casting vote; and II Corinthians is not a Psalm, so too bad for me.

Lastly, I think I’ve talked about the following stuff before, but I’m not sure I’ve ever given a full explanation. When translating, I try to avoid what are sometimes called “Greeklish” words—apostle, canon, presbyter, etc.—and replace them with more-familiar English equivalents such as “envoy,” “rule,” or “elder.” This in itself is not very unusual, but I carry the principle a lot further than most translators of the New Testament, even excising words like angel and Christ in favor of “messenger” and “Anointed.”

I wish to emphasize, this is not because I think they have “been mistranslated.” They haven’t; as a matter of fact, I will citizen’s-arrest the first person who so much as thinks the phrase “a game of telephone” while reading this post. Moreover, the concepts represented by our “Greeklish” words are plenty distinctive enough to merit our having specialized terms for them. Especially given those ideas came to us from Greek, there’s absolutely no reason we shouldn’t have, keep, and use such words, speaking in general. The reason I steer away from them in this context is that I’m trying to make the text as it then was to its first readers maximally accessible; to them, these bits of “Greenglish” were still just ordinary words, so that’s how I want them to hit here. That is the ideal description, of course, from which any execution will fall short, but that is the ideal I’m falling short of when I do so.

II Corinthians 12.6, 7-10, RSV-CE

Though if I wish to boast, I shall not be a fool,a for I shall be speaking the truth. But I refrain from it, so that no one may think more of me than he sees in me or hears from me. And to keep me from being too elatedc by the abundance of revelations,b a thornd was given me in the flesh, a messenger of Satan,e to harassf me, to keep me from being too elated. Three times I besought the Lord about this, that it should leave me; but he said to me, “My grace is sufficientg for you, for my power is made perfecth in weakness.” I will all the more gladly boast of my weaknesses, that the power of Christ may rest uponi me. For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults,j hardships, persecutions, and calamities; for when I am weak, then I am strong.k

II Corinthians 12.6, 7-10, my translation

For even if I do want to brag, I will not be senseless,a for I am telling the truth: yet I spare it, lest anyone reckon me above whatever they see or hear from me, in superiority from the revelations.b So that I would not be exaltedc on their account, there was given to me a spiked in my flesh, a messenger from Satan,e so that it should beatf me, so that I would not be exalted. About this, three times, I appealed to the Lord that it be sent away from me; yet he told me: “My grace sufficesg you; for power is finishedh in weakness.” Most gladly, then, I will brag instead about my weaknesses, so that the power of the Anointed may quarter withi me. Because of this, I am pleased with weaknesses, insults,j needs, persecutions, and distresses, over the Anointed; for whenever I am weak, then I am powerful.k

Russian ikon of St. Paul the Apostle

(love you St. Paul, and I did put the

picture of Jesus first, but I didn’t

promise not to have one of you in).

Textual Notes

a. a fool/senseless: This word (ἄφρων [afrōn], for those of you scoring at home) is quite interesting from a strictly linguistic point of view. The virtue of temperance or moderation was referred to in Greek by the related name σωφροσύνη [sōfrosünē], literally “sound-of-mind-ness”—sanity, or even sobriety, would be reasonably good modernizations. Both terms derive from a word that goes back to the Homeric era, and indeed to proto-Indo-European: φρήν [frēn], which probably meant “midriff” or “heart, breast”; and yes, the term “phrenology” has just hoved into view, but as it’s entirely too silly, I’m having that one hoven back. (What may look like an e/o discrepancy between derivatives of this root is actually a familiar feature of proto-Indo-European grammar.)

As for its meaning, the word kind of boxed the compass, between the time when Homer was (reputedly) barding his φρήν out and the time when St. Paul disclosed his to Corinth. At different periods, it could denote the seat of your appetites, your intellect, your emotions, your will—basically, the border of its meaning amounted to “that which prompts behavior.”

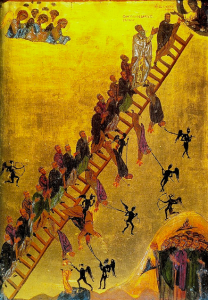

The Ladder of Divine Ascent, a celebrated

ikon from St. Catherine’s Monastery

on Mount Sinai, Egypt.

However! All of this is merely interesting detail that lends a little color to translating ἄφρων (i.e., being without φρήν or lacking φρήν) as “senseless.”

b. the abundance of revelations/in superiority by the revelations: As I’ve said, I prefer to keep my role as an interpreter of the text to a minimum; however, occasionally it can’t be avoided, and that seems to apply in this case. The wording, thankfully, is not at stake: τῇ ὑπερβολῇ τῶν ἀποκαλύψεων [tē hüperbolē tōn apokalüpseōn], translated literally, is “the excess of the revelations.” (Neither the RSV nor my translation actually use “excess” to translate ὑπερβολή, so, to limit confusion, I’m going to do the pastor-fresh-out-of-seminary thing and use the Greek word in the rest of this note.)

The point of contention is what meaning ὑπερβολή bears in this context. It’s in what’s called the dative case, which has a few different functions. The RSV interprets this as a dative of agency, expressing the agent of a verb; this kind of dative is normal with verbs in the middle or passive voices—see note c below for more on the middle voice. On this showing, ὑπερβολή is the thing-by-which the “elation” would be happening (if St. Paul were elated).

However, as far as I can tell, the dative-of-agent interpretation is based on the quite separate idea that this phrase goes with the rest of verse 7—which it doesn’t; it’s the last phrase of the sentence in verse 6. Accordingly, I take this to be a dative of circumstance, describing conditions that attend some event. In this case, the event is hypothetical: if (counterfactually) St. Paul did not spare us his bragging, then people might easily believe that he is in a state of ὑπερβολή, compared to the rest of the faithful. This is where I felt the double meaning of “superiority” served the text fairly well: a word like superior can be strictly descriptive in English (as when one “reports to one’s superiors” in a business or an army), but it can also be an unflattering claim about how they view themselves (as when a person “acts superior”).

I’m having flashbacks to College Park now.

I wrote a bit there saying that, like its verbs,

Greek pupils have moods: Bad, and Worse.

Photo: Radhika Kshirsagar, CC BY-SA 4.0.

c. too elated/exalted: This verb, though a pretty simple one in Greek, defies simple explanation in English. The root of the term is a simple verb meaning “to lift” or “raise.” The preposition ὑπέρ [hüper] is then stuck on the front, which is related to the Latin super and, more distantly, the English word “over,” all three of which have the same meaning (and yes, this is where we get the prefix hyper-). The verb is then put into what’s called the middle voice, which covers verbs that don’t neatly fit into the categories of active and passive5; to generalize, it covers actions that are done to oneself (or reflexives), and also those done to one’s own benefit (or detriment—grammatically, it makes no difference).6 All told, then, we have a verb that, hyper-literally and with the adverbs, means something like “lest I lift myself up above” or “lest I lift myself on high”; the object of “other people” is implied.

d. thorn/spike: I was prepared to learn that “thorn” wasn’t an accurate rendering, especially since the word here, σκόλοψ [skolops], is used in modern Greek for “scalpel,” if memory serves. I was not prepared to learn that its real meanings include not only “hook” (as in a fishhook—specifically the point, as distinct from the curved bit which hook is more associated with in English), but also “a tool for operating on the urethra.” In fact, I don’t know what could prepare a person to learn that; and that is why I didn’t prepare you, dear reader!

e. a messenger of Satan: You’ll also see this rendered, a little less literally, as “an angel of Satan.” A few people have interpreted this as meaning that St. Paul was demon-possessed; given that, to the best of my knowledge, no other sources (either biblical or sub-apostolic) hint at this—I don’t think even Paul’s enemies charge him with such a thing—I find this interpretation extraordinarily unlikely.

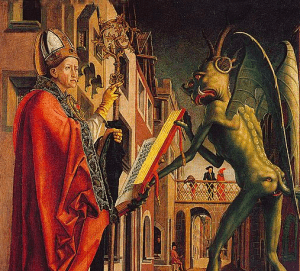

A Difference Over Augustine, by 15th-

century Austrian artist Michael Pacher.

It really, really should bother me that this

image is so frequently apt. Right?

More plausible, in my opinion, is the theory that St. Paul had epilepsy. Epilepsy was widely known as “the sacred disease” in ancient times, and attributed by most people to evil spirits, though some at least among the educated were asserting that it was properly a disease, i.e. of natural origin, as early as Hippocrates. This explanation allows St. Paul’s “messenger of Satan” to be literal, metaphoric, or both at once, and seems to me to track with his other vague references to his “affliction.” Furthermore, while this isn’t universal, epileptic seizures can be accompanied by visual hallucinations, and are sometimes followed by blindness or blurred vision (which is normally but not always transient), matching the handful of more specific allusion to something being the matter with his eyes.

The big weakness I see in this theory is, if Paul did have anything in the nature of seizures or fits, he would probably have been widely reputed to be possessed (which again raises the problem of silence even from his enemies). Doubtless, the testimony of the apostles would have done something for him under such circumstances, but I’m not sure how much—and anyway, it would only have done so among people who were already Christians, not among the vast majority of the people he went to on his missionary journeys. I should also point out, though it does not in itself discredit the theory, that some people who subscribe to it do so to explain away his visions and locutions in general, as mere epileptic symptoms that affected the temporal lobe of his brain. (The temporal lobe handles both sensory input and language processing, among other things, so you really don’t want things affecting that lobe all willy-nilly.)

Demon possession and epilepsy aside, St. Paul’s “spike” could have been practically anything. And I suppose, considering he didn’t choose to tell us what it was more specifically, it isn’t really our business.

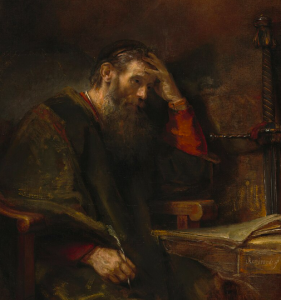

The Apostle Paul, c. 1657, by Rembrandt.

f. harass/beat: “Buffet” (the one that rhymes with “stuff it,” not with “delay”) is another old favorite for this word. English, perhaps disquietingly, has developed a lot of fine distinctions in its terms for knocking people about; Greek assigns “beat,” “punch” or “box,” “smack” or “slap,” and metaphorical or generalized meanings like “torment” or “mistreat,” all as gradations of meaning common to the one word κολαφίζω [kolafizō]. Shows what they knew.

g. is sufficient for/suffices: Alternate translations of this verb include “to assist” and “to ward off.” However, the latter doesn’t really make sense here, and the former is—forgive me another lapse into subjective evaluation—such a bland message as hardly to seem worthy of Paul or Jesus. That grace helps, the apostle doubtless knew already; whether it was enough was, apparently, a question of actual moment at the time.

h. is made perfect/is finished: A little like the verb from note c above, this one isn’t difficult in itself, but it is tricky to render—not in the sense that you’re likely to wind up with a wrong translation if you know even the basics of Greek, just that there are nuances you’d be forced to leave out. The verb is τελεῖται [teleitai]; it is related to the τέλος [telos] or “goal, purpose” that we know from philosophy, and also to the sixth of the seven sayings from the Cross, τετέλεσται [tetelestai] or “It is finished.” The sense of the text could thus be taken as “power ends in weakness” (i.e. every human power fails eventually) or “power is made complete in weakness” (i.e. the most complete kind of power is the one that can exert itself even in the midst of weakness) or “the end of power is weakness” (i.e. Christ’s power exists to serve weakness), and perhaps other meanings besides.

The “Canterbury cross”: a 9th-cent. bronze

Saxon brooch. Its unique shape has come to

symbolize English Christianity. Photo by

Storye Book (CC BY-SA 2.5 license: source).

For lack of a better way to put it, the RSV’s “perfect” here (inherited from the King James) ought to be a good translation; it still was as late as the nineteenth century, possibly into the early twentieth.7 This is because the root of the English adjective “perfect” is the Latin verb perficere: “to complete, carry out, finish.” Unfortunately, due to semantic drift, the perficere-sense of the adjective ceased to be its most familiar and least context-conditioned meaning a long time ago, and was replaced by a related, logically close, but different sense: “flawless, ideal, best possible.” Accordingly, it does one of the most irritating things a word can possibly do: take the reader’s mind to an idea that’s also true, but the wrong one here. Getting readers even to notice what’s gone wrong is nearly as hard as noticing it yourself as the author. In my experience, this kind of subtle misdirection is reparable only by excising the offending word bodily and starting over afresh, even at the price of recasting the whole sentence.

i. rest upon/quarter with: It would not be true to say that most, or even many, of the problems I’ve face in my life have been related to the Greek word for “tent”; I can think of maybe two, but what I couldn’t think of was a more compelling way to open this paragraph.

Anyway, ἐπισκηνόω [episkēnoō] can be translated as “rest upon” without doing violence to the language, though, given this is one of the assorted derivates of σκηνή [skēnē], “tent,” I wish the RSV’s translators had made at least a token effort to get that idea into the word they chose. It would be natural to render this verb as “set up camp at,” for example; this is doubtless how it came to be applied to armies regularly. And, being so close after the Fourth of July, I couldn’t resist the specific Bill-of-Rights nod in describing divine grace as “quartering with” the apostle.

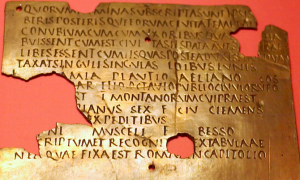

The remains of an honorable discharge from

the Roman army (in Latin, a diploma),

unearthed in modern Austria. Photo by

Matthias Kabel (CC BY-SA 3.0 license: source).

j. insults: This word is actually our old literary friend, ὕβρις [hübris]! We’re used to thinking of it as an elevated synonym for “pride,” and that’s not inaccurate. However, a word like “insolence” suits it better: it conveys overt and unearned disrespect toward others (especially impiety), not merely being conceited in public.

k. strong/powerful: Here we again have a “not hard, but frustrating” word—the adjective δυνατός [dünatos]. It is perfectly logical that the verb meaning “to be able to; can” is related to the noun for “power” and the adjective “powerful, able.” There’s nothing wrong with occasionally replacing “I am able to” with “I have the power to” in English. But your English is going to look weird if you say “have/has the power to” every time a normal person would say “can,” while on the other hand, I don’t know if there even is an English noun or adjective related to the word “can” that would serve as synonyms for “power” or “powerful,” respectively. Irksome.

In translating δυνατός, however, “strong” strikes me as slightly off, on strictly linguistic grounds. (On æsthetic grounds, I think it’s much better than my choice; we don’t have a conventional antonym pair in weak vs. powerful: it’s weak vs. strong that feels like an obvious set, and therefore “sounds better” in a sentence.) A more usual word for “strong” would be κρατύς [kratüs]. Of course St. Paul isn’t talking in a “feats of strength” sense (though κρατύς could be used metaphorically); but I wonder if part of the reason δυνατός appears here is that the noun δύναμις [dünamis] or “power” is sometimes used to refer to miracles.

The Conversion of St. Paul (1600), Caravaggio.

Footnotes

1I’m still not sufficiently familiar with either field of literature to say this with any confidence, but I have the impression that Hekhalot (“palaces”) literature tends to stand in relation to Merkavah literature proper in kind of the same relationship the (orthodox) infancy gospels have to the canonical four. In other words, they are broadly “about the same stuff,” and make the same assumptions about that stuff, but that they are not—and are often not attempting to be—accounts set down by visionaries of their experiences; they might aim to offer pious entertainment, rebut skeptics, or even excite religious devotion, but they would not be “technical” in the sense of containing real instruction on how to enter a trance, for example.

2We of course would have expected the word ascent here, given that the God of Israel is very much a God who resides up in the sky (however poetically we take that). My hunch about this idiom of “descent” is that it represents something like “going in,” rather than “going down.” However, it’s at least equally possible that “descent” instead of “ascent” was a reverent euphemism, such as we might expect to occur in discourse on what was considered a highly sensitive, indeed a dangerous, subject.

3The exact nature of Elisha ben Abuah’s heresy is a matter on which the Talmud is tight-lipped. In one elaborated version of the story, it is said he saw the Metatron (the traditional name or title for the angel who is the Lord’s mouthpiece), seated, in the divine throne room—sitting down is something only the Lord himself is understood to do there—and concluded that “there are two powers in heaven”: in other words, he became a polytheist. It is not clear whether this means ben Abuyah pursued some kind of heterodox Judaism of his own devising, or converted to Christianity (whose doctrines of the Trinity and the nature of the Torah were abominated by mainstream Judaism), or became something else entirely.

4This humanoid portrait is kind of an unusual way of depicting one of the Thrones. It was commoner in the Middle Ages; this illustration comes from the rood screen of a church in Norfolk, England. Modern depictions mostly go for the bizarre, sometimes far in excess of anything that could correctly be called “biblically accurate angels.” Conversely, the most remote ancient literature believed to give an account of the Thrones is Ezekiel itself, principally in chapter 1 and, with minor variations, in chapter 10. They are widely identified with Ezekiel’s ophanim or “wheels.” These ophanim are rather confusingly described, and bear an unclear relationship to the tetramorphs (the four-faced creatures combining elements of men, lions, oxen, and eagles); the wheels and the tetramorphs might be distinct parts of the same being, or two different beings that move together. Physically, the ophanim sound more like gigantic gemstones than anything else; they are explicitly compared to a kind of semiprecious stone, although unfortunately we don’t really know what kind, as ancient Hebrew mineralogy is rather poorly understood.

5To fellow Classicists, grammarians, etc.: I’m sorry, come at me, but we don’t have time. Look at how long some of these footnotes are, it’s obscene. So we’re not doing deponents, and we’re not doing the subjunctive mood, and we’re not doing whatever bespoke version of reflexive pronouns you were about to point out doesn’t align with the strictly practical and abbreviated summary below.

6An example of an English verb which Greek might use the middle voice to convey is “cooked” in Mary cooked herself some dinner. This is an active-voice verb in English; it contains a reflexive pronoun (all7 pronouns ending in –self or –selves are reflexives), but the verb is not reflexive. If it were, “herself” would be the direct object, and this is no time to start discussing the Donner Party. Mary is both the subject of the verb and its indirect object (the dinner is for her), a construction that falls quite neatly into the middle voice; if she had instead cooked John some dinner, it would be a straightforward active verb like in English.

7I produce even this vague period with some diffidence. By the time Dorothy Sayers—a person abnormally sensitive to the finest shades of meaning in language, by both temperament and profession—first published Creed or Chaos? in 1940, she had observed the semantic drift in question at the popular level; we know this, because she made suggestions in that book about how to meet the challenge that this drift in the meaning of “perfect” cast before the Church. I imagine she was both more exposed than most professional academics to this kind of linguistic change, and also more interested in and attentive to it, given she was a respected novelist working in a contemporary and very popular genre. If a minimum of one novelist had had time to both observe and reflect on this shift in meaning, I assume it can’t have been less than a few years old by that point (most semantic shifts only become clear in retrospect). Let’s say the word’s “center of gravity” changed no later than 1920, so that by 1940, we’ve got an entire cohort of just-come-of-age adults who’ve spent their entire lives using “perfect” with the flawless-sense as its default meaning, rather than with the perficere-sense. That seems to me like it would lead to enough small, but detectable, misunderstandings in reading and conversation to prompt an unusually sensitive person, like Miss Sayers, to realize what had happened. This would indeed give us a date not later than the early twentieth century, making the late nineteenth quite possible.

Having finished (or, if you will, perfected) this paragraph, it has come strongly into my mind that nobody but me is likely to care about it even a little bit. That said, if you read this paragraph on one of my severely niche interests and liked it, then there are at least two of us who are Like This!