Last week, Pakistani education activist Malala Yousafzai was declared a co-winner of the coveted Nobel Peace Prize, along with activist Kailash Satyarthi. Since then there have been numerous articles, support pieces and critiques addressing her win, and the expected conspiracy theories. The announcement even reheated a discussion on the validity and relevance of the Nobel Peace Prize itself.

We have covered Malala a few times on MMW. Merium has written of the media frenzies that have engulfed Malala. And Nicole Mostafa wrote about cynicism surrounding Malala outside of Pakistan.

I haven’t read Malala’s best-selling book I Am Malala, but I intend to read it when my daughter finishes it. Her memoir (I think that term is funny when it is co-written by a 15 year-old) is recommended reading for middle schoolers by teachers and school boards around the world. From what I’ve read in a Toronto Star review, the book, which is based onMalala’s life events, it is an incredible story of bravery: willingness to persevere coupled with a great thirst for knowledge while advocating for equal educational opportunities in a hostile environment.

The girl is a champion, no doubt. She is a survivor.

But I was simultaneously taken and mortified by an interview she did one year ago with Anna Maria Tremonti of the CBC. She spoke so plainly about her brutal attack by the Taliban (she was shot in the face at close range in 2012), something that was undoubtedly traumatic. I was upset that a woman (still recovering from her injuries) was having to rehash, over and over, the violence that she experienced. I was impressed at how candidly she spoke of her intentions to advocate for education for girls and challenge the community.

I find myself increasingly irritated with people who assume that I am an unpatriotic Pakistani for criticizing the system around Malala. The young woman is admirable. But the context is important. This means I will not be purchasing a Malala t-shirt or buying a book of poetry dedicated to Malala anytime soon.

My problem is not this intrepid young woman. I am doubtful and suspicious of disingenuous agencies that want to exploit Malala for their own agendas and refuse to recognize their own roles in creating those terrorists they claim to detest.

I am skeptical of her being lauded by governments who continue to bomb and drone her neighbours and her country.

I also think it is easy for writers to point out ridiculous Pakistani critiques (and yes, there are many) and focus on the claim that a majority of Pakistan dislikes or rejects her. This fuels a narrative that Pakistanis are heartless and ignorant. So much that Zaid Jilani, an American-Pakistani journalist wrote a piece aptly titled… wait for it… “Actually, All Pakistanis Don’t Hate Malala.”

There appear to be two choices with regards to what I call #Malalagate:

1) You can support her and boast on social media, or

2) You can critique an aspect related to Malala’s win and be berated and accused of being a conspiracy theorist.

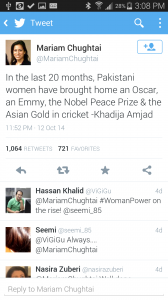

My concerns are not so shallow that I am not interested in seeing a young woman succeed. Pakistani woman have been struggling and succeeding for centuries – whether or not they are lauded by the West.

But after I posted a very well-formulated article about this topic on Facebook, the comments section went off. I was messaged privately by a friend (Pakistani living in the US) who was very offended that I shared such a piece. “Where is your loyalty?” he asked me. “What kind of proud Pakistani are you?” He went on to insist that because I am in Canada, that my legitimacy was compromised.

Suffice it to say, we are no longer connected on Facebook. Unfortunately, patience is not my strong suit and I didn’t feel the need to explain or defend my allegiance to Pakistan. The conversation was angry and soon over.

I was vexed but calmed my nerves making chicken pulao and haleem cursing him in every profanity I knew in Urdu and Pashtu. *sidenote: I have accumulated a great many*

For the record, critical analyses of this issue don’t render me less patriotic. According to my father, not liking mangoes is a far worse offense for a Pakistani.

The piece that most resonated with me was offered by Middle East Revisited’s blog.

“And while the West applauds Malala (as they should), I am afraid it might be for the wrong reasons, or with a wrong perspective. It feels like the West wants to gain an agenda that suits them or the policies they want. That is also why Malala’s views on Islam are rarely presented. She uses her faith as a framework to argue for the importance of education rather than making Islam a justification for oppression, but that is rarely mentioned. It also ‘doesn’t fit.’”

Malala’s voice is strong but her thoughts are filtered by media coverage and not all of her points are brought forward. When she met with Barack Obama last year, she was clear on her opinion of drones and how they “fuel terrorism.” That statement was omitted from most mainstream media reports.

But her image, which is indeed one of bravery and resilience is used and, dare I say, packaged to the convenience of the West.

Writer and Activist Arundhati Roy recently expressed similar thoughts in an interview with Laura Flanders.

“It’s a difficult thing to talk about because Malala is a brave girl. And I think she has even now started speaking out against the US invasions and bombings that are going on, but certainly… as an individual it is very difficult to resist these great powers trying to co-opt you and trying to use you in certain ways. And she’s only a kid and she cannot be faulted at all for what she did.”

The idea that Malala’s image may be appropriated by disingenuous people with political agendas is not a novel concept.

Malala was scheduled to be awarded honorary Canadian citizenship this week (although the ceremony was cancelled yesterday in the wake of shootings in Ottawa), as only the sixth person to ever receive such an honour. Ironically, this award is being conferred by a government that is not exactly sympathetic to the needs of Muslim women. The Prime Minister has stated that “Islamic terrorism” is “the biggest threat to Canada.” (The biggest threat couldn’t possibly be a crisis of missing aboriginal women or pathetic environmental stances.) But Harper will prop up Malala to diffuse critics and insist that he is an ally of Muslims.

That is a clear example of why Malala herself is not the problem; those who use her branded image are.

It can be rather exhausting to have to keep reiterating that while I support Malala, I can’t overlook of other young, brave survivors from Pakistan who do not get any attention or support for surviving attacks. While Malala campaigns for the right to education, governments and organizations deflect their responsibility and accountability by honouring her without engaging with the full extent of what she is saying.

Offering citizenships and visits to the White House is not enough, not for a girl who deserves much more, or for her people.