As some of my friends know, I’m visiting an old colleague and friend who identifies as a Unitarian Universalist Christian. Suffering from a mass of strokes he can’t really communicate much. So, we’ve ended up reading the Psalms together.

I’ve pulled about fifty-two from various recommendations of what might be considered the nub of that ancient collection. With my friend I take one and then read the King James Version, then the Jewish Publications Society version, followed by Stephen Mitchell’s poetic renditions, then Norman Fischer’s, and last Nan Merrill’s adaptation of the psalm into a prayer. It works for us.

This ancient prayer cycle has caught me. It is rich and terrible, and forces me to think about a lot of things I don’t normally think about. And I’ve noticed there’s an even deeper invitation that can, when I’m willing, take me rather closer to the bone than thinking about it.

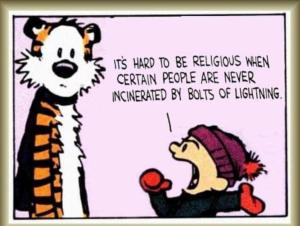

For example, the imprecatory psalms. Imprecatory is a term I only vaguely recalled from my seminary days. The term comes from the archaic verb “imprecate,” which means to utter a curse or invoke some evil against someone or some thing. By various calculation there are three or five or seven kinds of psalms. But one among that number that has to be noted is the imprecatory. Of the hundred and fifty psalms, fourteen are generally counted as pretty much out and out cursing someone.

For those who like lists: 7, 35, 55, 58, 59, 69, 79, 109. and 137.

The 137th is largely a lament.

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How shall we sing the Lord‘s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy.

Who doesn’t know this hurt? This longing? In one sense or another it is a cry from all our hearts. I believe this is a song of the deepest human, it touches the profound wrong that is the great intuition of most all religions.

But, then, there’s a turning.

Remember, O Lord, the children of Edom in the day of Jerusalem; who said, Rase it, rase it, even to the foundation thereof. O daughter of Babylon, who art to be destroyed; happy shall he be, that rewardeth thee as thou hast served us. Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones.

That calling down curses on one’s tormenters.

Why a lot of us moderns have little taste for the psalms. There’s a fair amount of this salted throughout the collection. And part of why I haven’t given the psalms a lot of thought when I think about spiritual disciplines.

For me revisiting these week after week, month after month, I’ve begun to notice things. A gift of sorts. Not least of which is why the psalms are a cornerstone of the spiritual practices in both Judaism and Christianity.

For one, as a Buddhist, I find the God of the psalms to be many things. There’s a very archaic god at base and then layers upon layers of our heart’s discovery. I’ve found allowing the whole thing to be personal, a critical invitation, and to not turn from those layers after layers as they present opens me in interesting if not always fun ways. I see find this endlessly multifaceted divine not really a lot different than what I name in my spiritual life “emptiness.” Emptiness is one of the several common translations of the Buddhist term Śūnyatā.

Emptiness is a placeholder. It doesn’t mean vacuity. Although, that actually is another word used to translate sunyata. Just to keep it rich. Just to let us know there are layers upon layers to be encountered as we turn to the fundamental matter. I have on occasion found another term from Western antiquity, pleroma, helpful as an alternative to emptiness. Pleroma means fullness, an equally useful and equally misleading term for that fundamental encounter. Pregnant could be another word.

Many of my friends do not approve of God language. They especially don’t like that archaic storm god. I’ve thought it helpful to understand my actual lived encounter with sunyata on occasion is like being possessed by the god. A way to name the encounter. Not as it. Well, not precisely. More layers. And so, for me, God has long been okay.

I have come to love the pleas and the adoration and the sheer awe the writers of these poems express. I know many of these experiences. Maybe all of them.

I get the praise parts. I get the thanksgivings, which are a bit different than praise. And I get the laments. These are so naturally human. And. Well. I try to hide it. I even think I rarely feel it. But I am capable of imprecatory feelings if not actual prayers. More of that deeply human. More of that most personal.

Even like with the god parts I don’t like, but do feel birthing within the great mess when I pay attention, I find I’ve been invited into an intimate encounter with some very dark parts of my heart. Layer upon layer. Each it. And each not quite it.

So. The Zen teacher is reading the Psalms.

I am beginning to treat them a bit like koans. Koans in the sense of an assertion about an aspect of the real together with an invitation. For me it works.

I am trying to follow that invitation. Even into my curses. Even into the hell realms. For me it works.

Doors open.

As the wise say nothing human is alien.

Possibilities.

To know is the gate to letting go.

And with that intimacy upon intimacy…