When the pandemic had just begun, in those frightening March days when everything was shutting down and the virus seemed to be everywhere (yes, I know it’s still everywhere, but we have a much better idea now of where the wheres are and how it gets from one where to another), I noted that the world had suddenly been put on Sabbath.

Sabbath is necessary, and this one was overdue. But the thing about sabbaths is that they end. They are a time for rest and renewal that we avoid at our peril, but from the time that sabbath was established among humans until now, it has been established as part of a rhythm of rest and work. We go into sabbaths for a short time – whether a day, a month, a semester (why did you think sabbaticals were called “sabbat”icals?) or even the ancient Hebrew year of jubilee – and then we emerge on the other side, ready to begin our work anew.

This is no longer a sabbath.

When we emerge – and we will – there will be many things which have permanently changed. Work will be different. School will be different. Church will be different. (I have a whole other post in the works about that.) The supply chain will be different. I may always keep doing yoga in my study on Zoom. Our rhythm is not just renewed; it is permanently altered.

One of the things I discovered during our time of sheltering in place was the Brother Cadfael series of mysteries by Ellis Peters (real name Edith Pargeter). I had heard of the books and TV shows but never read or seen them (autism thing: I take on new fandoms slowly. I take on new everythings slowly). When I fell, I fell hard: I read all 21 books in two weeks. I can see medieval Shrewsbury in my head. I will never be able to stop seeing it.

Most of the rest of you probably already know this, but Cadfael represents one of two ways that people entered religious houses in the Middle Ages. You could go in as an oblatus, a child dedicated to God by your parents who would grow up in a monastery or convent and never know any other life; or you could go as a conversus, a person who previously had a life in the world and chose, for whatever reason, to leave it. Cadfael is a conversus. (In fact, during the series of books the Abbey of Shrewsbury makes that decision that they will no longer take oblate children, but only conversi, people old enough to know what they are choosing.)

Before Cadfael was a monk, he was a Crusader and served as sailor and soldier, and his experiences doing these things are often relevant to the books’ plots. (One of my favorite tales of Cadfael is one of only three short stories that Pargeter wrote about him, “A Light on the Road to Woodstock,” which tells how he came to leave his first life for his second.)

His experience outside the monastery means that he knows what a life unconstrained by the rules and disciplines of the monastic life is like, and he often feels tempted to bend or to leave those constraints – but he doesn’t. (Well, in one book, Brother Cadfael’s Penance, he does, at least for a time. It’s a beautiful book. Read it. But read all the others first.) And honestly, if you’re a detective, being a cloistered medieval monk is kind of a drag. You are just about to follow up on a marvelous clue when – bang – it’s time for Vespers, and to the Abbey choir stalls you must go. And Cadfael does. In fact, even when he’s estranged from the monastery in Brother Cadfael’s Penance, he still says the daily office by himself.

Even before I read Cadfael, I knew from other works (like one of my all-time favorite books, The Cloister Walk by Kathleen Norris) that people who have entered monasteries and convents today often feel such temptations. And yet they go on anyway. Not naively, and not always with a lot of the initial romantic passion; they put one foot in front of the other after the first excitement of their new life fades. They return to the disciplines and restrictions laid on them. They know they are in it for the long haul.

Of course, there is the huge question (and it is a large and serious question) about the unfair effects of our current crisis that send many black and brown and poor and immigrant bodies to the front lines as essential workers even as rich white women like me can stay home and do my job and do yoga and go to church on Zoom. They are the oblati in our coronavirus moment. They didn’t choose this monastery, and they would have every right to leave it.

But for those of us who are conversi, I think Cadfael has a lesson for us. We’re going to be here a while. We are in it for the long haul. Wear your mask, wash your hands, and put one foot in front of the other.

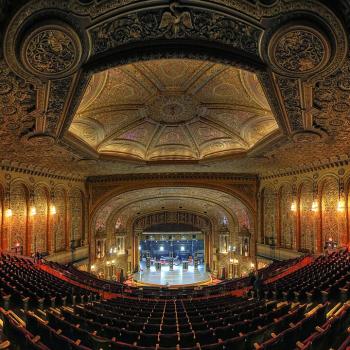

Image: Shrewsbury Abbey today by Michael Beckwith, Flickr, Public domain