The recent Foreign Policy issue focused on sex drew a number of responses around the internet. Earlier today, we posted a round-up of some of the other blog posts and articles that were written about the issue; here, Sharrae, Azra, Tasnim, Nicole and I discuss our many thoughts on the issue as a whole and on Mona Eltahawy’s article.

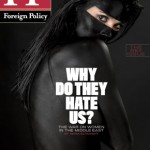

Sharrae: The introduction to Foreign Policy’s online version of their latest issue points out that the U.S. magazines that usually devote a special issue to sex are more often ones like Cosmopolitan – not a surprise. But I want to know, where did they get off devoting a major section of their issue to the portrayal of Muslim women? Was it a means of being controversial? Pushing the boundaries on the discussion on the consent of Muslim women? And by consent, of course, they mean a woman’s consent to dress! Mona Eltahawy’s article “Why Do They Hate Us?” focused specifically on the violence and oppression that women in the Middle East go through. In the same issue of the magazine, Iran-American Karim Sadjadpour also wrote an article on the fixation with sex by Aytollah Kohmeini, and Melanne Verveer discusses why women are a foreign policy issue, and thus celebrates U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for being an advocate for the advancement of women in the Middle East.

Krista: It took me several tries to get past the image attached to the article (as I mentioned in an earlier post, I think Naheed Mustafa captured the problems with the image pretty well), before I was even able to read what Mona Eltahawy was saying. I was actually expecting worse, considering some of the responses I’d seen, so I appreciated seeing moments where Eltahawy acknowledged things like “women continue to be objectified in many “Western” countries (I live in one of them)” and “Clinton represents an administration that openly supports many of those misogynistic despots.” And, well, the stuff she talks about is happening, and gender inequalities really are a problem, and shouldn’t be brushed aside. (Yup, there’s still a “but” coming here.)

Azra: I finally had a chance to read the actual article, but think I’ve become so accustomed to Eltahawy’s schtick that it failed to register and strike a nerve with me this time around. I found it snappy to read and felt some of it to be effectively informative (like when she talks about state-sanctioned policies against women), but I strongly agree with many of the criticisms against it. Is it really any different than her past writing at the end of the day? People who love her past work love this, and people who have been critical of her past writing are critical of this.

Nicole: Mona Eltahawy does have a shtick: her self-appointed job is to be a provocative troll and she goes on various news and media outlets being a troll because, let’s face it, the mainstream media like provocative trollish people. That is why I initially didn’t see anything beyond her classic “I think I’m speaking truth to power but really I’m just giving the MSM what they want to hear” stuff with the “Why do They Hate Us?” article. Then suddenly, my facebook and twitter feeds were full of people completely up in arms. Why were people so hateful and angry this time?

Sharrae: What I think is interesting is that all the writers of the “sex issue” agree that women’s bodies are the world’s battleground. And to be honest, I don’t disagree with that statement either. However, what I find remarkable is that the writers fail to realize the ways that they, themselves, end up waging war on the Muslim woman body. As they (particularly Sadjadpour) condemn Middle Eastern men for making women the symbol of purity in society, they are making Muslim women the symbols of oppression – and liberation. A woman who wears less equals liberation; a sign of a closed gap between men and women, and thus a higher GDP, as those supposedly cloaked under “suffocating cloth” are the symbols of the deep-seeded patriarchy of both Islam and those evil Muslim men. Authors such as Eltahawy or Sadjadpour seem to be caught between two sides. They want to speak to the various problems in their ancestral homeland, but they manage to feed and reproduce images of imperialist notions of those living in the Middle East. “Name me an Arab country, and I’ll recite a litany of abuses fueled by a toxic mix of culture and religion that few seem willing or able to disentangle lest they blaspheme or offend,” Eltahawy commands, after requesting that readers put aside what the United States does or doesn’t do to women.

Krista: Like many others, I was really turned off by the framing of the piece. I’m not sure that “hatred” is really the issue; patriarchy and sexist violence in all societies are rooted in more than just men who hate women. Moreover, “Why do they hate us?” was a rallying cry post-September 11, used to point to “them” as irrational and hateful, and “us” as the good ones. While the “us” is different in Eltahawy’s piece, the “they” is largely the same: violent, irrational, hateful Muslim and/or Arab men. So it’s not just that the title is inaccurate or melodramatic; it’s also very clearly part of the same rhetoric that has drummed up support for wars in the not-so-distant past.

Sharrae: On one hand, I completely understand the need for the truth to be told of how oppression is occurring in various places, yet on the other, I think we should be careful of falling into the pit of perpetuating hate against our (or other) communities. What I think Eltahawy and Sadjadpour fail to do, is provide a deeper context to why these issues exist. In my previous article, I spoke about the arguments of Dina Siddiqi, and the importance of straying away from explanations that tend to simplify politics in the Middle East as simply sensational, and tied up in religious fervour. It is pertinent to assess different contexts depending on the country and society that one discusses. The conflation of Muslim women in Saudi Arabia or Egypt or any other Muslim/Arab country is irresponsible, and glosses over the difference in experience that some women face in these countries. No discussion on class analysis is taken to describe how women from lower classes are more likely to experience patriarchal violence more so than the elite princesses of Saudi Arabia are pronounced.

Nicole: I saw a clip on CNN yesterday, where Mona Eltahawy went on record challenging two of the main criticisms directed at her. First, she denied that she speaks for Arab/Muslim/Brown women; secondly, she asserted that the revolution will not be won by women like her and that she is only a mouthpiece. I find it very savvy of her to take these points head on for once in her career. But as is usual for her, any reasoned dissent or disagreement gets dismissed or brushed off. So I still found it weak sauce when, after the fact, she said that she doesn’t speak for anyone, Arab women speak for themselves, and she then proceeded to name drop all the people she “doesn’t” speak for. She says that all she does it “amplify” the voices of women in the region. What she forgets is that she is where she is – a mainstream media darling – specifically because she DOES speak for people. And let’s face it: sometimes Mona is the only one on TV talking for an on behalf of Arab/Muslim/Brown people. All my respect for that. But instead of using her power as a mouthpiece to write thoughtful, reasoned pieces that reflect the true feelings of women in the region (not speaking for them here, this is as evidenced by the number of counter pieces) or those of Muslim women (of which I am one), she took her voice too far in “Why do they hate us?” Why? Because the article was remarkably simplistic and Orientalist in tone- it is something straight out of Bernard Lewis. That’s not fair to us, but it is exactly what the mainstream media ordered. This is why the revolution won’t be won by people like her, not because she only “amplifies their voices.”

Azra: At the end of the day, Foreign Policy’s reputation takes a huge hit. Foreign Policy’s editorial staff has a massive fail on the title of this piece, the title of an infographic linked to Mona’s piece (“Worst place to be a woman” that highlights the entire continent of Africa), Oriental fantasy photographs of black paint/oil-drenched naked women. It’s sensationalist rhetoric at its best that perpetuates stereotypic representations of Muslim women. It does little to contribute to constructive discussion of the horrendous, intricate social concerns that affect women on the ground in Middle Eastern countries and, really, everywhere. There is little emphasis on empowering women, or the empowered women who are on the ground working for change. Instead we get Mona speaking for everyone.

Tasnim: If Arab society is unmitigatingly misogynistic and in denial about its misogyny, any responses that take issue with the argument can only prove its point.

But this article has provoked more than disagreement; it has provoked a discussion, including many thoughtful responses. I was impressed by Leila Ahmed’s articulate words and Dima Khatib’s measured tone, while my initial frustration found relief in the sarcasm of the colonial feminist’s rebuttal. These responses prompted supporters to make the point that the article has suceeded in its goal: highlighting the issue. Yes, they’ll say, it may have been sensationalist and simplistic, but it worked. You don’t have to work hard to hear “the end justifies the means.”

Nicole: As the American Paki blog says (my favourite of the “rebuttal pieces”), nobody expects Ms. Eltahawy to respond to every single criticism thrown at her. But she seems to only feed on fangirls and fanboys or trolls who slander her. I have yet to see Mona Eltahawy respond to any reasoned argument against what she writes with anything more than sidestepping (as she did when she was asked on Twitter her feelings on the pictures of “Why do they Hate Us”) or vitriol (the despicable way she tweeted at Hebah Ahmed). This bothers me. I can’t deny that Eltahawy has an important role in media discourse but far too often she uses her power, as what could be called a “native informer” as Ibn Kafka says, for herself rather than for the common good. The MSM oversimplify issues affecting Islam and Muslims, and Eltahawy has given them yet again what they want- a simplistic, hateful piece with so-called insight into the minds of her Arab brothers- with “Why do they hate us.” Finally, as Mona Kareem says, Eltahawy has been given “many chances” to speak. Why are her unique and definitely not consensus opinions consistently given priority as gospel?

Krista: I absolutely think it’s worth talking about some of the issues that Eltahawy brings up in her piece, and I agree with Tasnim that the piece has provoked some important discussions. But I think it’s a lot more effective if we lose the language that links us to warmongers, and look more broadly at the roots of violence against women, rather than focusing on “hatred.”

Tasnim: Women’s rights in the Arab world is not an obscure or undiscussed issue. What came through in the responses, for the most part, was a rejection not of the facts but of the presentation, in particular the pathetically predictable images accompanying the article, which were not the writer’s decision.

At one point in Dima Khatib’s response (which I translated here) she asked: “In our Arab society, does the son hate his mother? The brother his sister? The father his daughter?” To borrow Virginia Woolf’s words, instead of asking what can be done to combat the way societies “sink the private brother, whom many of us have reason to respect, and inflate in his stead a monstrous male,” Eltahawy presents a one-dimensional, sterotypical picture of the monstrous male, the “they” who hate “us. “