A Meditation on Unitarian Universalism, Rational Religion & the Great Humanist Way

James Ishmael Ford

19 February 2012

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

The way that can be described

is not the way

The name that can be spoken

is not the name

The unnamable is the mystery

Naming is the mother

of all things

Free from grasping, you see it

Tangled in concepts, you see only yourself

And yet, the mystery & the projections

Have the same source.

Darkness.

Darkness within darkness

The gateway to wisdom.

Tao Te Ching

Last Thursday evening Jan and a host of us from church drove over to Cranston to join the throng hoping to influence the School Committee’s decision whether to appeal the lower court ruling that the prayer banner on display at Cranston High School West be removed. As an admirer of young Jessica Alquist’s principled and constitutionally informed stand on behalf of minority views, I was glad for how it all turned out, if not quite so sanguine about what many people said or did during the hearing.

I was distressed at how both atheism and humanism were blamed for pretty much all the ills we experience today. Of course, the way the human brain sometimes works, it reminded me of a joke.

I’m sure you’ve heard it in one variation or another. The set up is simple as pie. A man is caught in a terrible automobile accident. It takes the jaws of life to extract him from the mangle. He’s on the stretcher, the EMTs look him over and one says to the other, “It doesn’t look good. Should I call a priest?” The other EMT notices a button with a flaming chalice on his jacket, and says, “No. He’s a Unitarian Universalist. Call a math teacher.”

Now, I think the spirit, the worthy point that hides within this joke is also expressed within something Henry David Thoreau once said. When asked his opinion about the afterlife, Henry replied, “One world at a time.” Call a math teacher. One world at a time. When people think of Unitarian Universalists they often think humanism. In light of the harsh things said about humanism at that meeting, perhaps it would be good to pause and think about it.

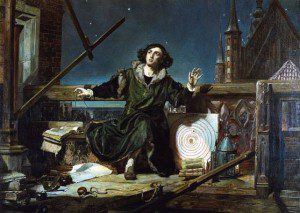

Today I want to talk about humanism, what it means, and what it has to do with us as a community of faith. And today seems particularly appropriate to do so. Not only is it in the wake of our local turmoil around civil liberties and blaming atheists and humanists for upsetting the cart, for all sorts of bad things, but as it happens, Nicolaus Copernicus happened to be born on this day in 1473. Quite literally a Renaissance man, he was a jurist, a mathematician and an astronomer. And frankly, when I think humanist, I think of someone rather like him.

Copernicus was also ordained within the Roman Catholic church, his exact rank isn’t completely clear, but almost certainly a priest; he was, after all, once nominated to be a bishop. He also caused the church a great deal of unease and for some who followed his work considerable discomfort as his relentless pursuit of truth led him to prove the previously universally accepted opinion the earth stood at the center of things was not so; replacing the earth with the sun, and then going one step further, establishing even our sun which we’re twirling about is not the center of things.

Now, it is probably worth noting he chose to wait until his deathbed to publish, and the consequences of his work would, as I said, fall on other shoulders. Think Giordano Bruno and Galileo Galilei. Humanism lived does upset carts. But, for our brief time together, what I really want to hold up is the possibility of finding the sacred within the natural realm. Which, best I can tell, is something that marked Copernicus’s life and work. And, which, I suggest, is what humanism is all about.

Back to that joke. Back to one world at a time. I hope you’ll allow me a strong statement about who we are. Yes, we have absolute freedom of conscience, and no one is forced to assent to any statement made anywhere by any one of us, including from this pulpit and by me. But, here’s a truth: any serious observer can see something as common among us, so common as to be descriptive. We are within our tradition, for the most part, humanists. And we have been since our foundations. Humanists.

This humanism works for atheists, agnostics and theists of many different flavors. At the School Committee meeting I understand Greg Epstein the Harvard humanist chaplain was there. I didn’t get to meet him, but I am quite interested in his work. I believe what he is offering at Harvard maps closely what we do, he just markets it to atheists and the closely aligned. We, at our best, are far less discriminating. And I think there are good reasons for our humanism to be so wildly, extravagantly, promiscuously so. But I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

In fact in recent decades there’s been a bit of confusion about our basic humanist stance within our community. I think this is so for a number of reasons. For one, because to many humanism has come to be associated with a hard and uncompromising atheism. Think of the New Atheists who take no prisoners and are relentlessly judgmental about anyone who uses religious language.

This in fact was a stance taken during much of the twentieth century by many our own identified humanists. Today, for many of us, a large majority I would say, such a bare, aggressive and frequently bitterly angry atheism, understandable as it might be considering how atheists are so frequently and unjustly treated, just isn’t what we’re about. Even, I hasten to add, as we cherish atheism and agnosticism as viable stances within our association. Particularly agnosticism, but again, I’m inclined to rush ahead of myself.

Another reason, I suggest, for the confusion arises out of our association with Hungarian speaking Unitarians. They’re a compelling faith community, touching many of our hearts as people who have suffered terribly for their faith in one God, and for that reason people also called Unitarian. We have a sense of but for the luck of the draw, there goes we. And, on balance I think our association has been good for both communities.

But, because of that shared name, which has brought us together, and because they’re a Reformation church, and therefore from the early-mid sixteenth century while English speaking Unitarianism is an Enlightenment phenomenon, and therefore dating from the mid-late seventeenth century, many of us assume that the one led to the other. Many people, thinking we come from them, have come to think their spiritual concerns are ours. This is, however, not so. It arises from a common enough error, a logical fallacy, known as Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, or Post Hoc for short.

Reformation Unitarianism, which arose and flourishes in Hungarian speaking countries was about the nature of God pretty much completely within a Christian context. These continue to be their concerns. But, they are not ours.

Enlightenment Unitarianism, which arose and flourishes in English speaking countries was about how we approach reality, most distinctively approaching religion with a critical eye. The term Unitarian itself, that “one God” part of our position was almost incidental for us. We did reject trinity as there was no conclusive evidence for it within the scriptures. It was not logical for a central doctrine to lack unambiguous support in the primary text.

The name was given us by those who didn’t like us and thought it the most insulting thing they could do. Until the blessed William Ellery Channing accepted the name on our behalf, and it is a nice name, we tended to call ourselves liberals and our faith stance was called rational religion. Throughout our real concern was how to live a holy life, a life of meaning and purpose in the world in which we found ourselves. And following that light, steadily over the years, we shifted from being a liberal Christian church, to becoming a liberal Church with Christians. Actually we’re a liberal church with Christians, Jews, Buddhists, pagans, atheists and theists and agnostics, along with many, many miscellaneous others.

The liberal thread that has joined the many different faces of English speaking Unitarianism, is called religious humanism, or rational religion, humanism for short. Of course humanism is another term that has different senses within different communities, so, let me give a brief definition for what we tend to mean. We do not mean humans are the center of things. By humanism we here tend to mean, whatever else might be true, our focus, our concern, our delight is found in this world as we actually encounter it.

Humanism is a path of humility. It follows the great dictum of not knowing, of not settling, of endless curiosity. Humanism is finding our way within a natural world, in which our natural ability to reason and its great flowering as scientific method are seen as things to be cherished and fostered. And we don’t stop there. Humanism is also about music and art and dance, it is all about embodiment.

That said the club is big. Atheist? Great. Christian? Wonderful. We’re all welcome. This is why we’ve been able to welcome pagans and Buddhists in significant numbers into our community over the past decades. The deal is we have a covenant of presence, to each other, and to this precious, hurting, world. Look at us in this spiritual community, as we actually are, shortcomings and accomplishments all taken together, and you can see what that means.

In this lovely old Meeting House today we count that wild kaleidoscopic range of views as natural. What runs a current, a great rushing tide through our hearts and makes us as one, within all our many spiritualties, is that profound this-worldliness. Just this. Just this. Examined and loved and lived. Lived. That’s why social justice is so important to us. It follows our humanist spirituality, our looking at who we are, really are, and that finding of how we are one family. Knowing this how can we help but act to be of some use in the healing of hurt?

Of course this approach to life can have its shadows, and does. Within our history we see how we can be hyper rational and miss the music of our lives. I’ve already noted how this narrowness marked many of us through much of the twentieth century. And sometimes we over react to our rationalism and can get pretty mushy. So, for instance, we provided a fair amount of the leadership for the spiritualist movement in the late nineteenth century. Not our most rational moment. But, also, whether some large part of us tilts one way or the other, somehow we always seem to correct. And moving a bit one way or another, over time the current that holds for us is a dynamic and spiritual humanism.

Over the past near three hundred years, of all the Western religions we seem the one most clearly identified with the rational and the naturalistic. Not the only ones. We owe an enormous debt to the rationalist and humanist current in Judaism. And there are similar rational currents within Christianity, lifted one could argue from classical Greek philosophy, but there, nonetheless. I think it a delightful sign of this that the American Episcopal church celebrates a feast for Copernicus. The telling difference is their feast is on the anniversary of his death, while our marking today is for his birth.

So, what might this all look like for us today? How shall we go forward?

A while back the comic book writer Alan Moore, creator of the Watchmen and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen as well as V is for Vendetta was interviewed for the New Humanist. Perhaps ironically, maybe simply fortuitously, he summarized what I think is our work today as spiritual humanists.

“My basic premise” said Moore. “Is that human beings are amphibious, in the etymological sense of ‘two lives’. We have one life in the solid material world that is most perfectly measured by science. Science is the most exquisite tool that we’ve developed for measuring that hard, physical, material world. Then there is the world of ideas, which is inside our head. I would say that both of these worlds are equally real – they’re just real in different ways.”

I believe our work today, as a community, is to bring the worlds of science and poetry and myth together, to join head and heart, to find the spirituality, the spirit, the breath of hope within our ordinary lives. We are called to live in this world and to dream dreams of possibility. The work we can do out of that knowing, well, really it is a not knowing, it is that endless curiosity, which arises in the human heart opened, is nothing less than sacred.

And, let me tell you a secret. The world needs this. It needs us.

Amen.