I’ve been thinking about the various comments about Zen meditation I’ve seen around the inter webs. Some of those comments are quite helpful. Some are beautiful and provide authentic direction for people on the way, including me. Others not so much so. Too many, I fear, seem to simply offer mediocre paraphrases of the texts of preferred ancestors without much nuance. And some are simply offering salve for egos branded as “Zen,” but having no connection to our practice and its healing of the great hurt.

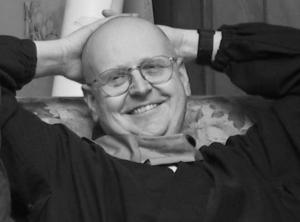

As I was ruminating on that mess which is our current public conversation around Zen practice, I recalled Kyogen Carlson and how clear and practical he was as a Zen teacher. If you don’t know him, Roshi Carlson was one of the premier American Zen teachers at the end of the twentieth century and into the first decade and half of the twenty-first. He and his spouse the Zen teacher Gyokuko Carlson founded Dharma Rain, one of the leading Zen centers on the American West coast.

His book Zen in the American Grain: Discovering the Teachings at Home has, sadly, long been out of print. What I especially liked about that book was when the roshi addressed Zen meditation. it was at once well informed by our tradition, and represented a fully engaged and profound personal practice. He knew of what he wrote. And I thought those passages particularly useful for anyone wishing to dig into the deep mater that is zazen, Zen meditation.

And so, here I offer a lightly edited selection from the appendix to his book, “Notes on Zazen Practice.” For the whole essay, and more on the Zen life, I recommend seeking a copy (abebooks.com is often a useful resource for out of print books) and reading it.

Roshi Kyogen Carlson points the way for all of us…

(I apologize for the typos in my transcription. I’ll try to fix them over the next day or so…)

Notes on Zazen Practice

Kyogen Carlson, Osho

During my years of teaching meditation and answering questions form those newly engaged in zazen practice, I have notice several questions that are quite common, coming not only from beginners, but also from people who have been practicing for some time. I would like to share these questions and some answers in the hope it may be of benefit.

Every so often someone will tell me that he has been sitting for several years but can only manage full lotus for a short time, and that even half-lotus becomes too much to bear after thirty or forty minutes. He will go on to describe pitched battles with ego as the time to sit approaches in which every excuse imaginable not to sit presents itself. Then he may ask for some advice on overcoming the physical and mental resistance he is experiencing.

Here we have an excellent example of someone pushing much too hard just to conform to an ideal of what Zen practice should be. Even if you are sitting on a bench or chair, if this description sounds overmuch like you, please be more gentle with yourself. Turning the flow of compassion within begins with treating your body with respect and care. It is neither necessary nor wise to strain to maintain any posture, and signs that you are pushing too hard should not be ignored.

We have been given an aversion to pain for a very good reason. If the body is sending signals that something is wrong, we set body and mind against each other when we grit our teeth in stubborn refusal to give in to it. Of course, it is good to make an effort to improve our physical ability to sit, but zazen should never become an insurance test.

If we approach zazen with gentle determination and a bright mind, we will look forward to sitting with eagerness. It is really terrible, and completely unnecessary to face meditation with dread. Too much rigidity in practice makes it joyless, and when it is, people either drift off to other things or become joyless themselves.

Dogen says we should sit in a way that is natural joyful,(1) and so it can be. When it is, zen remains a practice that will enrich us all the years of our lives. I always recommend sitting for as long as is comfortable in a given posture, then making the effort to sit a little while longer. After that, change to another position, or do walking meditation for a few minutes, then resume sitting.

Meditation done well for five or ten minutes is far superior to hours of self-torture, so please done’t strain to achieve an ideal form, and please don’t be in a hurry to progress physically, for you’ll defeat the deeper purpose of zazen. The posture should be so still, centered, and comfortable that th mind is alert and completely relaxed.

I remember how surprised I was to discover that the lotus postures are recommended precisely for their comfort, and also because the postures are a physical expression of what we are trying to achieve in meditation. Sitting in full- or half-lotus holds your hips in a position that makes your back naturally erect, because it places your shoulders directly over your hips.

This forms a vertical axis right through your upper torso, so that you feel physically centered. This is also a posture of great awareness, just lie when you sit on the edge of your chair at the climax of a movie. In zazen this principle is applied in reverse; by holding ourselves erect, we very easily remain alert.

Further advantages include the triangular formation made when we sit crosslegged, which gives great lateral stability to the posture, and the way the position of the hips gives stability front to back. This stability helps us to remain extremely still without conscious effort to hold ourselves upright. Since we are not reclining against any surface, our circulation is not impeded and there is no need to fidget. In this attitude of still, alert, centered comfort we find the essence of meditation to which tortured endurance bears no resemblance. So, although there is good reason o want to develop the ability to sit comfortably and regularly on a chair or kneeling (which lack only the lateral stability of crosslegged postures) and gradually work into Burmese or one of the lotus positions when and if it feels right.

The question of how hard to push in meditation also comes up with regard to the length of time we spend doing it, regardless of posture. People these days are very busy, and it seems as though there are more demands on our time than there are hours in a day. It is bad enough when the mind wanders and we gt restless and start to fidget, but it is worse when we feel the call of half-a-dozen things demanding our attention. You can almost hear the clock ticking in someone’s head when that happens.

The problem arises partly because we try to separate the time for meditation from everything else we do. There are many times that this is actually very good to do, but not when it creates conflict in our own minds about what we should be doing. Just as trying to conform to an ideal posture can set body and mind at odds, so can trying to conform to a set time of day or duration of time for meditation practice. If you don’t decide ahead of time that you are going to sit for twenty or thirty minutes, you can bypass the issue of “budgeting time.”

If this has been a problem for you, try sitting without any predetermined length of time in mind. Decide that you are only going to sit for as long as it feels good to do so. it is so much easier to begin the practice when you can’t fail to meet your “quota.” As you relax more deeply into sitting, time goes by very easily. Sometimes you will sit for just five or ten minutes, but you will have done so wholeheartedly. At other times, time will slip by and you will realize that for that day, the twenty or thirty minutes was very well spent. Some days you may fin that the urgency of other demands is such that you really should be doing something else. So, realizing that, off you go.

What I am describing here is a way of letting the deeper mind set your meditation timer for you. It is also a way of harmonizing your price with all the other things you need to be doing in your life, rather than pitting practice against everything else. This is why very busy people find coming to the zendo here at the Center all the more important.

Once here, a block of time has been committed to the practice. The bells and gongs are in the hands of the time keeper, and the schedule for sittings and services are set for the benefit of all attending. Sharing practice with other people makes the time spent a mutual contract between all those there, so it becomes something shared. Rather than just taking time for ourselves, we are also giving to others, and this makes the practice easier to do.

When to sit can be as difficult to work out as how long to sit. Once again, for busy people with many demands on their time, flexibility within a firm commitment is very important. We once worked with a professional couple with two small children. They were a classic example of very heavily committed people, with unending pulls on their time. At one point, they realized they could tie their evening zazen schedule to their children’s bedtime. They would sit as soon as both children were asleep, a time of profound quiet, I was assured.

They made a promise to each other to do this for a specific period of time, say three month, except when they had guests, or when their children fell asleep after a specific cut-off point, in which case they let it go for the evening. This way they were committed to regular practice but did not set the practice against the other things they needed to do.

….

Another question that often arises has to do with how to handle the many thoughts, emotions, memories, and such that can be so distracting during meditation. I have found that people can vary quite a bit in the types of things that arise to distract them. One person may be appalled to discover the first time she sits that her thoughts rampage through her mind like a runaway train. Another may find sitting fairly easy and pleasant at first, but a little later discover that whatever emotion is uppermost in his life at that time becomes intensified and almost unbearable during meditation.

Let us first consider the case of runaway thoughts. I have heard descriptions of monumental battles people get into when trying to control their thoughts. While we should not let oursleves be carried away by distracting thoughts, sometimes called Monkey Mind, we do better to accept them gently, compassionately, and wholeheartedly.

We should start by embracing our own tendency towards Monkey Mind patiently, as one would the prattlings of a small child. There is nothing wrong with having an active mind, only in making it the center of your being. The stillness of meditation lies beneath the chattering of the thinking mind, not beyond and separate from it. Have you ever been sitting in meditation and suddenly realized you have been a hundred miles away for th Elat 20 minutes? “Oh no! Now I have to start over,” you may think. Or, perhaps you will bear down extra hard to make up for lost time.

But the moment you realize that you have drifted off somewhere, you are, right at that moment of recognition, meditating perfectly. What could be added to this awareness? By gently accepting Monkey Mind, it is conquered, and the habitual prattling of thougths we have grown so accustomed to will gently subside by itself.

People have told me that when distracting thoughts seem especially persistent, they will sometimes break the train of thought by a process something like mentally “blinking.” I think it can be good to do this occasionally if it is done to help grab the will but be extremely careful of making a practice of repressing thoughts. At one time in my own training, I became very good at repressing thought altogether, thinking that “emptying” my mind had something to do with the “emptiness” mentioned in the sutras. Then one day during a meal I suddenly lost the right side of my vision. Everything to the right of a place extending directly out from my nose simply vanished. My vision gradually returned, but it was these very disturbing several minutes that brought a clear message to relax my practice.

My feeling is the when distracting thoughts persist, one of the best ways to handle them is to count your breath. This is done by counting each breath as you exhale, breathing slowly and deeply, but naturally. When you get to ten, start again at one. It helps to know there is a difference between awareness, or consciousness, and thought. By being aware of your breathing, you become aware that your consciousness goes far deeper than the thinking process. As you focus awareness on the still depths beneath thought, the thoughts will subside by themselves, simply because you stop investing energy in them.

As you do this, you are learning to “live” in a place deeper than your own head. In time, you will feel a “settling” of body and mind, a relaxation into meditation. As this settling continues, it can help to stop counting your breath and simply follow it; the is, to watch each breath come in and go out without counting. As the relaxation becomes complete, you can let go of following the breath and concentrate on “just sitting.”

From here meditation can take many forms, some extraordinarily deep, some ecstatic, some less deep but very meaningful. It is important not to expect anything but to simply prepare yourself for whatever experience is to be given. After all, it is a gift, and not something that can be achieved or taken by force.

Just as it is with distracting thoughts, so it is with any other problem that arises during meditation, whether it is intense emotion, feelings of inadequacy, resistance to the teaching, or daydreaming. Since meditation is a process of gettin beyond self, all the ways in which we cling to self stand out in sharp relief as we progress. It can help to realize that increased awareness of our own attachments is a sign of progress if we are willing to learn from it. But always it is through gentle acceptance of our limitations that we deepen our awareness of the buddha nature. The very thing within ourselves that recognizes and accepts these limitations is our own deeper mind, our own buddha nature, so there is nothing else to be done.