THE GOD OF DIRT

A Reflection on the Spirituality of Mary Oliver

I.

Something came up

out of the dark.

It wasn’t anything I had ever seen before.

It wasn’t an animal

or a flower,

unless it was both.

Something came up out of the water,

a head the size of a cat

but muddy and without ears.

I don’t know what God is.

I don’t know what death is.

But I believe they have between them

some fervent and necessary arrangement.

II.

Sometimes

melancholy leaves me breathless…

III.

Water from the heavens! Electricity from the source!

Both of them mad to create something!

The lighting brighter than any flower.

The thunder without a drowsy bone in its body.

IV.

Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

V.

Two or three times in my life I discovered love.

Each time it seemed to solve everything.

Each time it solved a great many things

but not everything.

Yet left me as grateful as if it had indeed, and

thoroughly, solved everything.

VI.

God, rest in my heart

and fortify me,

take away my hunger for answers,

let the hours play upon my body

like the hands of my beloved.

Let the cathead appear again—

the smallest of your mysteries,

some wild cousin of my own blood probably—

some cousin of my own wild blood probably,

in the black dinner-bowl of the pond.

VII.

Death waits for me, I know it, around

one corner or another.

This doesn’t amuse me.

Neither does it frighten me.

After the rain, I went back into the field of sunflowers.

It was cool, and I was anything but drowsy.

I walked slowly, and listened

to the crazy roots, in the drenched earth, laughing and growing.

Mary Oliver

In 2006 Mary Oliver gave the Ware Lecture at the Unitarian Universalist General Assembly. To be invited to give the Ware Lecture is one of the highest honors in the Unitarian Universalist world. Among those who’ve presented are Cornel West, Kurt Vonnegut, Reinhold Niebuhr, Jane Addams, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Additionally, three of Oliver’s poems are enshrined in the current UU Hymnal. And, her principal publisher was UU owned Beacon Press, the last of the religiously owned major publishing houses. She is cited so frequently in UU sermons, that most present at the Ware assumed she was a UU. So, when she passingly referenced attending mass with her wife, there was an audible collective inhalation.

People were shocked that she was Roman Catholic. Of course, she wasn’t. The mass she referred to was Episcopal. She and her life-long partner Molly Malone Cook were members of St Mary of the Harbor Episcopal church in Provincetown. Actually, “member” is a bit complicated. I gather she never actually joined due to scruples around the doctrine of the resurrection, and didn’t want to make the credal assertion, even though many if not most Episcopalians seem to take it poetically, themselves. She did, I’ve read, serve on the altar guild for a time. And she once famously referred to the Episcopal church as “that strange, difficult, and beautiful church.” So, Episcopal, more than not.

And there are more reasons than I could count that UUs would find her ours, as well. We are, after all, another strange, difficult, and beautiful church. Maybe not as beautiful as the Episcopals, but not doubt every bit as strange and difficult. Mary Oliver is a much beloved poet among religious liberals, whatever our denominational affiliation or not. I would call her a poet of mystical specificity. She sings to the mystery of things. She draws our hearts to astonishment in small things. She invites us, if you will, to the God of dirt.

The god of dirt

came up to me many times and said

so many wise and delectable things,

I lay

on the grass listening

to his dog voice,

frog voice; now,

he said, and now,

and never once mentioned forever

Scruples about the resurrection. Hers is a type of naturalistic spirituality. Dead is dead. As life is life. As is some fervent and necessary arrangement between them. In addition to Unitarians and Episcopalians, Mary Oliver is much beloved in Western Zen Buddhist circles.

In some ways she really is the patron saint of the spiritual but not religious. And, in some ways, not. Unitarians, Episcopalians, Zen Buddhists. And the spiritually liberal of maybe all religions. And, not restrained by any one of them. What she is, is a wonder and a joy, inviting us all into the intimate way.

Mary Jane Oliver was born on the 10th of September 1935, in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. She is said to have started writing poetry at fourteen. Oliver went on to study at Ohio State and Vassar. But left her college years without a degree.

Her endless passion was writing. She was twenty-eight when her first collection of poems, No Voyage and Other Poems was published to critical acclaim. Her fifth collection American Primative was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. Later her New and Selected Poems won the National Book Award.

Oliver and her partner the photographer Molly Malone Cook lived largely in Provincetown, Massachusetts for some forty years, continuing there until Cook’s death in 2005. After which Oliver relocated to Florida. She died there on the 17th of January 2019. She was eighty-three.

Oliver is often compared to Emily Dickinson. Another poet UUs claim when it’s not exactly so. Reading her we can see why Oliver and Dickinson can be seen keeping company. And of course, there’s much more to her than that similarity of sparse spirit in their writing. The article about Oliver in Wikipedia summarizes how “Her poetry combines dark introspection with joyous release. Although she has been criticized for writing poetry that assumes a dangerously close relationship of women with nature, she finds the self is only strengthened through an immersion with nature. Oliver is also known for her unadorned language and accessible themes. While the Harvard Review describes her work as an antidote to ‘inattention and the baroque conventions of our social and professional lives. She was a poet of wisdom and generosity whose vision allows us to look intimately at a world not of our making.’”

A liberal spiritual spirit runs deeply through her writings. I love how Episcopal canon, Reverend George Maxwell opined “If it were up to me, her poem “The Summer Day” would be read in every confirmation service, and “Wild Geese” at every wedding.”

As I suggested Oliver has been particularly fashionable within Unitarian Universalist circles. I do agree that perhaps too many of our preachers seem to think she and maybe Rumi are the only poets we are allowed to quote. There are reasons so many of us just assumed she was UU. And so, of course, in good time there have been those among us who have criticized her work. Several of these criticisms describe her focus as too small and inoffensive. While others criticized her close identification of women and nature as, well, too close.

That said, me, I’ve found her a deeply important voice pointing to many truths that mark the best of our contemporary Western spiritualities. As Canon Maxwell says, her poetry is “earthy, sacramental, and prayerful; responsive to mystery; and inclined to gratitude…” I think of her, like Dickinson, if not directly, nonetheless, as a true heir to the Transcendentalists. Carrying forward the best of that mixed bag, offering a subtle yet compelling nature mysticism.

You read something like her Summer Day, and you can see why she is so important to anyone seeking the mystery within the ordinary.

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

this grasshopper, I mean—

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down—

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

At her death the writer and musician Josh Jones summed up a lot when he wrote of Oliver:

“The word ‘earnest’ comes up often as faint praise in reviews of Oliver’s poetry (Garner tidily sums up her work as ‘earnest poems about nature’). The implication is that her poems are slight, simple, unrefined. This perhaps inevitably happens to accessible poets who become famous in life, but it is also a serious misreading. Oliver’s work is full of paradoxes, ambiguities, and the hard wisdom of a mature moral vision. She is ‘among the few American poets,’ critic Alicia Ostriker writes, ‘who can describe and transmit ecstasy, while retaining a practical awareness of the world as one of predators and prey.’ In her work, she faces suffering with ‘cold, sharp eyes,’ confronting ‘steadily,’ Ostriker goes on, ‘what she cannot change.’”

I think there’s a truth in some of the criticisms. Her work is inward. And there’s a next step. There’s always a call to reach out. As well. We are beings. And we are doers. But we cannot do in any healthful way without rooting our being. We need to know who we are. And few sing the truth of who we are is powerfully as Mary Oliver.

With that I gift you all with this, the tag end of Mary Oliver’s In Blackwater Woods.

It is not too much to say it is close to the sum total of my spiritual life. Unitarian minister. Zen teacher. A person who has given a lifetime to the intimate way. Just about all of it. Nearly the whole thing. As we say in Zen, a full eighty percent.

Look, the trees are turning

their own bodies into pillars

of light,

are giving off the rich fragrance of cinnamon and fulfillment,

the long tapers

of cattails

are bursting and floating away over the blue shoulders

of the ponds,

and every pond,

no matter what its

name is, is

nameless now.

Every year

everything

I have ever learned

in my lifetime

leads back to this: the fires and the black river of loss whose other side

is salvation,

whose meaning

none of us will ever know. To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go,

to let it go.

Let me repeat that last part.

“To live in this world, you must be able to do three things: to love what is mortal; to hold it against your bones knowing your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go.”

You can unpack that teaching, that pointer, that koan for a lifetime. It is the song of the real. It calls us to the God of dirt. She, Mary Oliver calls us to our lives. Nothing less.

Do I hear an amen?

Amen.

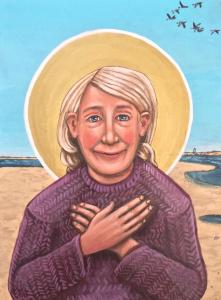

The image “Mary Oliver” is by Kelly Latimore. Prints are available at Fine Art America.