To quote from myself, because, well, because I can, in my history of Zen Buddhism come west, “Zen Master Who?” I describe the first of the several times I met Alan Watts. It was sometime, I believe, in 1969.

“I was on the guest staff of the Zen monastery in Oakland led by Roshi Jiyu Kennett. I was enormously excited to actually meet this famous man, the great interpreter of the Zen way. Wearing my very best robes, I waited for him to show up; and waited and waited. Nearly an hour later, Watts arrived dressed in a kimono, accompanied by a fawning young woman and an equally fawning young man. It was hard not to notice his interest in the young woman who, as a monk, I was embarrassed to observe seemed not to be wearing any underwear. I was also awkwardly aware that Watts seemed intoxicated.”

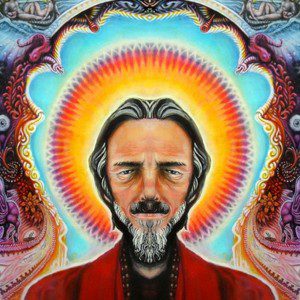

Alan Watts was in fact the first person to write popular books about Zen in the West, beginning in 1937 with the “Spirit of Zen,” and more importantly in 1957 with his best selling “Way of Zen.” He drew mainly on the scholarly volumes just being written by D. T. Suzuki, the first person to write authentically about Zen in European languages, through Watts engaging style made enormously readable and genuinely compelling. As I summarized in my history, “An erstwhile Episcopal priest, engaging raconteur, and scandalous libertine, Alan Watts was also a prolific author whose books created an inviting sense of Zen-as-pure-experience and a do-what-you-want spirituality. These qualities both profoundly misrepresented Zen and led many people to it.”

On that last note, some years later I attended a talk by an American Zen priest. At the end, during the question and answer period, someone asked about Watts. The priest sighed, and then said, “I know there’s a lot of controversy about Alan Watts and what he really understood about Zen.” He paused. And then, added, “But, you know, without Alan Watts, I wouldn’t be standing here on this platform.” I have to say, in large part, that’s true for me as well. In the 1960s and 70s, Alan Watts opened some important doors for many of us looking for a new way.

Over these passing years I’ve come to feel the title of his biography “In My Own Way” and the title of the English edition of Monica Furlong’s biography of him, “Genuine Fake,” taken together points to the complexities of this intriguing Anglo-American Zen trickster/ancestor of our contemporary spiritual scene.

In a relentless critique of Alan Watts, Lou Nordstrom and Richard Pilgrim point out how an authentic spirituality must encompass “practice, discipline, and effort,” features completely lacking in Alan Watts’ “Zen.” In large part I agree, but not completely. There is absolutely a place of falling away of practice, discipline, and effort. As we open our hearts we find the way is in fact broad and forgiving. And it seems he tasted that freedom and joy. I really believe he did. But, the authentic spiritual is also in that delightful conundrum of a real life, totally bound up with practice, discipline, and effort. The way is also, without a doubt, harsh and demands everything. And here Watts seems completely clueless.

Now, in my opinion, Alan Watts was at his very best during a brief period when he tried at practice, discipline, and effort. Or, at least stood in their general neighborhood. Raised in England, his natal tradition was Anglicanism, although he formally abandoned it by sixteen for the eclectic Buddhism of the London Buddhist Society. In his late twenties, having come to America and desperate for an occupation that paid something, he decided to become an Episcopal priest. He had not attended college, but by providing a very long list of the books he had read and then showing a suspicious faculty he had not only read them, but profoundly absorbed them, he was admitted into the divinity program at Seabury-Western Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois.

Watts graduated with a masters degree in divinity and was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1945. He was immediately engaged as the Episcopal chaplain at Northwestern University. He was thirty years old. It appears to have been an amazing moment. He was wildly popular on campus, and his books were received in progressive religious circles as challenging and compelling. And then within five years Watts was out of the ministry, for many reasons not least of which was when his wife sued for an annulment on grounds of adultery. This part would become something of a pattern for his life.

For our time here I want to remain focused within that Christian moment. His divinity degree thesis was reworked and published as the book “Behold the Spirit: A Study in the Necessity of Mystical Religion,” first released in 1947. I can’t tell if it has ever been out of print. What I do know is you can buy a new copy today, there’s even a Kindle version.

It’s really interesting, an attempt at synthesizing eastern and western spirituality grounded in a broad and sympathetic expression of Anglicanism. I’ve seen the term “monistic” or “nondual Christianity” being used here and there lately. Monistic or nondual as in the reconciliation of the myriad things of the world within an interdependence so complete one can speak of it all taken together as one. Of course, variations on monism are at the heart of much of Eastern religions, certainly of Hinduism and Buddhism and Taoism.

While one can argue there have been nondual currents in Christianity, particularly among some although not most early gnostic schools, this perspective has definitely not been a part of normative Christianity. In mainstream Christianity the world and God are seen as relentlessly separate, creator and created. A world of problems have followed this setting up of a hierarchy with the spirit above and good and the world below and condemned.

If the proposition that the world is completely separate from the divine were true, well, we would just have to live with it. But, and let me make a categorical statement rather than my general hedging: That’s not true. Rather, as I open my heart to the world, the world, the great mess that is you and me and all things, I find each thing is created by and creating the host of other things at the same time, in a dance or web of intimacy, where each of us is a moment in a shimmering play of reality. And, that play of reality is exactly where I find the divine, the holy, the sacred. Here. I don’t need to go to some other place to find it.

Me, I see no need of some extra bit. Perhaps why I am not a mainstream Christian, or anywhere near by. That said there are today a host of emergent Christians who don’t see the separation, either. Richard Rohr and Cynthia Bougeault are two contemporary and apparently popular writers that fit the bill. I would add in Bruno Barnhart, Bougeault’s mentor, as well as a variety of Hindu influenced Christians like the nun Sara Grant, the anonymous Cistercian monk who writes under the name “a Monk of the West,” as well as, well the list is increasingly long, but such folk as the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart and the moderns Thomas Keating, Bede Griffiths, and Martha Reeves, who write as “Maggie Ross” are a pretty good start for those who wish to pursue this further.

And, Alan Watts’ book kind of spells it all out in a way perhaps even best done by someone not actually immersed, as he was, standing more in the neighborhood of that “practice, discipline, and effort” than within it. Of course that distance also means he misses some things. Additionally I find Watts a tad too comfortable with his own insight, unchecked by others who’ve walked the way before, a danger for the spiritually unaffiliated. All this acknowledged there remains something quite wonderful…

Behold the Spirit was a revelation when published nearly seventy years ago. It was, I gather, and perhaps obviously, criticized for its “creeping pantheism.” The book was in fact a through going panenthiest screed, probably the most compatible Christian variation on pantheism, the other word for nondual or monistic spirituality, where in panentheism the world is seen is divine, but that the divine, God, cannot be limited to the universe. Even with that accepting at some point an other of some sort, this panentheism is still a major step from the normative vision of the Christian church.

And with all this taken together a question bubbles up, and which, in a meditation he wrote a quarter of a century later, Watts’ asks on behalf of all those who would challenge his thesis. “Can Christianity abandon the monarchical image of God (a God separate from all that is in a great split between creator and created) and still be Christianity?” To which he responds with another question, a rather burning one, as I feel it in my heart, “(W)hich is more important – to be Christian or to be at one with God?” Or, for me: to follow some orthodoxy of separation, and cut myself off from what is calling to every molecule of my being, or commit whole-heartedly to the great play of the many as one found as I open myself to the world as it presents?

A worthy challenge, I believe, perhaps the great challenge. And, I think Watts in fact spells out a fair amount of what an affirmation of a nondual Christianity can look like in his thesis and book. The sad thing, as I see it, was that he couldn’t follow through for himself. His personality, what he liked to characterize as his “bohemian personality” just didn’t have a fit in the organized church. I’d have to add his lack of personal boundaries would have meant he would never had made it as a Unitarian Universalist minister, either. He was born to be an outsider. And after that five years stirring up the Anglican church he made sure he would forever be an outsider.

But he also pointed a way.

First he spells out a reality that I find resonates with my experience. The metaphors are straight out of the traditional church, which I think can be helpful for Westerners hoping to find the real. More complicated for me is a relentless masculine by preference language. But, if we allow ourselves to listen, we find the underlying understanding he presents shakes the very foundations of the moral universe the conventional church preaches. He declares:

“God is the most obvious thing in the world. He is absolutely self-evident – the simplest, clearest and closest reality of life and consiousness. We are only unaware of him because we are too complicated, for our vision is darkened by the complexity of pride.

“We seek him beyond the horizon with our noses lifted high in the air, and fail to see that he lies at our vary feet. We flatter ourselves in premeditating the long, long journey we are going to take in order to find him, the giddy heights of spiritual progress we are going to scale, and all the time are unaware of the truth that ‘God is nearer to us than we are to ourselves.’ We are like birds flying in quest of the air, or men with lighted candles searching through the darkness for fire.”

Then he lays out the traditions of the Christian church as a manifestation of this truth of our radical interdependence, of our bottomless unity. The man who can only stand in the neighborhood of practice, discipline, and effort, shows where it can be found. I think in part because he really did taste the deeper truths, really did to some degree, and none of us are judge of how deep any other, or for that matter, even we ourselves have traveled, really did touch the great insight.

So, as the Episcopal priest, Martin Smith noted, Even “as a mirror reflects all colors and shapes without interference,” Alan Watts could call us to stand in the place of the wise heart. “(I)n the same way the mystical awareness of God does not contest place with other experiences and state(s) of mind. Mental states such as joy, sorrow, exaltation, dejection, pleasure, and pain are as a rule mutually exclusive. But the mystical stage is inclusive, just as God and His love include the whole universe. There is no conflict between experiencing the Now and things which happen in the Now.”

Smith touches the heart of wisdom as Alan Watts presented it. This is an extremely good pointing that even those of us with no affinity for the traditional language of the Christian church, can, none the less, recognize as an expression of what we all find as we open our hearts as wide as the human heart can be opened.

The field is found. And the dance of things within it is revealed.

In his little book and during those five years, Alan Watts showed those who love the Christian tradition how they can turn toward the real without abandoning their tradition.

Genuine fake. A teacher for those willing to follow the way he pointed, but could not himself go.

A wonder. And a joy.

And.

A hint of possibilities for us all.