A Chikuto Landscape

Glenn Taylor Webb

In classical Chinese landscape paintings, made for nearly 1000 years, the humans depicted in the paintings often are tiny as ants compared to the vast mountains and valleys they are in. Certainly that comparison is true to life. But the paintings teach another truth: their mountain settings made those ant-like seekers of truth (who of course are all of us) grasp the vastness that is in themselves. The painters and even the collectors of the paintings often said so in writing, in notes they added in the margins to mark the moment.

Who were the artists of these paintings? Some of the first in China were court painters, professionals, but the ones I have in mind were scholars, “gentlemen” (紳士) whose birth and education afforded them access to personal development in the arts. They were not just making pretty pictures. They used painting, calligraphy, poetry, music and even public office to bring into daily affairs some element of the deepest truth of life itself. At the source of that truth, at various times in history, the teachings of Daoism, Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism and Zen Buddhism all played essential roles.

The styles of Chinese-style landscape paintings changed over the centuries, in every country influenced by China, like Japan. But their message remained in the hearts of the men who painted them, men referred to as literati (文人). In China itself, between the Communist revolution of 1948 and the reforms of 1980, a flawed truth of enforced equality enslaved the country, and the literati tradition was lost. Since then, the seduction of another kind of truth has gradually emerged in China, the one of wealth. But we still have the paintings.

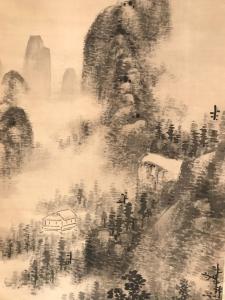

Many years ago, a friend of mine who owned a Japanese antiques store in Seattle decided to close up her shop. She gave me this hanging scroll painting attributed to the Japanese scholar-painter Nakabayashi Chikuto (1776-1853). It was a generous gift whose insurance value even at the time was many thousands of dollars. I had not looked at it for years, but the other day I hung it up and have been admiring it for days now, because it seems to be speaking to (of all things) the political situation in my own country.

Among other reasons, I am writing this lengthy article on why I consider this and other Chinese-style landscape paintings by literati to be a magnificent rebuke of Donald Trump, who comes from a long line of petty tyrants, wizards of self- promotion, who promise (but have no intention or ability to deliver) wealth and justice for all. Here I will just say that years ago, when I was a student of Asian art history at the University of Chicago, under the watchful eyes of Ludwig Bachhofer and Harry Vanderstappen, I made notes on hundreds of paintings like this one, in what is called the Chinese literati tradition. I couldn’t imagine then that the political concerns of the artists of such paintings would reach out to mine. Now I find myself identifying with a thousand years of East Asian literati painters who felt their leaders had moved so far from the truth of things that they had to cry out. Today I am crying out with them.

This painting was made in 1850 by Chikuto, who was born at the time my country began a war for independence from England, and who was looking at the future with fear, at age 74, because my country was coming out of a civil war at home and planning to invade his (which happened in 1853, the year Chikuto died.) There is nothing obvious in his painting that indicates how he was feeling about his government. He is not even painting a landscape that fits Japan’s geography, which has nothing comparable to the great mountain vistas of this painting.

Without ever having set foot in China, Chikuto was merely offering his version of countless Chinese landscape paintings that carry a message of protest from Japan’s cultural source. He was using that model to let us know that he didn’t like what his government was doing. Just as countless Chinese artists had seen into the truth of things and saw how far the latest emperor had strayed from that truth, Chikuto tried to bring the message home. The nation is in trouble, and if nothing else, he is crying out against it with brush and ink in a time-honored design.

To be fair, our situation in the United States at this moment is very far removed from the East Asian situation some 200 years ago, where empires were still in place. American presidents (including Trump) have been held in check because our young democratic republic’s constitution restricts their power. The Chinese Empress Dowager, Cixi (1835-1908), in China, and the last Tokugawa Shogun in Japan, Yoshinobu (1837-1913), had almost dictatorial power. China had its scholar painters then, such as Gu Yun, the “Regarder of Clouds” 顧雲 spent time in Japan but was not as appreciated as his predecessors, or even his Japanese contemporaries. Japanese art historians consider Chikuto to have been the voice of Japan’s literati painters in his time.

It’s obvious to me that I feel as helpless now and frustrated about the distance that my own government has strayed from what I consider to be the truth of things, as someone like Chikuto must have felt about the turbulence of his time. He did not live to see the so-called “restoration” of Japanese sovereignty as a constitutional monarchy in 1868 under Emperor Meiji (1852-1912), but if he had he might have liked it. If for no other reason, it brought Japan into the modern world (even though it couldn’t prevent the Japanese military from trying to take over the world later!

My truth of things has its origin in the ancient Vedic and Abrahamic teachings that produced both Buddhism and Christianity (as well as Hinduism Judaism and Islam.) To put the heart of those teachings down on paper, I would say they are, respectively, “Thou Art That” and “Do Unto Others.”

It has taken me a lifetime to reach the point where my heart has been consumed by those teachings. Now I see that nothing could be further from those teachings than the chaotic, childish, and outright dangerous machinations of the Trump Whitehouse.

But like the peasants of ancient China, who had no choice, many Americans, who have a choice, are following a fool to destruction. And I don’t know what to do. I’ve read all there is to read, in many languages, on the ancient teachings in question, and I’ve done the praying and meditation they require. It is safe to say that for all intents and purposes, I have died. (Yes, Christians, I am saved; and yes, Buddhists, I am fully you.) But I cannot look away. I cannot stop opening up. I will haunt the eons of time and place to protest ignorance wherever it exists. Because it holds all of us back. In both Buddhist and Christian terms, it can be saved, enlightened, removed, and closed down.

The name Chikuto (竹洞) means bamboo cave. For anyone who has seen and walked through the thick, strong, dense bamboo groves that are left in Japan, the name immediately conjures up an otherworldly, dark green, cool, clean, refreshing, protective place where insight can develop. It is also a place where mosquitos and leeches thrive. Just like enlightenment itself.

The name was given to the artist by his teacher as his artist’s name (号), somewhat like the “peace name” (安名) that novice Buddhist priests receive. Chikuto’s teacher no doubt expected his disciple to grow into that cave. To enter it and become it. The Nakabayashis gave their son the name Nariaki (成昌), meaning “to become rich, to flourish,” or more poetically, “to enter clarity.”

I find it interesting that Chikuto used the name his parents gave him often, perhaps to honor them, along with the name he received from his teacher. Both appear in signatures and seals on his paintings. (Note: any beginning student of Chinese or Japanese is taught to see that the first character of the priest-name term (安), for peace, consists of a pregnant woman at home with a roof over her head. Yeah, I know.)

My Chikuto landscape, in the photographs here, shows two Chinese scholars in a hermitage in the mountains. One scholar waits inside the small house in the lower right. The other is coming to visit him, crossing a bridge in the lower left. To me that recalls the times when any person who has gone through the hell I’ve gone through, training in Japanese Zen temples, shares their deepest zazen experience with me, or (in my youth) the times I have spent myself, literally, preparing for a performance of a great piece of music (with or without an orchestra) and a friend who has performed the same piece of music shares their experience with their performance of that music with me. That’s my reference.

When we get together, we will discuss truth. The truth of life in Zen or music. The painting is inscribed with the title of 渓山訪隠 (Keizan Hoin in Japanese), or “Visiting a Recluse in a Mountain Valley.” This is followed by 七十四翁澹老人成 昌寫 (J. shichijushi Otan Rojin Seisho-sha), or in English, “Painted by a Grieving Old Man, the 74-year-old Elder [called] Entering Clarity.” Chikuto’s childhood name, Nariaki, also can be pronounced Narimasa and Seisho, with the same Chinese charaters. Those pronunciations were probably used when Chikuto was an adult. The name Otan (翁澹), translated here as Grieving Old Man, refers to the theatrical masks for old men – known as Okina – which usually are grimacing, as though crying or in pain.

All of these aspects of this painting and its creator resonate with me like shots of adrenaline. Of course I can appreciate how Chikuto takes liberties with spatial organizations of mountains and atmospheric effects that only occurred in Japanese literati landscapes of the 19th century, as well as the methodical brushstrokes that make up the texture of rocks and horizontal blobs of ink that delineate limbs of trees that take on decorative patterns of their own.

But the message that Chikuto’s lovely landscape sends me, of his resistance to social chaos, is embedded in the painting as a whole, assuring me that veterans of deep mental explorations have always brought their insights to the fore, serving the common good, and correcting the lowest instincts of the self-obsessed human animal. In China, three philosophical systems – Daoist, Confucian and Ch’an/Zen Buddhist — fed into the notion that it was enlightened individuals, using everything in their power to explore nature and human behavior, who would point the way to living in accordance with The Way.

This seems in direct conflict with Jewish, Christian, and Muslim teachings – those faiths connected historically to Abraham – that have pointed to a supreme being, the God of the universe, for rules to live by. These monotheistic religions have vied over the centuries with polytheistic religions for the official authority of the rules, from the earlier gods of the ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians, through the gods of the Greeks and Romans. In that sense, the Chinese notion is quite astounding: that human beings themselves have the authority and the ability (albeit virtually impossible to attain) to set the course of perfect human understanding and behavior. In short, that whether one or many gods are in question, they are not needed. Enlightenment is within.

We then can look back in space and time to see that our view of the universe has been split between what we understand today to be East and West – or more accurately, the view from North Eastern and Near Eastern eyes. We don’t usually see things that way today. But we can if we focus on the two places where the religious and philosophical sources for our East and West were born. Then we see vast China casting its influence throughout the East, and the tiny Holy Land of Jews, Christians and Muslims, influencing the entire history of the West.

More simply still, we see people finding ultimate truth in Nature in the East, and in God in the West. Hindu and Buddhist doctrinal histories muddy the waters here somewhat when we take into account the ancient Hindu gods of India, and the Buddhist “deities” in Chinese Pure Land and other denominations of Buddhism, including especially, Tibetan Tantrism. Here we find the exception to the Eastern mind seeing truth in Nature (and landscapes, in this case), and the Western mind finding truth in God (using figural forms to represent both the divine and profane.) All of the Hindu and Buddhist statues and paintings in the world are proud testaments to that exception.

Mountainous landscapes with tiny human figures (or none at all) can be found in paintings from various times in Western (i.e., European) art. But they are rare, whereas they are ubiquitous in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese painting history. Keeping in mind what I have just written in the previous paragraph (Man in the East and God in the West), it is perhaps less shocking to remind ourselves that the subjects of most Far Eastern paintings are indeed mountains, whereas most subjects of Western paintings are people. If landscape paintings are ubiquitous to the East, figure paintings are ubiquitous to Western art.

I’ve tried to account for at least part of why that should be so, without taking on more generalizations than necessary. One of course must be careful not to jump to conclusions about what paintings of any place or age may mean to the artists or to the people viewing them. There is a difference between art history and art appreciation. Some old books on the subject of Chinese landscape painting, written by Western scholars, have missed that difference when they make value judgements about the “originality” of one work or another. But if we look at Chinese-style landscape paintings in general, there are basically two types of landscapes at issue: philosophical and narrative. The message of one is vague, the message of the other is immediately apparent.

The Chikuto landscape belongs to the former, which is by far the more numerous type. Its origins can be traced all the way back to the 7th century, but its closest ancestors are Yuan Dynasty works by artists such as Ni Tsan (1301-1374), whose birth name (倪瓚)

Ni Tsan was from a landowning, wealthy, educated family. As such, he was typical of the Chinese literati painters of his day, who took special pride in not being professional court artists. The Mongols of the Yuan Dynasty had just overrun the country, in the mid-1350s, deposing the last Song emperors and all their competitors from rival Chinese families. Similar but much smaller invasions by non-Han-Chinese had taken place earlier in Chinese history, but this one by the Khans would change China forever. All of the Song Dynasty literati, thousands of whom were magistrates and social dignitaries, suddenly had nothing to offer foreign invaders, even if asked. A small group did help the Mongol rulers learn Chinese ways, and they painted landscapes, but in the “antique” style of earlier times (a style that Ni Tsan made famous.)

Frankly, from ancient times these men considered themselves in touch with what they considered the universe in themselves, and thus far more advanced than illiterate, ordinary Chinese. So how could they do anything but shun Mongol barbarians? Our first real evidence of Chinese literati is with the “Orchid Pavilion Scroll” of Wang Hsi-chih (Wang Xizhi), which commemorates a party he gave in 352, for his fellow poet-scholars. The original scroll is said to have been buried with the emperor, but Wang’s calligraphy has been preserved in stone rubbings that are the model that every Japanese calligraphy teacher I know uses for students to copy.

The party at the Orchid Pavilion was held in a famous garden with a meandering stream running through it. The scroll itself consisted of Wang’s preface and careful transcription of all the poems written by the guests. Servants are said to have set cups of rice wine on trays that floated down the stream, and each participant was to write a poem about enlightenment after drinking each cup of wine. For obvious reasons, enlightenment was sometimes confused with drunkenness. (Indeed, the 8th-century poet Li Po is said to have drowned after a night of drinking, when he jumped from a boat into the moon’s reflection in a river.)

In T’ang times, views of Daoist and Confucian enlightenment were expanded by Ch’an/Zen priests who followed the fierce meditation regimen of the 6th-century Indian Buddhist priest Bodhidharma, whose arrival in China had challenged the Chinese emperor himself. Within a decade the court had adopted the new form of Buddhism as the state religion. It was then that the stories of famous Chinese Zen priests were collected and used to inspire young novices in Buddhist temples.

Technically, all paintings of the Orchid Pavilion story belong to the type of Chinese-style landscape paintings that I have labeled “narrative” paintings. These paintings may contain geographical elements, such as the mountainous setting of the garden, but the stream and poets on its banks in this case, place the story front and center. Another famous story that Chinese literati sometimes paint is the one depicting the “Peach Blossom Spring” that was discovered by a lowly Chinese fisherman. Somewhat like Rip Van Winkle, who lost his way in a New York state forest before the American Revolution, got drunk with a group of forest-dwellers (Indians?) there, went to sleep, and only woke up 20 years later, long after the war was over.

In the case of the Chinese fisherman, he lost his way home in a maze of river routes, only to find a village of happy people living in eternal springtime, with peach trees always in bloom. He, too, lost track of time, but after many years decided to say goodbye and return home. There he told people of the Peach Blossom Spring, and set out with them, hoping to share paradise with them. But he never found it again, and he had to live out his days together with his friends in his old village. The literati interpretation of this story is that anyone may reach enlightenment, a full perception of the way things are (in the peach-tree springtime), but sharing it with others is impossible.

While I was doing my doctoral research in Kyoto, in the sixties, I met many Japanese literati painters. One of them lived near our house, between Kamigoryo Shrine and Doshisha University. His name was Kohno Shuson 河野秋邨 (1890- 1987). At the time my wife and I, and our 4-year-old son, were living in the house of the late great Zen scholar, Abe Masao, who introduced me to Master Shuson (which means “Autumn Village”) on one of our walks. We spent most of the afternoon in his spacious studio, which doubled as a Zendo (meditation hall) for his students. As we left he gave me three of his small works.

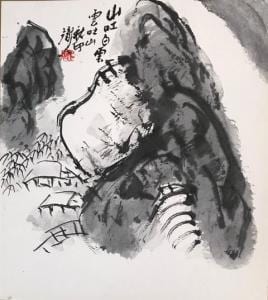

Two of them are landscapes in rich black ink. One has a path on the left, leading up to a plateau between two mountain peaks that soar upward off the border of the painting. Trees and possible shelters dot the lower mountain tops. A pale pink wash on the path seems to indicate where human beings might find footing. The signature reads Shajin Shuson (謝人秋邨), “Grateful Man, Autumn Village” – two names he most often used to sign his works.

The other landscape has almost the same composition, of perhaps the same mountain location up closer. But this time we can clearly identify two shelters on the plateau and a bridge, as well as what may be the top stairs of the path. Most importantly, there is an intriguing title in addition to his names (reversed, in this case, to Shuson Shajin), which reads, “Mountains Reveal White Clouds, Clouds Reveal Mountains” (山吐白雲雲吐山), with “reveal” being a polite way of saying “spit out” or “vomit.”

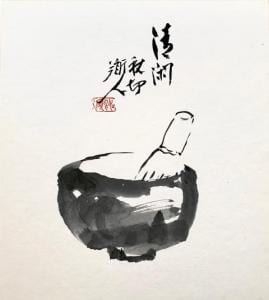

The third little painting, of a Japanese raku teabowl, was done on the spot just for me, urging me to add tea practice to my practice of Zen in Kyoto’s Zen temples. He used the phrase, well used in Japan, “Tea and Zen taste the same” (茶禅同味). At the time (1965) I had no intention of adding the so-called Japanese tea ceremony to my schedule, but in 1970, when I began bringing UW students to Kyoto on the UW study-abroad program, I followed Kohno’s advice.

Sen Soshitsu XV, now retired head of the 500-year-old Urasenke school of tea, recommended teachers for my students. In 1980, Dr. Sen offered to help the city of Seattle rebuild a teahouse in the arboretum, and also offered to train me and my wife and son Reg on the family estate. Thirty years later I became the president of the LA association of Urasenke, a post I now hold in honorary (名誉) status. So I hope the grateful man from the autumn village is listening. His little painting of a teabowl also bears his name, along with a two-character title, “Packed with Silence” (詰閑), with “silence” a euphemism for full awareness.

Up until his death, Kohno Shuson was on the board of the Japanese literati artists association. After assuming my post in the School of Art at the UW, I arranged for Mr. Kohno and his fellow artists to have an exhibit in Seattle on the university campus, in August 1978. Fifteen of them came, each sending one of their works in advance with information that I included in a catalogue. The men spent a week at a nearby hotel, at their own expense, and I enjoyed taking them different places, where they sketched everything in sight.

Unfortunately, one of them, Master Tsukiori Shinko (月居宸光), had his passport stolen from his room. It took another week, after the others had returned to Japan, for it to be replaced. So he stayed with us in our home in Redmond, which had a backyard that looked out on a dense forest. His full name means something like “Moon-Dwelling Emperor of Light” and as such, he spent many hours painting the forest, the moon, crickets, and a wildly blooming bush-clover in our garden that he said reminded him of Kyoto.

As for my landscape painting by Chikuto, the sight of it always makes me think of a former UW student of mine, Kawasaki Kazuhiro (who went by “Hiro” then, as he still does.) Hiro was in the graduate program in Japanese art history, and one of the students I challenged to work with me on a wonderful collection of Japanese paintings that a former teacher of mine in Kyoto, the late Mori Toru, had helped gather for the Fred an Isabel Pollard Collection in the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, in British Columbia. For months my team worked on English essays that would help visitors understand what they were looking at. We piled onto the ferry that took us over to Vancouver many times. It was a wonderful time.

The catalogue – JAPANESE ART — was published in 1972, under my name and the names of John Vollmer and Colin Graham, of the Royal Ontario Museum and the Art Gallery, respectively. My students, besides Hiro, were Jin K. Lee, William Rathbun, Mark Sandler, Yuri Takahashi, and Carla Zainie. The articles they wrote bear their initials. I just read them again, and they are even better than I had remembered.

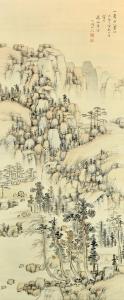

Sadly, I have lost touch with most of those students, two of whom (Mark and Yuri) are dead. But when I started looking at my Chikuto landscape the other day, the first person who came to my mind was Hiro. So I called him at his old number, and it worked! After explaining why I was calling, we talked about the catalogue. Hiro wrote six catalogue entries, including one on a landscape painting by Chikuto. He mentions that Chikuto painted this work (No. 21 in the catalogue) in the autumn of 1842, in the manner of Huang Kung-wang (1269-1354), who like Ni Tsan is considered one of the great masters of the literati painting tradition in China.

Unlike my black-ink-on-white-paper Chikuto, the Victoria Gallery Chikuto is almost colorful, with a pale yellowish caste to the paper, and pale pink and blue washes accentuating block-like shapes of boulders that (in Hiro’s words) “pile up and merge together to produce a quivering effect across the painting’s surface.” The lighter touch of the brush strokes also adds to the overall “unstable and almost transient quality” of this painting when compared to the robust brushwork of my Chikuto. The lone human figure waiting in the open thatched hut in the right is invisible until scrutinized closely, in contrast to the almost cartoonish figures in my painting.

Still, for all their differences, I find these two paintings to be more alike than not. I see them as I would two performances of the same piano concerto by two different pianists, their interpretations dependent on their feelings at the time, and maybe on the attention of the people in the audience. Painters and musicians alike must do what they do best to protest the utter ignorance of the misbegotten world they find themselves in, a world that in spite of everything, is of their own making. But I am not so naïve as to believe the efforts of artists can really change the direction of history.

As a matter of fact, none of the masters of the arts in the history of the world have been able to do that. Chinese literati painters, as strong as their expressions of displeasure with their government were, could not hold back or change their Mongol, Manchu or Maoist opponents’ policies. And the glorious music of German composers not only did not stop Hitler, it was appropriated by him and used against them. But we live in a different time. Revolutions have gradually produced democratic governments of various construction, which have been able to actually dismantle dictatorships. We seem to be forgetting that.

Looking at these old paintings has taught me many lessons, including some that came from my own interaction with the people now as well as then. In my old age those lessons were surprising and maybe the only ones that matter. Life is miraculous. But the political activism that is available to me now, and to all Americans and people of other nations who will stand up for democratic values, must not be squandered. I see those values, which I consider to be as close to ultimate reality as anything else, being squandered by people who say we cannot do anything.

We should criticize Christians for supporting Trump’s anti-Muslim stance; we should call anyone out who tolerates Trump because he thinks women who have abortions “should be punished” or who applies ancient Near Eastern laws that tell slaves to obey their masters and condemns homosexuality. The Japanese attitude of “nothing can be done” (shoganai), may seem like Buddhist doctrine. But it is not. It certainly did not prevent the militarization of Japan in the 1930s. Similarly, some Zen students today, whose mistaken view of emptiness has robbed them of their voice and ability to act, are infected with helplessness. This is wrong. This is not using skillful means. This is not compassion. This must not be the direction my world takes before I say goodbye.

***

Dr. Glenn Taylor Webb was born in Lawton, Oklahoma in 1935. At the age of 3, he started learning classical piano, which he continued, reaching the highest level of national competition. He studied in New York with Julliard teachers and gave recitals around the country, until the age of 17. During one of his recitals in New York, he met Daisetsu Suzuki, who first brought Zen Buddhism from Japan to the West. Dr. Suzuki’s world view inspired Webb’s interest in Japanese studies and religious studies.

Dr. Webb attended Abilene Christian University in Texas, where he met and married his wife, Carol St. John. He graduated with a BA in Art and Religion in 1957, after which he was a graduate fellow for a year at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Supported for the next 7 years by U. S. National Defense Foreign Language grants, he studied Japanese language and culture in the Art History and East Asian Studies Program at the University of Chicago, where he earned a Masters degree. In 1964, Dr. Webb won a Fulbright Scholarship, which allowed him to pursue doctoral work at Kyoto University for two years. There, Dr. Daisetsu Suzuki, whom he had met at 16, became his mentor, along with other prominent Japanese scholars. Webb additionally trained in Buddhist temples to gain a deeper understanding of Buddhist teachings and was even ordained in the Rinzai Zen priesthood. Along with his wife, Carol, he also began studying Urasenke chanoyu, and they both became accredited instructors. After returning to the States, Dr. Webb earned a PhD in East Asian studies from the University of Chicago, with his dissertation entitled Japanese Scholarship on Momoyama Culture.

In 1966, Dr. Webb began teaching full time at the University of Washington’s School of Art and Jackson School of International Studies. He co-directed the Center for Asian Arts and promoted cultural exchange between the United States and Japan. One of his projects was running the Kyoto Program, wherein University of Washington students studied in Kyoto under the foremost figures in Japanese traditional arts. In 1970, Dr. Webb published his first book, “The Arts of Japan – Medieval to Modern,” based on the work of renowned art historian Seiroku Noma. To further students’ study of Zen and chanoyu, Dr. Webb established the Seattle Zen Center, which is still in operation today. He also worked to incorporate the study of chanoyu into the curriculum of the University of Washington, laying the first foundation of today’s vibrant chanoyu community in Seattle.

Dr. and Mrs. Webb moved to Malibu, California in 1987, where he undertook the directorship of the Institute for the Study of Asian Cultures (ISAC) at Pepperdine University. While there, Dr. Webb invited many leaders of Buddhist groups, including the Los Angeles Zen Center and the Jodo and Nichiren Temples to speak at Pepperdine. He also invited the Bukkyo University in Kyoto to bring its students for visits to Pepperdine’s Malibu campus, promoting the cultural exchange between Japan and the United States. Even after his retirement in 2004 and his move to Palm Desert, Dr. Webb has continued to maintain a strong connection with Bukkyo University in Kyoto and Los Angeles, in which he serves as academic advisor and visiting professor.

Finally, as Emeritus Professor, Dr. Webb maintains a relationship with Pepperdine University, and both of the Webbs have been actively involved in the Urasenke Tankokai Los Angeles Association since they moved to Southern California. After serving as a president for 12 years, Dr. Webb is now the association’s honorary president. But the true legacy of Dr. Webb’s career is found in the large number of students he has touched – in both Japan and America – during his 50 years of teaching.