Stop that War on the other side of the River.

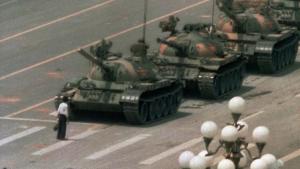

Seventy-three years ago, Monday, the 6th, the American military dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, today, the 9th, a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

Today, we are shadowed by the anniversaries of these bombings of Hiroshima & Nagasaki. There are those who say it quickly ended a war that would have lingered in a terrible, terrible way, costing perhaps millions more lives. Others say this was too much, the Japanese were already preparing to surrender. And it should never have been done.

I have no way of knowing what was right. I cannot imagine the responsibility weighing on those who had to make the many decisions along the way. What I can know is that it was something beyond horrific. That new kind of bomb opened a new era – an era where the dream of apocalypse, of a life-ending horror was now within our human grasp.

Me, I grew up in the shadow of mutually assured destruction, giving us perhaps the most accurate of all acronyms: MAD. Me, I vividly remember duck and cover

Perhaps the most useless of preparations for atomic annihilation – and obvious to me very, very early on. I believe that was true for my entire generation. Most of us. Most of us, for sure.

And. And. With that, what about war, that most ugly of our human occupations? And. What about peace, that most elusive of human longings? And, maybe most of all. What about our place in the great play of existence, our real existence within this world within our bodies, where there is no option to sit it out? We live in a world with no escape. So. So. How do we live our lives where every choice has a consequence, has cascades of consequences?

Yesterday one of us and I were talking about the American spiritual figure Ram Das.

My friend used the word holy to describe him. There’s no doubt that can be a right word. Some years ago, I attended a small conference of teachers of Buddhist practices in the West sponsored by the Dalai Lama. Our guest of honor was Ram Das. The people who wanted to get pictures with him, or simply autographs, which was hard because he’d recently had a stroke, were mostly Tibetan monks. Not so much convert monks, but the Tibetan Tibetans. Among the many things he’s been involved in over the years Ram Das was a principal in broadcasting the work of the Seva Foundation, helping them to raise the money that has restored vision to, at current count, about four million people. Holy. Not a bad word.

But, I wasn’t completely content with the term holy. Ram Das was always been someone dancing at the edge. His first incarnation was as a Harvard psychologist and collaborator with Timothy Leary in his quest to save the world through psychedelics. Later Ram Das would get caught up in a number of problematic projects including a spectacularly absurd pyramid scheme that he thought would make everyone, including him, rich. But, and, this is so important, he never hid his mistakes or even his wandering into dead-ends, he never tried to present himself as anything but a seeker and with that a doer. He screwed up. And he did good.

So. Holy. Sure. He has grown ever more transparent, ever more authentic. But, even more, he became what I want to call a human being. I think the Yiddish is mensch. Actually, that’s sort of the reason Ram Das was invited as a special guest at a conference of Buddhist meditation teachers. He was even designated if informally by no one less than the Dalai Lama an honorary Buddhist.

Foolish and holy. Human. Mensch. And with that war. And, peace.

I believe within that are pointers for us in this terrible and beautiful planet, so wounded, and so lovely, among us, human beings, so dangerous, and, and, so beautiful.

In 1993, on the one-hundredth anniversary of the World Columbian Exposition’s Parliament of the World’s Religions, a second parliament gathered in Chicago. I’d recently began serving as parish minister at the Unitarian Church North in Mequon, Wisconsin. And when I read about this I seriously considered attending. But, it wasn’t a really good time, and so I passed on the opportunity. It became one of a small list of things that I didn’t do that I really wished I had.

One that lingers was a chance to meet Rasuptin’s daughter. The other missing an opportunity to meet the Dalai Lama, actually that happened twice. So, smaller and bigger. This one I think fits sort of in the middle of that little list of regrets for me.

The official highlight for many was an address by the Dalai Lama. But for me, the most important thing to come out of that gathering was a document, “Declaration Toward a Global Ethic.” The principal author of that document was the Rev. Hans Küng, a Roman Catholic priest and scholar.

I once heard Küng, a controversial figure within his community, described as the Catholic Church’s finest Lutheran theologian—which is, perhaps, a way of acknowledging that he is one of the ecumenical Christian community’s finest minds. That document was signed by two hundred religious leaders, among them fourteen Buddhists, including Professor Masao Abe, the Zen master Seung Sahn, and this Holiness, the Dalai Lama.

It asserted there are “four broad, ancient guidelines for human behavior which are found in most of the religions of the world,” which it listed as “irrevocable directives” for those who would find peace for the planet.

These are important:

These irrevocable directives are: (1) a commitment to a culture of nonviolence and respect for life; (2) a commitment to a culture of solidarity and a just economic order; (3) a commitment to a culture of tolerance and a life of truthfulness; and (4) a commitment to a culture of equal rights and partnership between men and women.

I’m deeply moved by this analysis, which I think cuts through the fog of the conservative part of religions, that part which is meant to sustain and transmit a particular culture—defining inside and outside, us and them—and which is so often used as a club to beat people into conformity. Instead, the directives point to the radical heart of pretty much all religions, that part which opens us to the finest of what it means to be human.

The first of the directives, the first grand intuition of our deep humanity, is that in spite of our natural proclivities to violence, there is a better way, and we can live into it. The second tells us we are genuinely responsible for each other. The third points to our need for broad tolerance, which is found within our commitment to genuine honesty with ourselves and with each other. And, finally, the fourth—so buried in so many religions, but implicit at their heart—reminds us that women and men need each other and can only heal from the wounds of life when we see we are all in it together as equals. I would add that the issues of sexual minorities are bound up with this last assertion, inevitably, inextricably. And, out of our turning to examine the depths of our human sexuality within the terms of seeking justice, in many later adaptations the language is in fact tweaked to be less binary.

These four directives offer a life of authenticity and truth and a way of healing for hearts and a world torn by strife. For me there’s a next step that takes this document and its four irrevocables from ink on paper (or pixels on a screen) into our actual lives. There is a Japanese saying, gyogaku funi, which means “practice and study are not two.”

And it is here I find myself thinking of the American Zen teacher Bernie Glassman. Bernie is one of those characters who steps on the scene, and after they pass through, everything is a bit different.

He originally was meant to be a rocket scientist, earning a Ph.D. in applied mathematics from UCLA. And he did some of that rocket work. While at grad school, however, he met the Japanese Zen missionary Taizan Maezumi. Eventually Bernie became the Japanese Zen master’s first American Dharma successor.

He would go on to have an unconventional Zen career. At first, he was a pretty conventional Zen priest and teacher. He gained a reputation as an insightful guide. But then from the outside rather unexpectedly he dropped the priest part. He went to clown school, put on a red nose and called on people in the Zen world to lighten up a bit.

From there he went on to various social justice-oriented projects, including the Greystone Foundation, a Zen center that has evolved into a social service agency focused on the needs of the homeless and hungry. He has also been deeply focused on issues of peace and peacemaking. As of today, it has been a couple of years since he, like Ram Das before him, suffered a debilitating stroke, but he continues to stand as a shining example for us all. Holy? Yes. Human? Oh, yes. And lots and lots of mistakes come with that territory, in case you haven’t noticed. Mensch? You bet.

In service to that goal of service Bernie and his late spouse, Sandra Jishu Holmes, took those four irrevocable directives from the World Parliament to heart and created what is now called the Zen Peacemakers. Along the way he reframed the directives as four commitments. And they’ve caught on. I would say most people aware of these four things in fact think they came from Bernie’s fruitful heart. It does appear that it has been our Western Zen communities that have most integrated those calls into our own lives as integral to our spirituality. My own Zen communities Blue Cliff Zen and Boundless Way Zen, which have no direct connection to Bernie, have incorporated these commitments into the vows we take when we formally undertake a spiritual life.

Vows. I hold up vows as something we might all consider. Promises to ourselves and to the world.

As the leader says in the ceremony of commitment for our Zen community, “The wheel of the Dharma turns and turns. Each generation manifests the great way. Today we commit ourselves to the way of awakening, manifesting as peacemakers in a world torn by strife.”

It’s time to step up to the plate. It’s time to do things. It’s time to notice what’s what and to choose, how will I live? Then, for us, in the ceremony for those who have chosen the Zen way, and the way of the peacemaker, the new initiate responds together with all those who’ve made the commitment before,

“I commit myself to a culture of nonviolence and reverence for life; I commit myself to a culture of solidarity and a just economic order; I commit myself to a culture of tolerance and a life based on truthfulness; and I commit myself to a culture of equal rights and partnership among all people.”

So, what does this look like in practice? What is an example of how this might be engaged? There are areas of profound concern that are not mentioned directly in those vows, but are intimately part of the vow. For instance, I think of the Black Lives Matter movement.

What about those who witness the injustices, the endless injustices perpetrated against people of color and particularly black Americans, and who do nothing? How easy is it to just say “all lives matter,” and wash our hands of the deep complexities where in reality some lives matter less than others.

So, yes, if you’re wondering, I believe all lives do matter. Ultimately that is the point. But, taking the vows, and looking closely, then what? Can we look at what is happening in our country and really say that black lives matter here? A hard question. Lots of hard questions on an authentic spiritual path. And. So. Me, I find those words so important. Black lives do matter. Again, yes, without a shred of hesitation, it’s hard for everyone. This is not a good time to be poor and white in North America. It’s never been particularly good to be a woman here. And gay or lesbian, or transgender? People still die just for being LBGTQ. And, yes, all racial minorities suffer in some degree. And without diminishing that truth for a moment, there is a terrible historic injustice around black and white.

And my heart breaks when people who have had the boot on their necks cry out “black lives matter,” and when I hear “all lives matter” in response. Sadly, mainly, I hear Pilate asking, “What is truth?” as he washes his hands of that particular mess.

Perhaps these are hard words, but perhaps sometimes we need hard words. Authentic spirituality is not a balm for our egos, it is a balm for the hurt of the world. And of course, there are those ecological concerns. If they’re not addressed, pretty much the rest probably don’t matter. But they fit right in. Facing in we find our place.

And with that the spiritual point. And the point of spiritual practices. The message at the heart of all these presentations.

The message hard and true:

We, all of us, you and me, and everyone and every other creature on this planet are related.

All the other things about us contending on behalf of ourselves and our own is true, but we forget the real extent of who is “ours.” In fact, we are all of us family. We are one. We are all children of this planet; the earth is our mother. Her blood is our blood.

And this is not just philosophy, words unconnected to our real lives. It is a truth we know in our bones and marrow. But it is a latent knowing. We often forget it in the headlong rush of our individual needs, the immediate situations we find ourselves in. This is why spiritual practices. This is why we need, desperately need to take up the disciplines of the heart that return show us this is not philosophy, this is our reality, on the other side of the stories we tell ourselves of separation there is the truth that we are connected. And. Forgotten or not, we are all deeply connected. We just need to remember this truth. If we do, we change our behaviors.

It is like we’re drunk on the short term and the immediate need. But we are capable of sobering up. And the sober truth is, we are related. This truth haunts our dreams and informs our religions at their deepest places and is the great source of that sense of fairness we feel in our bones, even if we are capable of violating it. Our immediate task is to sober up, to remember, to re-member, to look into our hearts as well as our minds and to find this truth of intimacy as the deep truth, as your deep truth, as mine.

The question for Zen and its communities in the West is just like the question for Unitarian Universalists: what do we want to be? For some our spiritual traditions have an element of a hospital, a place of healing in a world of hurt. For others, our traditions are a nursery where we are sheltered and can grow. But. If we aren’t careful we will simply be a hospice, a place of care as the world dies.

I hope not. I believe the possibilities of what we find among us are vast. We can be beacons of light in a world in danger of being lost to the night.

So long as we turn the light inward for a bit and notice who we really are.

And here Bernie is important. Really important. Like with Ram Das and a host of others, Bernie’s gift to us wasn’t just grabbing these four insights and pitching them to the world, but rather finding a clear, if not easy, path to their realization.

Study and practice as one thing. He took something from the standard Japanese-derived Zen initiation ceremony, called the Three Pure Precepts, and reframed them as guidance for people of any and perhaps of no spiritual tradition, inviting us to plunge into the unknown, to bear witness to the pain and joy of the world, and to strive to heal oneself and the world.

Not knowing.

Bear witness to the pain and joy of the world.

Strive to heal oneself and the world.

The call is to become peacemakers. For those of us who’ve embraced a spiritual path, we are, I genuinely believe, challenged to embrace the way of peacemaking. Each in our own way. But, all of us called to dig deep into the matter. We are all called to engage the questions that flow out of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And, in that, to not rest with some facile answer. To accept the horrors of choices and to engage with consequences and to see how we, each of us, must take stands.

There are no guarantees. Well, one. We will all of us die. The question, the only real question, is how shall we live? To what shall we devote our attention for this brief moment we call our lives, my life? To what shall we give our lives?

Is your choice to be a healer, to be a peacemaker, to join the caravan of hope and possibility?

If so, let me repeat the method: Plunge into the unknown. Bear witness to the pain and the joy of the world. Strive to heal oneself and the world. I think of the first two as invitations into the very heart of life; the third—healing, for myself and for the world—grows out of them as if through a secret alchemical formula. Plunge into the unknown, bear witness to the world’s pain and joy, that you may bring healing. This is how we become peacemakers.

The Koan:

Stop that War on the other side of the River.

Here we are in a time shadowed by those terrible events seventy-three years ago. And, actually, war or threat of war or rumor of war is all around us. We live in violent times. We are, frankly, a violent species.

So, how might Buddhist wisdom be helpful for us as we seek out ways to be of use, to be, perhaps, even, peacemakers?

For me the most important thing is that we don’t have to win. In fact, of course, we all die. No matter what we all die. What matters is how we live. We have the power within our hands to make our lives a curse for ourselves and others, or a blessing. Within the mysteries of our lives, our human lives, we are given the opportunity to discover currents of connection that can make our actions healing, a blessing for this world.

Our choice. Yours. Mine.

For the sake of the world, may we choose wisely.

Questions:

What can one person do in the face of war?

What is my responsibility for something I didn’t personally do?

What do I think of the call to be a Peacemaker?