Back in 2015, I published my first novel, Death’s Dream Kingdom. I am currently working on a sequel, The Book of Salt, which is set in London in 1888, the year of the Ripper. This is an excerpt from that book. Enjoy!

For somewhere in that sacred island dwelt

A nymph to whom all hoofèd satyrs knelt,

At whose white feet the languid tritons poured

Pearls, while on land they withered and adored.

—John Keats, Lamia

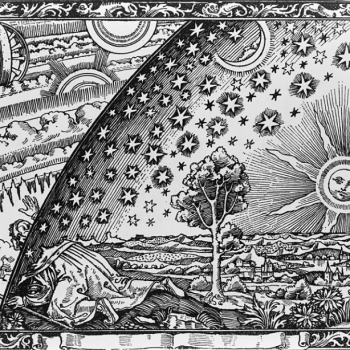

It was the twenty-third of July, and night lay thick on the streets and alleys of Whitechapel. A lunar eclipse was beginning; the Moon was a well-polished copper. A man in his middle forties moved cautiously through the streets, hand hovering over a small phial full of holy water that was fastened at his waist, like the pistol of some American outlaw. The beads of a rosary dangled from his other hip, and behind that was strapped a long, smooth spike of hazel wood, which had been soaked in sacramental oil. Hillyard had nothing to fear as long as he was vigilant.

A soft scuffling met his ears, and he swept round to meet his foe, stake instantly in hand.

The small, semi-tame rat that he had heard nosing around in the stacked milk crates to his right sniffed gently at the sharpened end of the stake, then scurried off along one of the alley’s ill-defined gutters. The man exhaled, and in so doing realized that he had been holding his breath. He smiled ruefully at himself.

Before he had altogether collected his wits, a crimson shadow lunged out of the mouth of a side street. He swung his phial wildly. There was a cry of pain and a sickening crunch as he made contact with his assailant’s skull, and a wet sensation crept through his fingers and over his skin. He drew breath through clenched teeth.

A groaning, oddly familiar voice sounded. ‘Bloody hell. Hillyard?’

‘De Vine? Is that you?’

It was indeed that dark and lithe young man. The pair disentangled from each other, tugging smartly at their jackets and trousers as they composed themselves. ‘You gave me quite a turn,’ said de Vine, putting a hand gingerly to his own wounded scalp. ‘I say—your hand is bleeding, mate. Must’ve cut it on the glass when you broke your phial. Here.’ He pulled a shabby but clean handkerchief from one of his pockets and wrapped up Hillyard’s cut hand, securing it with a tightly-knotted piece of string. ‘I expect I’ve got a nasty something-or-other on my head as well, eh?’

‘It isn’t so bad,’ Hillyard said, studying it carefully. ‘Head wounds bleed perfectly pig-like, but it’s got no glass in, thank God. You might go back to Saint John’s and have Father have a look anyway.’

‘He won’t be up for the dawn Mass for three-quarters of an hour yet,’ de Vine objected, pulling out a second and still shabbier handkerchief. ‘I might as well finish the patrol.’

‘What, with a bloody patch on the side of your head so they can smell you the easier?’ scoffed the other. ‘To say nothing of losing one hand because you have to hold that rag on it. Go on, de Vine, I don’t mind finishing up alone. They’ve hardly troubled Whitechapel anyway, it’s pure routine.’

‘Alright. Just be careful.’ De Vine clapped his free hand on his companion’s shoulder, and they parted ways. Hillyard crept north along Brick Lane, the faint, reddish Moon glowering above him. It was as he drew close to the Truman Brewery that he heard the singing.

A pure, piercing soprano voice was floating through the air. It sang in French, which Hillyard did not speak, but it sounded sweet and intricate and potent, like a hero’s lover from an opera. A white shape appeared in a parallel street, walking in the other direction—the voice’s owner. It was a young woman, extraordinarily fair of skin but with rich black curls, tied back from her face with what appeared to be a thick white ribbon. She was clad in a shimmering gown and long pearl-button gloves, a gauzy shawl around her naked shoulders; her mouth showed brightly against her skin, scarlet on ivory. She darted a brief glance in Hillyard’s direction, and continued to walk and sing.

‘Er … miss? Madam? Hullo there!’ he called, and began to follow her. It wasn’t safe or proper for a young lady, especially one as obviously well-to-do as herself, to be walking the filthy back-alleys of Whitechapel at this time of night. But she took no notice of him, and when he had reached the road she was walking down, he found himself much further behind her than he had thought—yet she was walking slowly, even languidly. He hurried to catch her up. She turned a corner to the left; once again, when he reached the spot and made the turn himself, the young lady was far further along the street than she ought to have been. Ordinarily this would have aroused the suspicion of a man with Hillyard’s years of experience, but his mind was strangely clouded.

She led him for some time on a tour of the east end, the alleyways tangling with themselves like knotted hairs. Above them, the eclipse proceeded apace, souring the moonlight to a dark rust-red. At last, secreted away in the worst passages of Whitechapel, she stopped at the end of a blind alley. It hooked away from its mouth onto the main street: no one could see what might happen in its cul-de-sac.

‘Madam?’ said Hillyard again. ‘I do beg your pardon for following you, it’s only that you seemed lost, and, er, I tried to get your attention but you didn’t seem to hear me, and—’

‘That’s quite alright. I understand completely,’ she said to him without turning around.

‘Haven’t you anything to keep warm? Are you out here alone?’

‘You are here,’ she replied.

‘Well, that covers the one but not the other, so to speak, madam.’

‘So to speak.’ She laughed softly.

Hillyard took an uncertain step closer. ‘May I offer to chaperone you home?’

‘Are you hunting vampires?’ she asked, conversationally, as if it were a remark as ordinary as observing the weather.

‘What? No. Don’t be absurd—I beg your pardon, madam, I don’t mean to be rude, it’s only …’

‘I think you are,’ she said lightly. ‘At any rate, it’s difficult to see why a solicitor’s assistant should be lugging around holy water and a rosary and a hazel stake in the middle of the night; any two of those without the third might admit of an innocent explanation, but the full trinity rather looks like a confession. Good luck getting that stake through an opponent’s ribcage on the first try, by the way, especially if she is wearing a corset. Ten to one odds you’ll just about manage to break the tip off in her flesh, without penetrating her deeply enough, leaving you a bloody, weaponless mess.’

The woman swept around, and her eyes bore into his. Hillyard had a horrible cold sensation that she was seeing right into the depths of his mind and didn’t think much of what she saw. ‘You should have stayed away,’ she whispered angrily. She reached up to the ribbon that was holding her hair back, and it turned out to be securing something else as well. She shook out a finely woven expanse of white linen—a veil. It floated downwards, falling from the crown of her head to obscure almost her whole face, except the poisonous red mouth. Hillyard’s vision was beginning to swim. She extended her hand to him in a commanding gesture.

He opened his mouth, and felt his fingers loosen. There was a clattering noise; if Hillyard had looked down, he would have seen his stake, fallen uselessly to the cobblestones. He struggled to form words. Her face was much closer than it ought to be; he could make out her eyes through the veil; they were violet.

‘Who are you?’

She laid a soft, intimate hand on his wrist and gently pulled him in. ‘I am the Lamia.’