THE DAY AFTER CHRISTMAS

A Meditation on What Comes Next

James Ishmael Ford

Here we are. The day after Christmas.

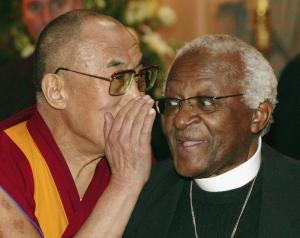

With a cup of coffee in hand I turned to the Associated Press newsfeed. The lead story this morning was that Desmond Tutu, retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, hero of the anti-apartheid movement, leader of the right for women to be ordained in his church, LGBTQ rights activist, ecological justice activist, Nobel laureate, really a life-long and tireless advocate for the dignity of human beings, and the possibilities for a love-informed justice in this world, died. He was ninety years old.

Among those who had words this morning, former President Barack Obama said he “was a mentor, a friend, and a moral compass for me and so many others.” Malala Yousafzai chose to quote the bishop for her eulogy, “Do your little bit of good where you are; it’s those little bits of good put together that overwhelm the world.”

A bit of good. The power of the small.

This is an interesting time. Perhaps a just right moment to pause and consider the small and the power of the small. The big has been much in our lives for several days now. The run up to our Western Christmas, which dominates our culture, is over. It’s a very big thing that’s been going on all around us. And now, a pause. This sense of pause would be here without the death of the bishop. But for me certainly his death strongly underscores this pause.

A turning is in the air. And it is bit of a moveable feast. Some things, really big, have already passed. Christmas. The bishop. And, of course, one more major day rushing hard on us. A date and a turning used as the common marker within our world culture. Even more ancient calendars, while still in use, take a back seat for a moment for this one.

We have passed the actual winter solstice, which was last Tuesday. You know it’s probably the real reason for the season. The marking of the longest night. And, finally, finally, with that the turning once again toward the light. Which because of the Gregorian calendar and its marker of a new beginning will mostly be noticed, counted, celebrated next week. In six days.

I think we can take all of these things together. Especially how it is a moveable feast. That is there are many things happening. The turnings here are many smaller things becoming something quite large. And of course a moment, a pause. We might catch a breath. And I strongly suggest we do.

Much of today’s reflection is about this pause, this breath, this moment. But the ride continues. That’s also part of it.

In this season we are caught up in some great liminal space. Liminal in that sense of standing in a place, or, perhaps best, standing in a moment, where the past and the future are both present. We’re living within some mutable boundary. There’s a threshold. We can notice it. And we’ve even put one foot across. Where the weight is, on which foot, however, is not so clear.

It feels dynamic. It feels uncertain. Even unbalanced. This moment.

It isn’t even clear whether it’s all to be taken solemnly, or in some other way. A bunch of years ago I was serving the Chandler UU congregation in Arizona on another Sunday that followed the day after Christmas. The way the church newsletter worked there I was expected to come up with sermon titles for the coming month. So, at the end of November I had to put a title to that day after Christmas. This was at a moment when most of my thinking was devoted to the run up to the all-consuming Christmas season, even in a Unitarian church, perhaps the biggest event of the year. So, I was a bit distracted and not overly concerned with what followed. I’d noticed in England and their Commonwealth this day after Sunday is called Boxing Day. Sounded good enough. So, I wrote down for my sermon title, “A Reflection on Boxing Day.”

When it was printed Kellie Walker our music minister came into my office and asked, “So, what is Boxing Day?” She needed something to start putting the music together for that Sunday. I said beyond some English thing, I didn’t have a clue. She gave me that look which most anyone who has a mother knows, and said, “James, what if it turns out its the day the English celebrate forcing the Chinese to buy opium?” Boxer rebellion, Boxing day. Makes sense if you think about it. And I admit I hadn’t thought about that possibility. Fortunately. it turns out today, Boxing Day is the day people serving others get small tokens for their service. Sort of an annual tip. So, the sermon didn’t have to deal with the worst of human behaviors. Although maybe that hangs in any moment of turning, what do we leave, what do we bring? And. How are those who serve, treated?

To be honest I don’t actually recall what I spoke about then. But serving and gratitude, while I can see a worthy reflection, isn’t what feels most important about this time. Although, again, maybe a hint of that. A part. What are the little things that connect us, that as the bishop noted, the bits that come together, and how do we acknowledge those who have cared for us in ways small or large?

In the Christian calendar today is also St Stephen’s Day. Stephen is the first official martyr of the Christian story. I believe there are things worth dying for. Although in general, I find it more important to reflect on what is worth living for. But, yes, what is worth dying for? That “most important” hangs in the back of my mind. Maybe not the point of the day, but part of it. For me.

Then I recalled how in my years serving at the First Unitarian Church of Providence, during our annual Christmas Eve service, a really big thing there, we usually ended the lessons and carols with a reading of Howard Thurman’s poem the Work of Christmas.

When the song of the angels is stilled, When the star in the sky is gone, When the kings and princes are home, When the shepherds are back with their flock, The work of Christmas begins:

To find the lost,

To heal the broken,

To feed the hungry,

To release the prisoner,

To rebuild the nations,

To bring peace among others,

To make music in the heart.

And that is what I find calling to me today. In this liminal season, of Christmas, and Passover, and Solstice, and, of course, a New Year, as we pass from the longest night, what is the work of a dawning hope?

Desmond Tutu’s life shows us what that can look like. As is the life of the author of that poem about the work of Christmas, Howard Thurman.

Reverend Thurman, if you don’t know him, was one of the more important if less widley known spiritual figures on the American scene in the Twentieth century. The grandson of slaves, he was raised within the warm embrace of the black Baptist church. He graduated in 1923 from one of the most famous historically black colleges and universities, Morehouse College. Then in 1926, while at what is now called Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, he was ordained a Baptist minister.

He served as a parish minister for a while but then was called into university chaplaincy. Spiritually, he became a disciple of the Quaker theologian Rufus Jones, coming to embrace the spiritual unity of all and with that a radical pacifism. While Dean of Howard University’s Rankin Chapel, he was part of that famous delegation of African American ministers who traveled to India to meet Mohandas Gandhi. His life was deeply focused on care and justice for the poor, racial justice and civil rights, as well as pacifism.

Later he founded the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco, which interestingly has had a long association with the Unitarian Universalist community. Its current minister is actually a Unitarian. But his most famous tenure was as Dean of Marsh Chapel at Boston University. While serving there Reverend Thurman was a mentor for Martin Luther King Jr, when he was engaged in his doctoral studies.

What’s so important about Howard Thurman to me is how he is counted as both a mystic and as a social justice activist. He was never confused about the deep connection between the quest for healing the broken heart and the work of healing broken bodies. Not unlike Desmond Tutu. He saw the connections. Profoundly. Deeply. Truly. And in some twenty books and as a teacher and chaplain at some very important educational institutions, he influenced a generation of seekers. Through those books, well, his influence continues.

We’ve had a moment. Christmas has come. If we’re just a little lucky, perhaps we’ve noticed a sense of hope birthing. It happens all the time. In the strangest of places. Which in part is why I love Christmas as a wondrous manifestation of this eternal return. Hope come as a baby born to the poor, to immigrants, to refugees. Hope. Always a small flame. Always a small bit. And in that poem Reverend Thurman notices the quiet that follows the moment of hope birthing. He rests in that quiet. Then. Out of that quiet, tells us what our hearts know, what we need to do.

This all very much reminds me of that wonderful line from the Transcendentalist Unitarian minister, and abolitionist, Theodore Parker. In a sermon he preached in 1853, “Justice and the Conscience,” Parker declared:

“I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.”

I am not the only one who has been touched by that line. About a hundred years later, a tad more, Martin Luther King, Jr, now thrust into the leadership of the Civil Rights movement, two weeks after Bloody Sunday, stood on the steps of the Alabama State Capital. Dr King a student of Gandhi and Thurman, and also of Theodore Parker, famously sang into our hearts:

“I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because truth crushed to earth will rise again. How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever. How long? Not long, because you shall reap what you sow…. How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

And that reminds me of another speech. In 2008, speaking on the 40th anniversary of Dr King’s assassination, then President Barack Obama, tied it all together. He brought the echo of Theodore Parker’s words, which Martin Luther King, Jr made his own, and washed through the same sense that Howard Thurman and Desmond Tutu, each calls us to:

“Dr. King once said that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice. It bends towards justice, but here is the thing: it does not bend on its own. It bends because each of us in our own ways put our hand on that arc and we bend it in the direction of justice….”

Our little bit of good. And how it becomes something great.

I think about the moral universe. I think about the arc of history. And I think about putting our hand on that arc and bending toward justice. Each a little bit. But taken together great things. I feel my heart responding. I believe words like moral universe and arc and even justice are messy things. They don’t really capture the fullness of the mystery of existence. At least for me. For instance, without the hands and the bending I don’t see a moral universe. With those actions, those small bits, well, then a moral universe is birthed. Like Christmas, a most unlikely event. And yet. And yet.

Within the mystery that is our life, we exist within a dynamic. We are mutually creating something. It doesn’t have to be good. But it is being created. The question is how does it become good. What does that good look like? What might be the little bit for each of us?

Here I find myself returning to the moment, this moment where the past and the future have collapsed and we may even have taken one step into that future. But it is a stepping forward filled with uncertainty. With what is called in the Zen tradition, not knowing. Perhaps if we’re smart, it is a stepping forward with fear and trembling.

But, maybe also with hope? Can we bring the horrors of our humanity that can make a reasonable person ignorant of Boxing Day think it might be about the Boxer Rebellion, an uprising against outsiders trying to force a nation to buy opium? Can we bring our small noticing of how others serve us? Can we notice the turning of a season of dark toward light? Can we capture it in the story of a baby born to an uncertain future?

We take these things, and we add in our willingness to not know, but, maybe, just maybe to hope. And, well, things emerge. A way becomes apparent. A calling of heart to heart. An arc, a direction, and the possibility of putting our hands to work to make something, to turn the world toward something.

And what does it take? What are the small bits? Well, Howard Thurman sang into our hearts the way. He tells us. Plain as plain can be.

To find the lost,

To heal the broken,

To feed the hungry,

To release the prisoner,

To rebuild the nations,

To bring peace among others,

To make music in the heart.

An invitation has been extended. Within the great mystery, if we allow our hearts to open, a way is offered. The door has appeared. It is thrown wide open. We’ve taken, maybe we’ve taken the first step.

Now. Now. It is time.

Make music. Bring peace. Rebuild the ancient devastations. Feed the hungry. Heal the broken. Find the lost.

Join in the great work, the mystical knowing of our intimate connection, and the call, the ancient and ever renewed call to healing. Let us join with Desmond, and Howard, and Martin, all the host of witnesses to a better way.

Let us respond out of the quiet of the day after Christmas.

Into the holy work.

Amen.