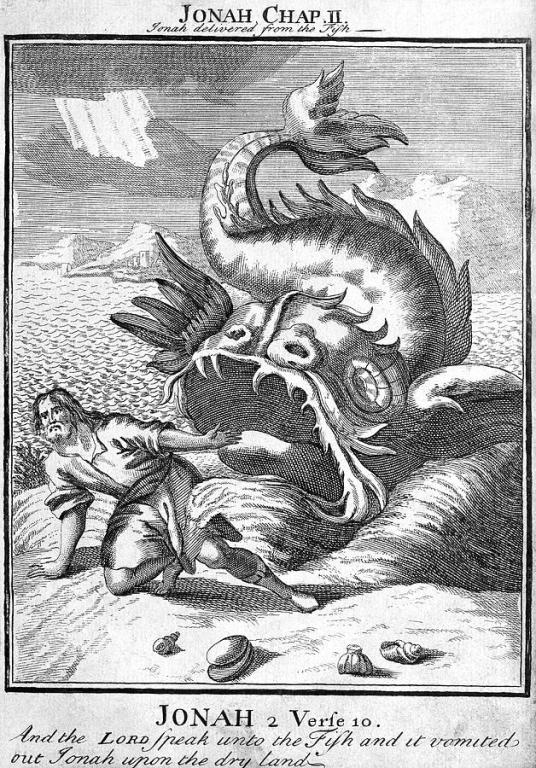

Engraving

by George Bernard

So, what is spirituality, anyway?

Philip Sheldrake is generally considered among the foremost academics studying the subject. He specializes in Christian spirituality. But out of his years of study has offered some insights into what spirituality seems to be as a current within religions writ large.

It is a current, a strand, an aspect. As the spiritual but not religious intuit, the major project of religion is social cohesion. Religion in human cultures is largely about defining who is in and who is out. Along with preserving the stories and rituals of a culture. Spirituality is connected to that project of shaping and sustaining culture, but it is also distinguishable. Spirituality is about the deepest currents of our human lives. It is where we find meaning. Spirituality is where we meet the gods, God, or ultimacy. Pick your term. Actually for me, because that sense of ultimacy is elusive and can be named so many ways, all of which feel to fall short of something that is met across cultures, I prefer to call it “the mystery.”

Spirituality is that part of a culture where individuals can meet the mystery of our existence both within that culture and beyond it.

Professor Sheldrake identifies four broad categories, or types, or styles of spirituality. His terms for these are “ascetical,” “mystical,” “active-practical,” and “prophetic-critical.” He doesn’t see any of them as completely separate from the others.

I look at his categories and I see a natural ordering. The root element is what he calls mystical.

This is the desire to know the gods, God, ultimacy. The mystery. It’s a deeply personal project. As the old Zen line goes, it’s like wanting to take a drink of water and to know for oneself whether it is cool or warm. Jewish Kabbalists, those fourth century Christian desert fathers and mothers, Sufis, and medieval Chinese Zen masters immediately come to mind.

The ascetical type or style has been historically the most common way people approach the mystery. It’s what you might imagine life would be about in a monastery, or among people with strong spiritual disciplines. Rule. Rhythm. Prayer or meditation. Intentional simplicity. Trappist or Zen monks each fit this bill. Perhaps silent meeting Quakers, as well.

Then there’s kind of a turn from inward focused spirituality, outward. Here we find the third in the good professors list, the active-practical. It focuses on life in the here and now as the spiritual project. It’s where we find lives of service. That call to feed the hungry, to cloth the naked, to visit the imprisoned. Catholic Worker houses of hospitality come to mind. Probably any religiously based soup kitchen or food bank would be another example.

The fourth is prophetic-critical. I think of those ancient Hebrew prophets railing against those who’ve abandoned the poor and sought only their own personal benefit. Of these my favorite is Jonah. He’s no one’s idea of a nice guy, who only after trying to avoid the job, you may recall in the story he’s running away from the job, when God has him swallowed by a great fish and then spit up on the beach heading back to the city where he’s supposed to prophecy, calling people back from iniquity. In those time iniquity is more commonly mistreating the poor. But the sin is not actually named in the story.

Whatever. He’s my favorite of the prophets because he’s a self-centered jerk. As you no doubt recall, he prophecies, and the people hear the word and mend their ways. Then he goes into a rage because they don’t get the fire and brimstone part. The major point here, it that mystery, which seems to be most of all about love and a calling back is extended to everyone. And the person chosen to be the pivot in the turn is himself unworthy.

All these forms of spirituality are about how you and I are, and what you and I may actually be within all our messiness. It is the call of the mystery, and our individual response to it. As we are, just as we are.

In one of his fourteen books, Oxford University Press’s Spirituality: A Very Short Introduction, Professor Sheldrake suggests this prophetic-critical spirituality is a relatively modern thing. Me, I think of Jonah. And for that matter Elijah, Elisha, Hosea, and Amos, as well. Clearly it’s ancient. What I think the professor means is that this prophetic spirituality has been emerging in modernity in some very interesting and distinctive ways.

I suggest this prophetic spirituality turns on the idea of justice as some deep sense that arises naturally within our human hearts. Maybe from the same place one might find that sense of the gods, or God, or ultimacy. Justice and a sense of justice for all seems to arise from that deep place which is the mystery.

But it isn’t just private. Among the oldest definitions of justice might be found in the preface to Plato’s Republic. For Plato justice is “rendering to everyone their due.” It’s easy to see justice as the Golden Rule applied with the authority of the state. Of course, with that power, it’s not a hard slide to an eye for an eye. So, justice is a dangerous thing. And needs cautions.

It’s within the spiritual sense of justice, within that prophetic spirituality, that the call for justice is more likely to be healthful and healing rather than about retribution or vengeance. It is a calling of our hearts and hands to something deep.

Looking for modern examples isn’t hard. Bishop William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign certainly is prophetic spirituality. I notice this past week was the Reverend Troy Perry’s birthday. I think the Metropolitan Community Church he founded as an evangelical expression of prophetic spirituality is another. I also think of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, which has been very important to me. However we understand our boundless nature, it calls us to serve the lost and left behind. Prophetic spirituality is about leaving no one behind.

And. I think of the Unitarian Universalist Association. And something more. There is a religious radicalism that is arising, of which the UUA is simply the largest organized expression. As my colleague in UU ministry, the Reverend Victoria Weinstein notes of UUs specifically, but it is applicable to a rising interfaith movement, we are about something new, “we sail the seas of a pluralism that the mainline church dabs its toe in on the shore.” This pluralism project, if you will, this way of radical religion is something new. And with that broadness, it can be hard to see where we find the depths.

Here I have a suggestion. Perhaps ours is the first of the spiritual traditions to find that prophetic spirituality as the north star of our way. Absolutely, it exists and is flourishing among the Axiel age religions and their successors in Islam and the Sikh tradition. But for many of the rising pluralistic traditions, and especially among Unitarian Universalists, I suggest this prophetic spirituality is the guiding principle. It is what pulls our hearts and guides our actions.

What is true in Professor Sheldrake’s assertion, I believe, is that this prophetic approach to the spiritual life started to arise most clearly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. And for us not incidentally as Transcendentalism shifted the rising Unitarian and not long after Universalist communities into spiritual pluralism.

Probably the most significant application of a prophetic spirituality as a quest for justice arises in India in the first half of the twentieth century, which most of us know through Mohandas Gandhi. In the same time frame, currents of Engaged Buddhism also arises within the anti-colonialist movement. And it quickly expands from South and East Asia to the West. Dr King, after all, was a disciple of Gandhi. Who, by the bye, was partially influenced by Henry Thoreau.

What I’ve noticed is that starting somewhere in the early mid nineteenth century, some grand feedback loops between east and west, broadly speaking we can say between Abrahamic and Dharmic traditions (although its bigger than that) began. And with that we’ve begun to see prophetic spiritualities grounded in a clear seeing into our radical interconnections as for many of us the best description of the mystery.

I’m particularly interested in how this prophetic spirituality has grown and matured among us as Unitarian Universalists. One great example is Theodore Parker.

I’ve mentioned him before. He was the Transcendentalist Unitarian minister who in the years before the Civil War hid runaway slaves in his home and who wrote his sermons with a loaded pistol resting on his desk. He was a member of the Secret Six, who underwrote John Brown’s abortive attempt to arm a slave rebellion.

Parker’s Transcendentalism was rooted in a direct encounter with the divine, which he described as “great primal intuitions of nature that depend on no logical process of demonstration,” that called him into a life of action. Here I believe that root of spirituality, the mystical, was deep in Parker’s life. And it demanded manifestation. He gave, he served. And he railed the voice of God against all forms of oppression.

I’ve also shared this before. And I expect I will again. It’s really important. In 1853 Theodore Parker preached a sermon, “Justice and the Conscience.” There he proclaimed, “I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; (but) I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.”

Part of what’s important for me is how he saw the whole of our existence bound up intimately. He used the language of western spiritualities which feature beginnings and endings. But just assuredly as within the great cycles of eastern spiritualities he saw everything is connected.

A century and almost a decade later, Dr Martin Luther King, Jr, who deeply admired Parker, and who often cited the old Transcendentalist in his sermons, called out to us, “I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because truth crushed to earth will rise again. How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever. How long? Not long, because you shall reap what you sow…. How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Parker’s influence continues, modified, corrected, expanded. Four decades and three years after Dr King’s words, then president Barack Obama, speaking on the anniversary of King’s assassination, proclaimed, “Dr. King once said that the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. It bends towards justice, but here is the thing: it does not bend on its own. It bends because each of us in our own ways put our hand on that arc and we bend it in the direction of justice….”

Here I think we find what a Prophetic spirituality calls us to: To see the connections, to reflect on those connections, and then to act in the world inspired by those connections, each of us, in our own way. This is the heart of our prophetic spirituality.

I also love that the child nurtured by his Unitarian Universalist grandparents was able to close the loop, to explain the fullness of our prophetic spirituality. He knew to add in those hands in part because his grandmother, with all her shortcomings, showed him how.

We are living in very complicated times. In some ways for many people things have never been better. More people enjoy a fair share of the fruits of their labors than at any other time in history. Around the world women and LGBTQ people are standing up for long denied rights.

At the same time climate change is upon us. This is the hottest summer they can count back one hundred and twenty thousand years. And those LGBTQ rights? Well, we know they’re under assault. And women’s rights, well. And, if you’ve driven here, how many homeless people did you have to drive by?

And when was the last time an American presidential campaign centered on naked and unalloyed revenge?

These are complex and dangerous times.

So, what does it mean to be a Unitarian Universalist in this time, and in this place? What does it mean to participate within a prophetic spirituality?

Well, you know, if you look through the dust flying around, it’s pretty straight-forward. We commit to looking at ourselves and the world, as deeply as possible. We commit to seeing the connections. You know, what by its many names, is the mystery. And with that we commit to putting our hand on that arc.

For UUs I have some suggestions. Deepen the other senses of the spiritual. The grand intuition is expressed in the seventh principle. Whether that exact language continues or not, the intuition of a deep interconnectedness is not philosophical. When we speak of love, that’s what we’re talking about.

I would also encourage us to embrace some practices. The most obvious I feel are those Buddhist disciplines of presence. Either in a traditional form or in one of the secular adaptions like Jon Kabat-Zin’s mindfulness based stress reduction. Here’s a secret. Its actually about something a lot deeper than stress reduction.

Of course, we will make mistakes. We will lose sight of the connections, our hearts will turn sour, we will despair. But if we recall the prophetic voice is rooted itself in something deeper, then we can prevail. We need to recall our intuition of service and action comes from the deepest truths of our hearts: we are one. We are one family. We are intimately connected.

That is the mystery.

Look around and we see your relatives.

This is the very same seeing that informed Theodore Parker, and which informs our Unitarian Universalist spiritual way today. If you see our essential connection with each other is nothing less than the divine itself, the gods, God, ultimacy, the great mystery; then with false steps and mistakes along the way, of course with false steps and mistakes, like Jonah, as people, with all that means, we will nonetheless go in the right direction.

We will put our hands to work, and we will bend that arc.

Our prophetic spirituality.

Amen.