BENDING TOWARD JUSTICE

Theodore Parker’s Religion, and Ours

James Ishmael Ford

A Sermon

5 February 2017

Unitarian Universalist Church

Long Beach, California

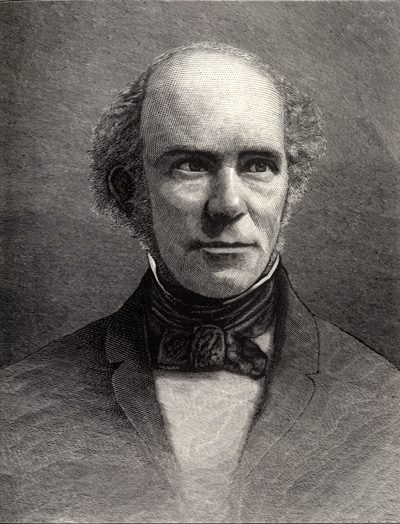

Theodore Parker was born on the family farm in Lexington, Massachusetts, on August the 24th, 1810. His paternal grandfather, John, was in command of the Minutemen on that day thirty-five years earlier. When the Minutemen confronted the British regulars, he declared, “If they mean to have war, let it begin here.” And there it began.

So, Theodore was born to American aristocracy, if you will – although, it wasn’t a family that actually profited out of their place in our history. In fact farming in that rocky New England soil was pretty hardscrabble. Theodore was the ninth child in the family, of which only five survived to adulthood. His mother died when he was eleven, and his father struggled to keep the family going.

Everyone quickly noticed Theodore was brilliant. He quickly moved beyond what was offered at local schools, teaching himself advanced math, Latin, Hebrew, and whatever else caught his interest. At sixteen he began teaching school, and between what he earned and what little the family could raise, at nineteen Theodore went off to Harvard, if only as a day student, which meant not eligible for a degree.

He quickly found himself moving in very interesting circles. Among his friends and mentors were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, and Maria Lydia Child. Pretty much all his friends encouraged him to enter the ministry. Around the same time he met Lydia Dodge Cabot of, yes, those Cabots, of whom it was later said, “the Lowells talk only to Cabots, and the Cabots talk only to God.” They fell in love, and promised themselves to each other. But, he had to have a profession to support his family. And, everyone knew what that profession should be.

Theodore’s parish minister Convers Francis found most of the necessary money, although the Cabot family appears to have helped, as well, to send him to Harvard’s divinity school. In 1837, having graduated he and Lydia married and he was called to his first church, a tiny congregation of some sixty souls. The congregation was, as was he, Unitarian.

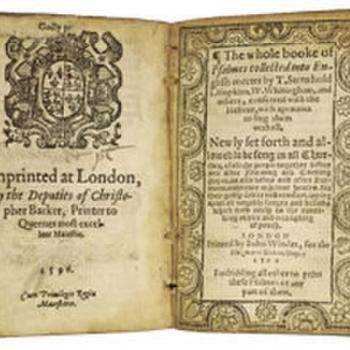

Now, the first wave of Unitarianism that had emerged a generation earlier was highly rationalist, sparking a current that continues a central part of who we are right to this day and this place. However, only a generation from its differentiation out of orthodox Christian congregationalism, there was a sense the emerging tradition wasn’t complete. There was a sense that as valuable as it was, reason wasn’t fully enough.

Seeking a fuller view, a more comprehensive spirituality, American Unitarianism would birth the Transcendentalist movement. Now, Transcendentalism was a literary phenomenon for America writ large, and critical to establishing our American intellectual culture. But at heart it was a burning theological concern among our direct spiritual ancestors. Not unlike, I notice, how the spirituality of Zen Buddhism would also help shape Japanese culture.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was the leading light of that movement. But, Parker, widely read, multi-lingual, and by common ascent usually the smartest person in the room, was quickly seen as Emerson’s equal among the principal Transcendentalists. His place as a signal figure in our movement was secured with one sermon, which he preached in 1841 for the ordination of Charles Shackford at the Hawes Place Church, in Boston. It was titled “A Discourse on the Transient and Permanent in Christianity.” And with it we can say the second wave of Unitarianism was full upon us, a spiritual tidal wave.

Parker preached an “absolute religion,” where “God was immanent in matter and man,” totally accessible to each of us as our natural right directly through what was called both “reason” and now “intuition.” The discovery through this faculty with both those names was itself a turning of the heart, revealing God was in everything. Including, of course, you and me. The consequences of this assertion are many. In the same sermon, following Emerson’s even more famous “Divinity School Address,” as a central theme Parker dismissed biblical miracles, indeed any miraculous authority ascribed to the Bible or Jesus. Instead authority was seated in the human mind, or, for the Transcendentalists, equally good language, the human heart.

Again, I find a fascinating parallel in the Chinese word Xin (in Pinyin, Hsin in the Wade Giles transliteration), a term critical in properly understanding Zen, which means both mind and heart. Asserting mind and heart as one thing opens wide the doors of possibility. Each angle on this amazing human faculty becomes a corrective for the excesses of the other. And together, we find a dynamic engagement with this world.

I cannot overstate the importance of that sermon. Or, the controversy it sparked. On the one hand Parker was denounced by both the orthodox and many of first wave Unitarians, even to the point of being denied pulpit exchanges with colleagues for many years. While on the other hand, his congregation, as I mentioned when he arrived counted sixty souls grew to several thousand, and swelled up to seven thousand when he preached on particularly controversial subjects.

While Parker’s Transcendentalism, like Emerson’s owed much to Platonism, with a constant call to some ideal beyond the body, there were at the same time other Transcendentalist currents, such as Thoreau’s attention to the “thing in itself,” an even more naturalistic view, with which I personally find more affinity. That comprehensiveness, that willingness for a level of ambiguity is also critical to our emerging spirituality. And, something that continues to this day.

But, whether it was Emerson and Parker’s Platonic idealism or Thoreau’s more naturalistic mysticism, Transcendentalism called us to examine our own hearts and the world through that faculty, which in our inheritance can be called either “reason” or “intuition.” I find it really important how for them there was no particular difference between the two, reason from this angle, intuition from that. This is a much richer understanding of how we actually come to know things than many of us tend to notice. Perhaps we can unpack that further at some other time.

Here let’s explore just a little what this meant for Parker. In that sermon sorting the transient from the permanent, he proclaimed, “Christianity is not a system of doctrines, but rather a method of attaining oneness with God. (And a quick pause. Take that word as an invitation to whatever ultimate values you hold, be it higher power, intimate love, or, as I personally prefer, the totality of the world. That oneness with what we find divine) demands, therefore, a good life of piety within, of purity without, and gives the promise that whoso does God’s will, shall know of God’s doctrine.” With this Parker articulated a radical doctrine, declaring we are our true selves when we have nothing between God and us, between the ultimate and me, between the world writ large and you.

If his life stopped there, Theodore Parker would be assured a place in our liberal spiritual pantheon.

But there was also that man who hid runaway slaves in his home and who wrote his sermons with a loaded pistol resting on his desk, knowing his house could at any tie be assaulted by slave catchers. He was a member of the Secret Six, who if you’re unaware of them, were prominent New Englanders who underwrote John Brown’s abortive attempt to arm a slave rebellion. In fact in the wake of the attack on Harper’s Ferry and its failure, several of the six fled to Canada. Parker, as circumstances had it, had developed tuberculosis which had previously claimed many members of his family, and was in Europe, at the time, and where he died. Otherwise, who knows, he could have been arrested and charged with treason, today, perhaps abetting terrorism. I think of that old line about freedom fighter and terrorist and the eye of the beholder, and I very much find myself thinking about our ancestor Theodore Parker.

Parker’s sense was that his direct encounter with the divine also called him into a life of action, to see the divine everywhere, to perceive a divine harmony with one’s self, and then to act in its service. One biographer noted his advocacy for “temperance, education, the condition of women, penal legislation, prison discipline, the moral and mental destitution of the rich, (and) the physical destitution of the poor.” He also called for universal suffrage for both women and African Americans. Now, his views on race were in fact complicated, and evolved throughout his life. No one rises completely out of their time and place. But, oh my, we’re talking about someone living in the first half of the Nineteenth century, advocating for things we mostly assume as natural human rights, but then, were not. Absolutely were not.

My own path is more wary of weapons than Theodore Parker’s, although I don’t and honestly can’t claim to be a pacifist. I think pacifism can be an ethical, moral, and spiritual discipline that one can consciously embrace. And I think the unintended consequences of violence are too many, and too ugly to argue for arms in any but the most extreme circumstances. But those circumstances exist. And the horrors of chattel slavery are a really good example from that time and place. And that pistol on that writing desk made a lot of sense. So, complicated. Our spiritual way calls for moderation in all things, including as the old saw goes, moderation itself. But. And. The conundrums of life lived. Life is complicated.

And Theodore Parker was a complex person. He did not, I gather, play well with others. And this caused a lot of unnecessary hurt. But, he also pushed our association of congregations toward an ever-larger faith, one that would allow in good time, us, who we are today in all our wild glory. When he died in Florence, he was not quite fifty years old. On occasion I wonder, what if? Beyond the possible trial for sedition or treason, what if that fertile mind continued for another decade or two or three?

I find him enormously attractive, and so important. And he certainly challenges us, even today. For instance, in 1853, Theodore Parker had preached another sermon, “Justice and the Conscience.” There he proclaimed, “I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; (but) I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.”

A century and almost a decade later, Dr Martin Luther King, Jr, another admirer of Parker, who often cited the old Transcendentalist in his sermons, called out to us, “I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because truth crushed to earth will rise again. How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever. How long? Not long, because you shall reap what you sow…. How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

And Parker’s influence continues, modified, corrected, expanded. Four decades and three years after Dr King’s words, our former, and as far as I’m concerned at least in my heart still president Barack Obama, speaking on the anniversary of King’s assassination, proclaimed, “Dr. King once said that the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. It bends towards justice, but here is the thing: it does not bend on its own. It bends because each of us in our own ways put our hand on that arc and we bend it in the direction of justice….”

Here I think we find what Theodore Parker called us to: To see the connections, to reflect on those connections, and then to act in the world inspired by those connections, each of us, in our own way.

I think about how we still live with the unfolding consequences of slavery and how we drew short at the moral repair called for in reconstruction. With terrible consequences, so that even today a rite of adolescence for a black adolescent male is for his parents to have what they call “the talk,” about how to survive when going out in public in their, in our nation. Here in this country where slights and prejudice and a vastly greater likelihood of poverty follow being black like night follows day. And, with all of this, I find myself thinking of those young hotheads who put it all on the line in that loose alliance we call Black Lives Matter. And I think of what Reverend Parker would likely have said, and done. And I think about me, and I think about us.

And now a great tragedy has overtaken the Republic. We have someone with no moral compass as our president. We have someone who ran a campaign disparaging all who might be perceived as “others.” His propensity for scapegoating the powerless and now apparently implementing that as policy runs cold in my heart. And, I think about me, and I think about us.

So, what does it mean to be a Unitarian Universalist in this time, and in this place? What does it mean to be a spiritual heir to Theodore Parker?

Well, you know, if you look through the dust flying around it’s pretty straight-forward. We commit to looking at ourselves and the world, as deeply as possible. We commit to seeing the connections. And we commit to putting our hand on that arc. Of course we will make mistakes. I look at the young people who are loudly and sometimes unpleasantly pushing us to look at the sins of our time and place, and calling us to correct this based in their knowledge, their body knowledge of mutuality, of interdependence, of our accountability to each other, and I know they are going in the right direction.

This is the very same direction that informed Theodore Parker, and which informs our spiritual way. If you have the moral compass, if you see our essential connection with each other is nothing less than the divine itself, then with false steps and mistakes along the way, of course with false steps, we will nonetheless go in the right direction. We will bend that arc.

Our way is about paying attention, acting, correcting, reflecting, and acting again. And, here’s some good news: so far as our human lives are concerned, we do this, and on balance, on balance, mysterious, wondrous, joyful things will emerge. Our hands will join together on that arc, and bend it toward justice.

We do this, and not only will our own hearts find healing, but, our world itself, and the arc of history might indeed, be bent in that divine direction.

This was Theodore Parker’s faith. And, dear ones, no doubt, it is ours.

Amen.