Hello again, beautiful creatures.

Amongst witches, magicians, Pagans, polytheists, and other practitioners of a certain age, there’s a line of “getting-to-know-you” conversation common enough to be a cliché which opens with the question, “So, what was your first book?” Many folks commonly cite books by neo-Pagan witches like Scott Cunningham, Marion Green, and Raymond Buckland, or ceremonial magicians like Dion Fortune, Aleister Crowley, and Israel Regardie, even mythologists like Thomas Bulfinch, Edith Hamilton, and my personal favorites, Ingri and Edgar Parin d’Aulaire.

When it’s my turn to play, I usually explain that my first exposure to Paganism, witchcraft, and magic was in the pages of Margot Adler’s Drawing Down the Moon and Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance, which I read simultaneously when I was about 14. It’s a respectable entry point to cite; Starhawk’s Feri-inflected recension of feminist Wicca and Goddess-worship dovetails nicely with Adler’s snapshot travelogue of late 1970s/early 1980s Neo-Paganism, creating a pleasant (if somewhat dated) image redolent of Nag Champa and Polo by Ralph Lauren, perhaps with a Yes album playing in the background.

The trouble is, it’s a false memory. Like many of my contemporary practitioners of the dark arts, I am forced to confess, after all these years, that Jack Chick was right: Dungeons & Dragons led me to witchcraft.

A little backstory may be appropriate at this point.

It was 1981. I was eight years old and in 4th grade, having gone through 2nd and 3rd grades in a single year. I was younger, smaller, and far more insecure than my classmates. I desperately wanted to fit in with them, of course, and my obvious desperation probably had something to do with my social ostracism. (The fact that I was socially awkward and used to thinking of myself as the smartest person in the room probably didn’t help much.)

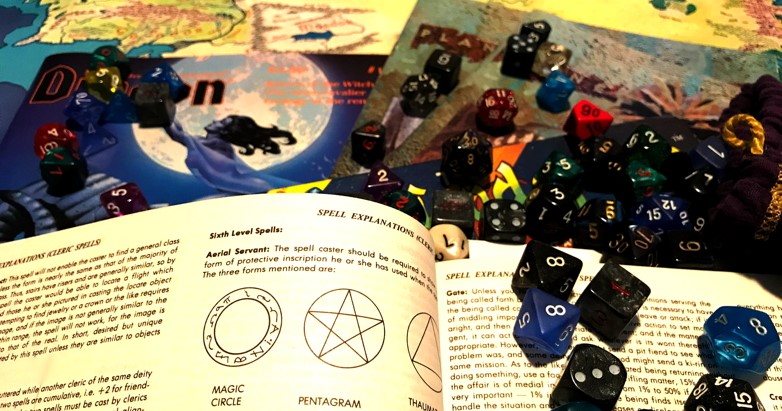

Some of the cool kids in my “gifted and talented” class (just let that sink in for a moment) were really into playing some sort of weird make-believe game that involved shuffling sheets of paper and pencils around, reading from strange-looking books, and rolling polyhedral dice at random intervals. Being the social outcast of the class (let that one sink in for a moment, too), it was several weeks before I finally got one of them to let me in on the secret. I was even allowed to roll up a character of my own: a gnome illusionist who died the moment he entered the dungeon, when the ceiling fell and crushed him into gnome paté. Despite this less-than-illustrious beginning, the game had opened an entire imaginal realm for me, and I was hooked. I raided the school library for books on mythology and fantasy novels, then moved on to my local town library, all the while moping around my house like a miniature Robert Smith until my mother broke down and surprised me with the basic D&D box set and an issue of Dragon magazine.

That was more or less the death blow to any chance I might’ve had for normalcy.

Not by itself, of course. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson’s role-playing game of swords, sorcery, and adventure was brilliant, to be sure, but the portrayal of D&D in Chick’s hysterical Dark Dungeons tract wildly overestimates the extent to which the game draws on real-world occultism. Even in its occasional feinting towards historical magic, D&D tended to get its facts wrong… or, to put it kindly, D&D used bits of historical occultism as window dressing, much as horror films and metal bands tend to. It created a delightfully atmospheric vibe, equal parts Hammer horror and pulp fantasy à la Robert E. Howard or H. P. Lovecraft, but it was a far cry from anything resembling historical thaumaturgy. Anyone who tried to practice magic as outlined in the Player’s Handbook and Dungeon Master’s Guide would find themselves standing in a circle inscribed with meaningless squiggles, holding a handful of tiny balls of bat guano1.

Still, the assembled oeuvre of Gygax, Arneson, et al. pushed my imagination in directions it might never have otherwise travelled. Through their good offices, I discovered the works of Bulfinch, Hamilton, and the d’Aulaires, as well as a host of fantasists whose books would, for better and for worse, form the basis of my teenaged cosmology: Michael Moorcock, Ursula K. Le Guin, J. R. R. Tolkien, the aforementioned Messrs. Howard and Lovecraft, and a host of others. Again, though, these authors weren’t teaching magic and witchcraft in their stories. A great deal of magic can be found in their books, and a careful reader can glean a great deal of spiritual and philosophical truth from their pages (especially from Ms. Le Guin’s Earthsea novels), but they are fictions, first and foremost. They’re no more intended as instructional manuals in the occult than is J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, despite some excitable Christians’ protestations to the contrary. (When a child successfully manages to cast Avada Kedavra, or even Wingardium Leviosa, I’ll be forced to revisit my position, but in the meantime, let’s move on.)

My first real exposure to the occult came not long afterward, though, and from the unlikeliest place I could imagine: my own home library.

___

- Players of 1st edition AD&D with sharp memories may recall that bat guano, mixed with sulfur, was the material component for one of the first truly useful offensive magic-user spells, the ever-popular Fireball.