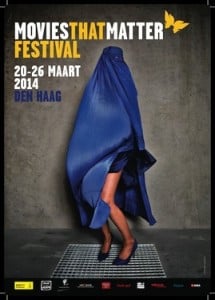

Walking home recently, I rounded the corner from my apartment and noticed a poster that was banal and startling at the same time. I had previously written about the (mis)use of images of Muslim-looking women by Dutch non-profit organisations as an attention-grabbing device, which may or may not be related to the actual work being promoted. Here was another prime example: a film festival poster showing a pair of female legs and high heels peeking out under a blue burqa, blown about above a vent à la Marilyn Monroe in the film Seven Year Itch.

Movies that Matter is a Dutch non-profit organisation that holds an annual film festival, showcasing films dealing with various human rights issues all over the world. It aims to “fuel the dialogue on human rights, influence public opinion and activate the promotion of human rights”. I couldn’t find the objectives of promoting Orientalism and fetishisation of Muslim women’s bodies anywhere in the organisation’s materials, unfortunately.

There is no explanation for the choice of image, so I can only speculate. Burqa-wearing women don’t wear anything else underneath? Muslim women like to wear heels? The burqa as a sign of women’s oppression and therefore a human rights issue? (Yawn.)

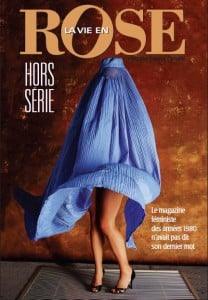

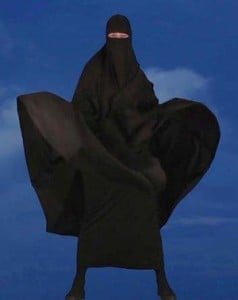

A friend on Facebook directed me to a similar image, photographed almost a decade ago. Turns out that the juxtaposition of an icon of Muslim oppression (burqa) with an American icon of sensual femininity (Marilyn Monroe) might not be such a brilliantly original idea after all.

In 2005, La Vie en Rose, a feminist magazine from Quebec released a special 25th anniversary edition with the following cover, photographed by Suzanne Langevin.

Inside, the magazine asks readers what they might see in this image:

“A woman from Kabul playing Marilyn in front of her mirror? A rival of Marilyn who tries to imagine the choking of the narrow hood, her vision obscured by the netting? Here two icons are juxtaposed against each other: Western femininity, the oppression of fundamentalism, visible restrictions for one, subtle ones for the other. And beneath the stereotypes, a real women of flesh and blood.”

While I appreciate the last line, the description also reveals false dichotomies in this photograph’s creative direction. Both the burqa and the high heels are seen as oppressive features of femininity, with one ostensibly belonging to “the West” and the other from “(religious/Islamic) fundamentalism”.

The same friend who directed me to the image added that she saw the image as implying that Western women face subtle forms of oppression such as “being pressured to reveal more, wear high heels and sexy clothes, but at the same time not being a ‘slut’”. I would say that for my own social circles growing up, there was certainly a pressure to cover up, speak less, and not display any sexuality.

I agree that in all societies, women are pushed towards certain standards of behaviour. Within these norms, women still exercise their agency by navigating their own choices – which can seem either “oppressive” or “freeing” to the outsider.

But what makes covering up or revealing skin oppressive in the first place? Isn’t one woman’s oppression another woman’s freedom? Anthropologist Hanna Papanek has described the burqa as “portable seclusion”, while Lila Abu-Lughod has conceived of it as “mobile homes” – a way to extend the private sphere. Meanwhile, I can safely say that many women enjoy wearing heels or wearing short skirts. The important issue here is having the choice to dress as you wish.

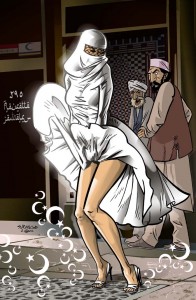

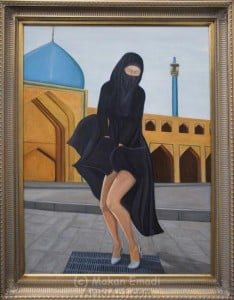

Still intrigued by the likeness of these two images, I did a quick image search on Google for “burqa” and “Marilyn Monroe”. The search revealed that the juxtaposition of the dichotomies of East and West, covering and nudity, freedom and oppression (and perhaps also Muslim Woman and Marilyn Monroe) is also present in popular artistic consciousness.

Unfortunately, the ease with which the niqab or burqa is paired with nudity makes these images not so witty or clever anymore. Rooted in deep-seated Orientalist ideas about the covered-but-secretly-titillating-Muslim-woman, they use sensationalism and stereotypes to capture the viewer’s imagination, but without stimulating any critical commentary on ideas of femininity or agency.