Go here for Part I and Part II.

Repenting of centuries of racism and genocide is not an easy thing to do. Part of the problem is that it’s kind of vague; another is that the things we usually think of here, like the trans-Atlantic slave trade, are far enough in the past that it’s difficult to connect with them on an emotional level. They not only aren’t things we personally did, they aren’t things our grandparents did. Repentance is easier—and harder—when we can focus on something concrete.

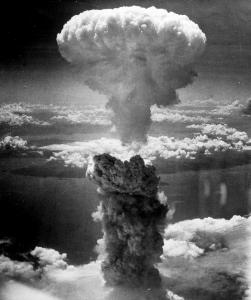

Seventy-six years ago, we gave ourselves something very concrete to repent of as a nation. Namely, in a matter of seconds, we obliterated two cities, full of unarmed civilians of both sexes, from the unborn baby to the octogenarian.

The Bombings Were Sins

It still surprises me a little that so many Catholics in this country are fine with what the US did at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Part of it’s misinformation, to be sure. For instance, only a few years ago a saw a pious person circulating a nice story about the bombing of Nagasaki in particular; it’s been the center of Japanese Catholicism for hundreds of years, and the bomb hit the ground less than half a mile from Urakami Cathedral. The story stated, correctly, that the cathedral was full, even though it was a weekday—people were getting ready for Assumption in a week and a half. It also said that the people in the cathedral remained safe, hinting that this was a miracle. This is a comforting lie. What actually happened is that the cathedral was destroyed and everyone inside was killed.

What’s surprising is that so many Catholics casually accept these acts, when the bombings are such obvious, textbook violations of the Church’s teaching about justice in war. Some passages in the Catechism read like they were written at the US:

The strict conditions for legitimate defense by military force require rigorous consideration. The gravity of such a decision makes it subject to rigorous conditions of moral legitimacy. … [T]he use of arms must not produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated. The power of modern means of destruction weighs very heavily in evaluating this condition. … Non-combatants, wounded soldiers, and prisoners must be respected and treated humanely. Actions deliberately contrary to the law of nations and to its universal principles are crimes, as are the orders that command such actions. … “Every act of war directed to the indiscriminate destruction of whole cities or vast areas with their inhabitants is a crime against God and man, which merits firm and unequivocal condemnation.”1

There’s no ambiguity here. There are no mitigating factors or technical exceptions. It should not be difficult for any Catholic to grasp the implications of this teaching.

The Rationalizations Are Crap

For a Catholic who believes that the Church is the bearer of divine revelation, that should settle the matter. But Americans, papist or not, really don’t like admitting that our country has ever done anything bad. We’re the good guys. So if we did this it must have been good somehow.

The most common justification for the bombings is that it saved lives by ending the war faster. But that’s really not an argument for any act of war; what it’s an argument for is immediate ceasefire on any terms whatever. That really does stop people from killing each other, and it even does it without killing tens of thousands of people and giving the rest radiation poisoning.

Wreckage of Urakami Cathedral

Then there’s the claim that Japan would never have surrendered, that they would have fought literally to the last man, woman, and child. Setting aside the fact that that’s brain-meltingly unlikely (I’m aware that child soldiers are a thing, but the idea that you could have an entire nation with zero non-soldier children makes me skeptical), the Japanese were probably going to surrender anyway. Their only real ally had been punched in the face so hard the fist came out the back of their skull, and the Soviet Union had just declared war on them, something they’d been counting on avoiding. Contemptible lib-cucks like MacArthur and Eisenhower said, both at the time and afterwards, that the bombings were totally unnecessary. If anything, the Allied insistence on an unconditional surrender from Japan (itself a needlessly humiliating demand that complicated the whole process) prolonged the war more than Japanese stubbornness did.

A lot of people try to bring in Japanese war crimes at this point, as if they have anything to do with this. There isn’t a threshold of awfulness past which it’s okay to do war crimes on them; there isn’t even a threshold of the other guy doing war crimes past which it’s okay. That’s not how evil works.

The Point

Okay, but so what? Am I trying to make people feel guilty about heroizing their granddads or something? Feeling bad about Hiroshima and Nagasaki isn’t going to bring anybody back from the dead.

Of course not. And I’m sure your granddad was a lovely man, but that’s really not what this is about. To approve of an evil act is, itself, evil. It both comes from and causes a warped idea of right and wrong. For Catholics, that is and should be a really big deal.

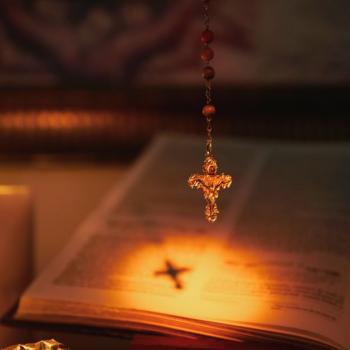

What’s more, Catholics do believe we can do something about the tragedies of history; that’s what the atonement is. We offer reparations in the form of fasts and holy hours and rosaries and so on, because we trust that God, in a mysterious way we rarely understand, will use those things to heal the damage done in the world by evil. Feeling vaguely guilty doesn’t do much good, no; but if we take that opportunity to do penance, we can help bring Christ into those torn-up places.

1Catechism of the Catholic Church §§2309, 2313-2314. The quotation is from Gaudium et Spes, the pastoral constitution on the Church in the modern world from the Second Vatican Council, composed less than twenty years after the atomic bombs were dropped.