The other day I came across a wonderful little essay “The Minimum Working Hypothesis,” It was Aldous Huxley’s attempt at providing a core to his belief in a perennial wisdom. It triggered a wave of thoughts for me. And in particular how much I owe to him and two of his colleagues Gerald Heard and Christopher Isherwood. One more distantly, but two inescapably.

It inspired me to pause and gather a few thoughts about these three people and the threads that came together to inform me at the beginning of my adult life. More actually, as I was beginning to think of having an adult life.

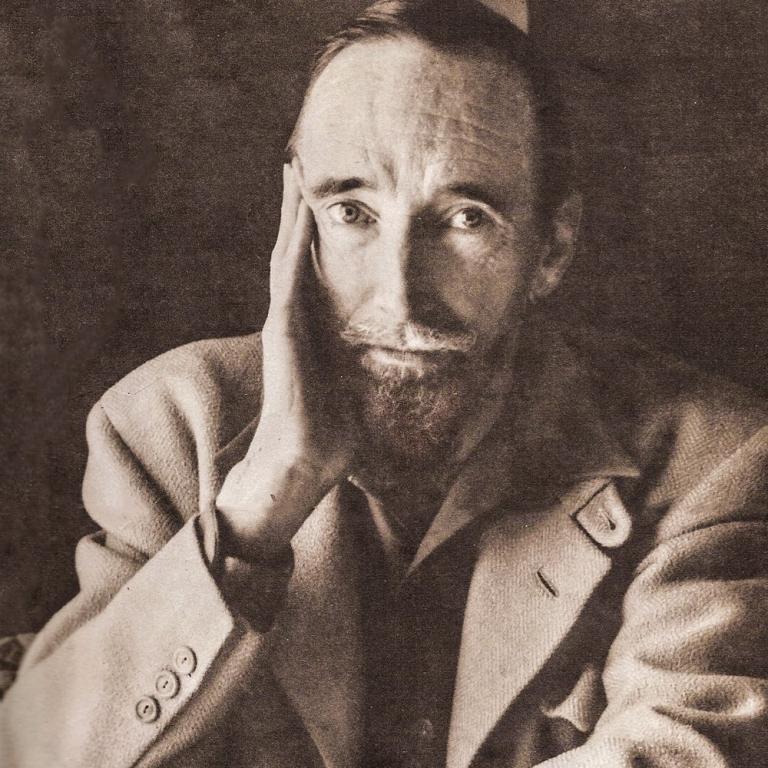

Henry Fitzgerald Heard was born in 1889, the son of an Anglican priest. He graduated from Cambridge University, and then taught briefly at Oxford.

He was first known in the 1930s as a popular science commentator on the BBC. He was widely admired, although some saw the very range of his interests reduced him to gadfly status. Ultimately he wrote thirty-five books ranging from mysteries, to science fiction, to science, philosophy, history, and religion.

Heard was deeply interested in the conflict between human advances in technology while remaining stagnant or worse regarding the spiritual and psychological life. He believed there was an evolutionary spiritual movement connected to mysticism. Although, as he saw it, this positive direction was constantly stymied by this imbalance, where humanity over focused on individuation to the detriment of our sense of interdependence, wonder, curiosity, and love.

He emigrated to Los Angeles in 1937. His longtime friend Aldous Huxley accompanied him. Noting the physical similarities between Southern California and the ancient Near East, he reveled in both the prevalence of crank religions and it being the meeting place of authentic traditions gathering from east and west. It was there that he met the remarkable Swami Prabhavananda, a monk of the Ramakrishna Order and minister of the Vedanta Society of Southern California. The swami founded monasteries and convents in Hollywood, Santa Barbara, and Trabuco Canyon.

As I think of it, the swami is a fourth figure in my spiritual formation. I met him mainly through his translation work with Isherwood. That and through Isherwood’s memoir My Guru and His Disciple. And, well, through his imprint on all three I’m writing about here…

In 1943 Heard purchased property in Trabuco Canyon in Orange County, where with Aldous Huxley he established his Trabuco College. It was a retreat center for the just beginning Human Potential Movement and is generally credited as the pattern for Esalen Institute. Heard envisioned it as a sort of semi-monastery, where he would mentor a new class of neo-brahmins, spiritual leaders for a new age.

(Hearld-Examiner)

Heard was for a substantial period of time a successful public speaker and writer. Those thirty-five books. His later years were devoted to experimental psychotherapy, the rising psychedelic movement, and parapsychology. He was a popular early presenter at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur when it was opened. His core message that there was an emerging universal religion that synthesized the wisdom of east and west.

While once widely known, his star has faded. The college would pass on to the Vedanta Society as the nucleus for a monastery.

This said, his importance to Huxley and to Isherwood is hard to calculate, but was substantial.

Personally, I was never attracted to his writings. Well, except for the three novels beginning with A Taste for Honey, featuring a Mr Mycroft, who might or might not be Sherlock Holmes.

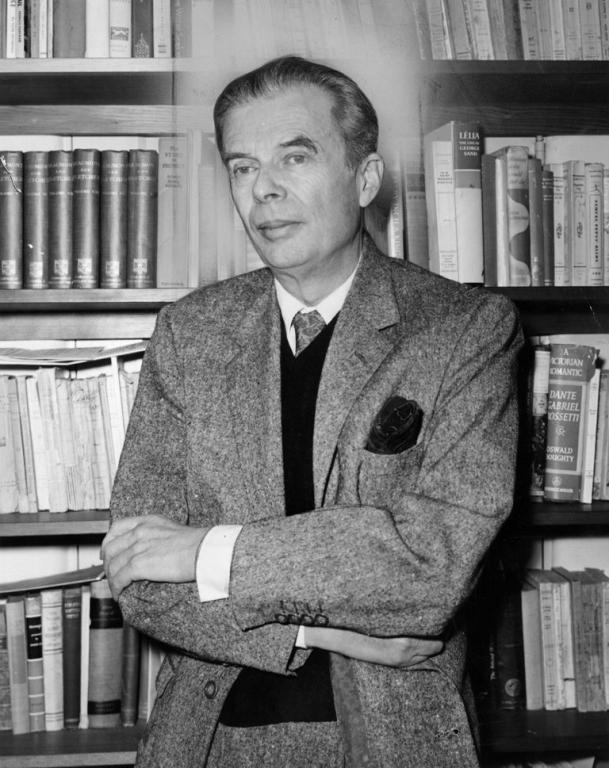

Aldous Leonard Huxley was born to English intellectual royalty in 1894. He was the third child of the writer Leonard Huxley and Julia Arnold, the niece of Mathew Arnold. His grandfather was Thomas Huxley, “Darwin’s Bulldog.” Aldous was named by his mother for a character in one of her sister’s novels. He earned his degree at Oxford. During the first world war he was rejected by the army because of his poor eyesight.

Huxley achieved fame as the author of satiric novels through the 1920s and the very beginning of the 1930s. In my late teens I read many of these novels, starting with Chrome Yellow.

While in England, through Heard’s influence, Huxley embraced pacifism. In the interwar period he was embroiled in the practical questions of pacifism, and his thinking continued to evolve a social and spiritual sense. As the gathering clouds of war began to overtake the 1930s, he found himself increasingly isolated in England. And he followed Heard to America in 1937.

My own intellectual and spiritual life would be touched by two nonfiction books of his, one written just before the war, Grey Eminence, a spiritual and political biography. The other not too many years after, The Devils of Loudin, touching on the dangers inherent in self-absorption. Although I have to admit at this point my memories of it are visual, pretty much of the movie rather than the book I read. That said what one can call warnings about the spiritual life woven through these two books found a place in my heart.

Of course, it’s his 1945 book, the Perennial Philosophy that has proven the most important to me over the years. The core thesis is that the purpose of our lives is to find the “immanent and transcendent Ground of all being.” As he says in his introduction,

“Rudiments of the Perennial Philosophy may be found among the traditionary lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions. A version of this Highest Common Factor in all preceding and subsequent theologies was first committed to writing more than twenty-five centuries ago, and since that time the inexhaustible theme has been treated again and again, from the standpoint of every religious tradition and in all the principal languages of Asia and Europe.”

In essence he illustrates a relatively simple thesis with a wonderful collection of quotations from the world’s religious literature. Part of its charm is that he preferred lesser-known quotes to the tried and true of comparative spiritualities. Not a scholarly book, and lacking citations that I wish for, it is nonetheless something of a handbook of the universalist spiritual life.

It was condemned and it was praised. Over the years I believe his Perennial Philosophy has only been outsold by Brave New World.

I’m grateful that it fell into my hands at a right moment.

The third party of this literary and spiritual trinity is Christopher Isherwood.

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood was born in 1904. The family was monied. He attended Cambridge, but his satirical writings led him to be invited to leave without a degree. He also spent six months a King’s College.

His first novel was published in 1928, and from then Isherwood was considered one of the new literary lights.

Heard and Huxley had a significant role in converting Isherwood to pacifism. Noted at the time because he was one of the early writers to warn about rising fascism and to endorse an armed resistance.

Isherwood left England in 1939. After a brief period in New York, he followed Heard and Huxley to Los Angeles.

At first, he embraced Heard’s “New Pacifism,” as a discipline. Listening to him talk about mysticism and yoga sparked another flame. Heard and Huxley then introduced him to Swami Prabhavananda. When the war broke out, while Isherwood was a registered pacifist, he was also too old for the draft. The swami suggested he move into the Vedanta center. Through the war years he lived there, by his own description as a “demi-monk.”

It was during this time he assisted Swami Prabhavananda in producing a translation of the Bhagavad Gita.: The Song of God, which was published in 1944. This would be the translation I first read. In fact, I read all three of Prabhavananda and Isherwood collaborations, the Gita, Shankara’s Crest-Jewel of Discrimination, and How to Know God: The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali.

But it would be his wonderful 1965 study, Ramakrishna and His Disciples that would fire my adolescent imagination as I had turned from my Fundamentalist upbringing and quickly passed through a hard rationalist atheism. I cannot say how important it was to me at that turning moment in my life.

So, what can I say about these three. They were all from England’s privileged classes. Each enjoyed first rate classical educations. Two were gay. Each had success pretty much right from the start. Critics say Isherwood was less of an intellectual than either Heard or Huxley, they each were brilliant. And, each in their own ways touched my spiritual life. Heard largely indirectly, but Huxley and Isherwood through my reading quite a fair number of their books.

Because of them, I flirted with Vedanta. But only briefly. I admired much of what that tradition offered, and still does and I still admire them. What they did do was infuse me with a broad tolerance of the world’s spiritualities and implanted an assumption I could find wisdom, saving wisdom, anywhere around the world.

My journey would continue. My principal touchstone would turn out to be Zen Buddhism, informed in many ways by the rationalist and Transcendentalist Unitarian Universalism.

Today, from the vantage of my seventy-five years, I look back on these teachers of my youth. And I feel enormous gratitude. Tidal waves of gratitude.

Endless bows…

***

Here’s a clip of Alan Watts discussing Gerald Heard