The Dark Soil of God

A Zen Meditation on the Psalms

James Ishmael Ford

The earth belongs to the Divine

and everything on it.

For the Divine wove it out of the emptiness of space

and breathed life into every corner,

bringing forth all life,

and all of it precious.

Who is fit to care for this

and worthy to act as God’s representative?

Those passionate for truth,

who are horrified by injustice,

who stand with the poor,

and take up the cause of the helpless.

Those who let go of selfishness,

and see the sacred hoop of the world,

refusing exploitation of any creature,

or the fouling of her waters and land

Their strength is in compassion.

Divine light shines through their hearts,

and their children’s children will be blessed

and bless the world.

Psalm 24 (paraphrase by James Ishmael Ford)

As some of my friends know, I’m visiting a former professor from seminary who became a colleague and friend in the ministry. A while back he suffered from a swarm of strokes which left him severely disabled. Now after several years of decline and more strokes he’s in hospice.

His ability to communicate is limited. But there’s a brain in there, and while it seems through a fog, he knows what’s what. He identifies as a Unitarian Universalist Christian. Not a lot of them on the West coast, but at one time both Unitarians and Universalists would have assumed Christian, and there’s a continuing thread of radical Christianity among us to this day. So, UU Christian is perhaps not so strange as it might seem here in Channing Hall, incidentally named for a radical Unitarian Christian, at the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles.

All a bit of a long way around the barn to say David and I ended up reading the psalms together. In truth, I started by reading them to him, looking for something that might be useful in these hard days. But along the way I’ve been pulled in and found we really are reading them together.

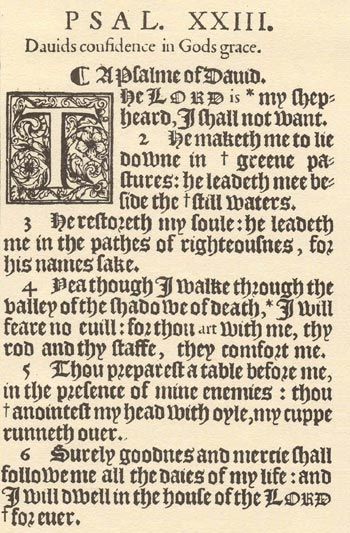

The psalms are a wildly diverse selection of ancient near eastern religious poetry. The Psalter, that is the collection of poems taken together, depending on how one counts, either 151 or more commonly 150, reside at the center of much of private and corporate prayer within both Jewish and traditional Christian worship. They’re uneven, to say the least. Ancient war chants, anyone? But the best parts of them are astonishing, subtle, and compelling. And within the rhythms of David’s and my weekly visits and our reading different translations of the various psalms one after the other, they began to touch me in very real ways. I could see how they genuinely could be the basis of an inner quest, guard rails for meditation as well as prayer of several kinds.

I knew a bit from earlier reading, and a little more from my seminary days, but now sorting it out with a bit more focus, I outlined what we can know about the texts. The psalms themselves are, well, I find I keep coming back to that word: ancient. Most scholars believe psalm 90 is likely the oldest, while psalm 29 as a gloss on a much older Caananite hymn is another candidate. Some enthusiasts suggest the oldest of the psalms were written more than three thousand years ago. While that’s, in all likelihood, a stretch; many, possibly most were written before the Babylonian captivity in the sixth century before our common era.

They were compiled as a liturgical document sometime in the Second Temple period. So, somewhere after about 500 BCE. They are gathered as the first volume of the third part of the Hebrew Bible, the Ketubim, the “Writings.” In the King James Version there’s a little trick of it being right in the middle of the book, so it’s easy to find them. The psalms are the longest book of the Bible, consisting entirely of religious poetry. Although the “religion” of some of them is hard to see. Did I mention war chants? Perhaps they all were originally meant to be accompanied by music and many offer some guidance to the appropriate instrument to be played as they were recited or sung.

The collection of the Psalms is traditionally divided into five books, perhaps echoing the Five books of Moses. Contemporary scholarship suggests the first three of these books, Psalms 1-89 are the oldest strata of the collection, the pretty clearly before the Babylonian Captivity part. The balance of the psalms don’t appear to have been settled as part of the canon until the turn into our common era, roughly the time of Jesus.

There are clusters of psalms with related significance. But the only arc most can see in the collection is a general movement from lament to praise. Some psalms are obviously meant for corporate worship, while many seem very intimate and personal. In addition to lament and praise, some are didactic, little sermons. Nearly half the psalms are attributed to the semi-legendary king David.

The major difference in Jewish and Christian reading of the psalms is how the Christian community interprets many of them through the lens of Christology, seeing Jesus anticipated and sometimes explained. In fact from antiquity Christians had two broad approaches to the psalms. The Antiochian school favored a more literal reading, while the Alexandrian school used analogy in their quest for deeper and sometimes mystical insights.

The fourth century scholar bishop Athanasius of Alexandria described the psalms as a “mirror of the heart.” The Oxford Handbook of the Psalms quotes him describing them as revealing “in all their great variety the movement of the human soul.” The Handbook notes that from antiquity Jewish interpretation “mines both the plain sense and the hidden meanings of the text, even enlisting numerology…” as Hebrew letters are also their numbers, in that quest of the ever deeper.

So, from the beginning, people saw layers of meanings in the psalms.

For me, first as a Buddhist and second as a person who is interested in what scholarship has to say about religions, I find the God of the psalms to be many things. There’s a very archaic god at base, something to do with piling clouds, storms, lightening strikes, and desert rain. And then folded into that God over ages upon ages, layers upon layers of the human heart’s discovery. I’ve found allowing the whole thing from lightning strikes to the still small voice, to be intimate, to be personal, a critical invitation. I’ve tried hard not to turn from those layers after layers as they present. And it has opened me in what seems deeply rich ways.

I find this endlessly multifaceted divine not really a lot different than that mysterious pregnant emptiness at the foundation point of Mahayana Buddhism. Śūnyatā. Not precisely one. Not exactly two. In religious studies it’s called nonduality.

Nonduality is a current found within the world’s mystical traditions. Unlike with Buddhism, which is grounded if you will, in the nondual, in Judaism and Christianity (and as an aside here their sister religion Islam) the nondual of Abrahamic traditions re minority reports. There, but rarely, if ever, led with. They are expressed, sometimes implicitly, the quietest of whispers, and sometimes explicitly, a shout, a firm grabbing of one’s shoulders, a great shake, and an invitation for our own encounter.

And this is amazingly rich. There are ways the nondual of my Zen Buddhism and the nondual of the Abrahamic mystical traditions can challenge and inform each other. For instance, Zen’s “empty,” sunyata is a placeholder. It doesn’t mean vacuity. Although, that actually is sometimes a word used to translate sunyata. You know, just to remind us there are those layers upon layers to be encountered as we turn to the fundamental matter, to finding that place at the center of our human heart’s longing.

As to the Abrahamic traditions, I have on occasion found another term from Western antiquity, pleroma, helpful as an alternative to what is misleading about emptiness. Pleroma means fullness And, a fascinating and useful, if of course itself ultimately misleading, as a term for that fundamental encounter of our hearts. I suggest Pregnant could be another good, if also as is always the case, misleading word. Empty. Full. Pregnant. God.

We approach this matter obliquely, through a glass darkly.

Many of my friends do not approve of God language. Some might be in this room. We’ve seen the ill of literalist versions of religions, especially when their adherents have political power. Lots to dislike. And at base the idea of a big human-like consciousness at the center of things, controlling things, certainly seems to me a classic example of projection. So, when my friends don’t like Go, they especially don’t like that archaic storm god at the earliest layering of the Hebrew scriptures.

And that God is without any doubt found in the psalms. Look at that psalm 29, the one lifted from the Canaanites, sometime. My god is better than your god. My daddy can beat up your daddy. It’s there. But, I find it simply another layer of our human heart. Projections. Transference. Wonder. Mystery. Curiosity. All faces of the divine.

I’ve thought it helpful to understand my actual lived encounter with sunyata on occasion is not unlike being possessed by the god. This is a way many human beings name an encounter that precedes words. Not the only way. But a powerful way. With this, for me, that nuanced and ultimately nondual God that can be if not always found in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, has long been okay. Actually, more than okay.

With that back to my friend, back to David. With all that God hanging in the back, more layers if you will, my project was meeting with a friend whose cognitive functions were beginning to slip, whose needs were ever more immediate and pressing. Life and death and the mysterious and terrible thing jumping like an electric charge between them. That. Perhaps you know it for yourself? David and I have been turning toward the most intimate together.

So, I began to search for those psalms that might be illuminated by a sense of nonduality. And to let most of the others go. Both David and loved that psalm we used in today’s chalice lighting, that call to justice as the work of God. Psalm 24. In fact, the Psalms often fit into several categories. So, while calling us to the work of justice, Psalm 24 absolutely has a mystical element to it. One of the great teachings I see more in Judaism than in its daughter religions is how everything turns practical very quickly, including our meeting with the divine. In Psalm 24, meeting God is a call to manifesting justice.

Now, in the collected writings of the Daoist master Zhuangzi scholars have detected writings they’re confident the ancient sage actually wrote, while there are other parts attributed to him but were probably not his composition. This is not all that unusual with texts from antiquity, especially of the spiritual kind. For instance the obviously two different authors writing as “Paul” in the New Testament is a pretty good example. One is an ecstatic where within the mystical Jesus there is no other, no Greek nor Jew, no man nor woman. While the other writer, well he’s an asshole. With Zhuangzi, the “authentic” texts are called the “Inner Chapters.”

I’m much taken with the term Inner Chapters. I’m not claiming there are inner or truer texts among the Psalter, beyond noting the first 89 are generally assumed to be much older than the rest. But. What there are, are psalms that touch the heart more than others might.

And so, I began to look for my own Inner Chapters. To help I started with two Buddhist sources. Of course. The Zen poets Stephen Mitchell and Norman Fischer have selected psalms to translate into English poetry. It’s worth noting beyond his poetry chops, one of them, Norman is also a recognized Zen master. I’ve found other sources helpful. I love the King James Version, even though its written in the same language as Shakespeare and is equally hard to discern sometimes. But I’m especially helped by the Jewish Publication Society’s 1982 translation. This project is ongoing and I’m not ready to report out a definitive number for my Inner Chapters. But right now I’m finding something fewer than thirty out of that hundred and fifty really calling to me.

The psalm 24 we lit the chalice with, is certainly one. We don’t have a lot of time, left. But here’s another.The 137th is largely a lament. In my free adaptation.

By the rivers of Babylon, we sat down and wept, recalling Zion. We hung our harps in the thicket of willows and were silent. But our captives demanded our songs, forcing smiles on our lips. They said sing those songs of Zion. But how can we? How can we sing the Lord‘s song in such a strange land? If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember you if I do not recall Jerusalem as my chief joy, let my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth.

Who doesn’t know this hurt? This longing? In one sense or another it is a cry from all our hearts. I believe this is a song of the deepest human, it touches the profound wrong that is the great intuition of most all religions. It is the starting point to a journey, and eventually it can take us to our true joy.

But then, there’s a turning. Something truly terrible.

Remember, O Lord, the children of Edom; who cried out, tear it down, tear it down, even to the foundation. O daughter of Babylon, I will be happy to take your children and dash their skulls against the rocks.

Calling down curses on one’s tormenters in the worst possible way. In theological language this is called imprecatory, it means calling down curses. There are almost a dozen psalms that fit that bill. Not my Inner Chapters. But. I think of that curse as such a terrible addenda to one of the most beautiful of the laments. This is why a lot of us moderns have little taste for the psalms. And, honestly, part of why I hadn’t given the psalms a lot of thought when I think about spiritual disciplines before this time of visiting David. War chants.

But. Or, more appropriately, and. I’ve read that psalm in a lot of different versions with David. They’ve washed over me. And I’m haunted by the deep humanity of it all. I find myself forced to note deep sorrow often includes a curse. David’s situation is horrific. He gets cursing. And I get it while sitting with him. The frustration is unspeakable. Reading the psalm, all of it, forces me to pause, to notice, to wonder at the human condition, at my human condition. So, I don’t need a lot of that, but in my Inner Chapters, I keep one of the cursing psalms. This one.

It’s all about paying attention. I find I’ve been invited into an intimate encounter with some very dark parts of my heart. Sometimes it’s shit. Plain and simple. And sometimes it is the rich soil that allows things to grow. And sometimes there is no way to sort these parts out. Layer upon layer intertwined, becoming. Each it. And each not quite it.

One more example. The 92nd Psalm, for instance. In my dance, as my words, although shared and departing from some ancient author:

It is good to sing praise to you, my heart.

To give thanks for the blessings of life,

To notice love coursing through my body in the morning

And faithfulness through the night.

I hear our human voices as music,

And silence as melody.

I delight in your world;

You make my body sing with joy.

How great is your goodness.

How unfathomable your deep currents,

Not seen by eyes

Not grasped by mind

Everything united

Everything touching.

The mess of life

Shows everything connected

Everything the eternal dharma.

The wise heart flourishes like palm trees

Grows like the cedars of Lebanon

Planted in the deep dark soil of God,

Leaves relentlessly turning to the light

Bearing fruit into old age

Living the truth

Of perfect unity.

Some of these psalms definitely are koans. Koans from the Zen tradition, in the sense of an assertion about an aspect of the real, bound up together with an invitation. Psalms, some of them, as koans.

I am trying to follow that invitation. Even into my curses. Even into the hell realms. Into the deep and dark. And. And, very much. Into the light like a turning leaf.

For me it works.

The ancient way of the children of Abraham and Sarah.

Intimacy upon intimacy…

Amen.