One of my favorite spiritual books is Thomas Merton’s translation The Wisdom of the Desert: Some Sayings of the Desert Fathers. It’s a selection of stories from the Verba Senorum, telling of hermits who lived in the fourth century Egyptian desert on that fertile cusp between antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

I read the book first early in my Zen training, and have a copy filled with marginal notes that I made at the time. I am embarrassed at some of my thoughts at the time. And, at the same time I see the foundations of a spiritual life being worked out.

As a child of the West practicing an Eastern religious tradition, how can I not bring some of the gifts of my natal tradition along for the ride? Some of those things are hindrances to advancement, I suspect. Some lead to misunderstandings. And some are part of a personal synthesis that has shaped my life.

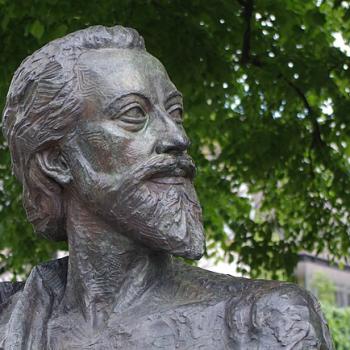

Sort of like, as I see it, in Thomas Merton’s life. We can see him drawing upon the wisdoms of the East, particularly Buddhism on full display in his little book the Wisdom of the Desert. There are more scholarly translations of the Verba Senorum. Most people seem to cite Helen Waddell’s work as particularly good. And I’ve dipped into several of these. And doing that I see how Merton’s version is cut in some ways to serve his particular stance – that place where East and West meet.

And that’s precisely why I continuously return to Merton. He seems pretty obviously to have what in Zen circles is sometimes called the “eye.” He has a deft touch and a sense for what might actually help us today as we attempt our own path toward wisdom. And so that little book has become one of my constant companions over the many years.

I’m so taken with this collection that I’ve cited one passage or another in my Monkey Mind column any number of times. Here’s another.

One of the Fathers told a story of a certain elder who was in his cell busily at work and wearing a hairshirt when Abbot Ammonas came to him. When Abbot Ammonas saw him wearing a hairshirt he said: That thing won’t do you a bit of good. The elder said: Three thoughts are troubling me. The first impels me to withdraw somewhere into the wilderness. The second, to seek a foreign land where no one knows me. The third, to wall myself into this cell and see no one and eat only every second day. Abbot Ammonas said to him: None of these three will do you a bit of good. But rather sit in your cell, and eat a little every day, and have always in your heart the words which are read in the Gospel and were said by the Publican, and thus you can be saved.

Merton includes a small footnote to that passage about the words said by the Publican, “Lord have mercy on me a sinner.” These will eventually morph into the Eastern Christian mantra practice that includes variations on that phrase. “Lord Jesus, have mercy on me, a sinner,” “Jesus, have mercy on me,” and often simply, “Jesus.” it’s an ancient practice and quite powerful.

I’m deeply intrigued by this anecdote, which can even be thought of as a Christian koan, that is a statement about reality and an invitation to manifestation. Although the fact that it is presented as practical advice can confuse the “koanic” element. I suggest first take it as some sound and quite practical advice. At the end of this little piece, I’ll return to the koan part.

With that on to that first part. I love that the sage suggests the motivations that led the monk to that cave and the hairshirt were wrong, or perhaps more accurately not sufficient to win the goal. I suspect most of us take on the spiritual path for reasons that make less and less sense over time. Certainly has been true for me. My motives at the beginning of my spiritual life are not completely gone, but they no longer drive my way on the path.

Of course some of our wrong motives are more compelling than others from the get go. Needing to relax is hardly ever a sustaining motive for taking on a spiritual discipline. (They’re usually just too hard, and watching a sit com for half an hour does that trick without all the bother.) Wanting to understand the hurt around my mother’s death is stronger. And my brother’s. And my son’s. And, as I age, facing my own. But, ultimately, every story becomes a little too much, and we need, it appears, to put down that load and continue with empty hands.

But rather more important I think, after the abbot’s suggestion that extreme asceticism isn’t going to do it, either; he outlines three things. I suggest these three things might be useful for any of us who are looking for an authentic spiritual discipline.

So, number one, is to sit quietly. I suspect this is the universal solvent of the spiritual way. It doesn’t take special robes or equipment. Just sit quietly. I would add it seems important to do this regularly, perhaps daily, and to give it a little time each day. Unpacking what “sit” really means, and I would add what “quietly” really means is the stuff of the practice.

Number two is that, “eat a little every day.” The real path appears to be one of moderation. Too little is as bad as too much. I suspect this extends from our choice of eating habits to our choice in clothing and on to the whole range of our lifestyle. A harmonious, simple way does appear to be the stuff of that authentic spiritual path.

And number three, finding a way to open your heart. And, equally, open your mind. There are many ways this can be done. However, despite what you may have heard, not all paths are in fact equal. Be enormously careful. We are talking about the purpose of life, and it should be treated as such.

This is the bottom line. A summation of the way, of all authentic ways. Simple. And practical.

And, here’s the koan, the pointer and the invitation:

Sit quietly, open your heart, and pay attention.

The koan: Just sit.

Live harmoniously within this world, modestly, and with care.

The koan: Just this.

And, find your path, one that calls on you to explore the ways of the heart, and which attends to the power of the mind.

The koan: Is it one? Is it two?

Do this, and the sages all tell us, the way will open. Actually, the door has been open since before the creation of the stars.

Walk through that door and find the seat that has long been set for you at the table.