Move church or any other word through space and time, and you necessarily change its meaning.

The wise Dr. Richard Rohrbaugh, Context Group scholar and compassionate Christian, taught me something crucial for language and religion. Rohrbaugh says,

“Whenever you move the language, you necessarily change the meaning. Whether it’s words or sentences, language only means what it means where and when you use it.”

We’ve talked about this often at Messy Inspirations—it helps explains the name of this blog. This messy principle applies to any word, and no matter how sacred or inspired that word is, it doesn’t contradict the rule.

That includes the word “church,” folks. Watch this video presentation—

Translating Ekklēsia

Open almost any English Bible translation. Almost always, the Greek word ekklēsia has been rendered into the English word “church.” But did “church” exist in the first century? Body of Christ did, indeed. But don’t Catholics, when we use the word “church,” mean something more than just the same Body of Christ spanning the centuries between then and now?

To us, “church” can mean a sacred building in which “church” gathers for worship. Did ekklēsia mean that, way back when?

In fact, as Yves Congar reminded us, the vast majority of Catholics invariably think “hierarchy,” as it has evolved over the centuries, when hearing “church.”

Also, to many Catholic teachers and parish employees I know, the word “church” means a heartless organization of kings who steal wages and force them to work in unsafe situations during a pandemic. Add to that a body of ontologically changed princes or feudal landlords around whom the universe spins.

Defining Church

Congar describes “the church” as, “the whole body, or congregation, of persons who are called by God the Father to acknowledge the Lordship of Jesus, the Son, in word, in sacrament, in witness, and in service, and, through the power of the Holy Spirit, to collaborate with Jesus’ historic mission for the sake of the Kingdom of God” (see “Church: Ecclesiology”).

And for what does this “church” exist? The Second Vatican Council’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church answers: “The church has but one sole purpose—that the kingdom of God may come and the salvation of the human race may be accomplished” (n. 45).

Note the relationship AND distinction between “church” and “kingdom of God.” According to Vatican II, we shouldn’t confuse the church with the final Kingdom of God. Indeed, the church is at best “the initial budding forth” of the Kingdom (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, n. 5). The church and the Kingdom are closely related; they are not identical. “Thy kingdom come” does not mean “thy Catholic Church come.”

The church is not the goal of all history—the Kingdom is. The church exists for the sake of the Kingdom, not the other way around. And given what Congar says about many Catholics invariably imagining Catholic hierarchy when they hear “church,” it is a deadly confusion to neglect the crucial distinction between “church” and “Kingdom.” This is especially true in light of recent criminal scandals creating explosions rivaling those from the Reformation.

Does Ekklēsia = Church?

Should ekklēsia in the New Testament be translated as “church”? Culturally-informed scholars who know better say no.

Even the Catholic members of the Context Group of Biblical scholars consistently avoid using the word “church” to describe any first-century gathering or body. Therefore they never translate ekklēsia as “church.” This is because whenever most people read “church” in their Bible, they will imagine that it refers to some familiar 21st-century social institution. So we might take “church” to mean a building for Christian worship, or a 2,000-year evolved hierarchy, or a group of Trinitarian-monotheistic Christians coming together to worship.

Did any of these realities exist in the first century? If the answer is no, then you should be able to see why it is wrong to translate Matthew 16:18—

And so I say to you, you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church,

Instead, a more accurate translation would be,

And so I say to you, you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my assembly

(or “my gathering” or “my group”).

Jesus Group?

When used in the first century New Testament communities, the word ekklēsia conveys different meanings than those “church” presents to the vast majority of 21st-century people. Therefore, those sensitive to the cultural context will translate ekklēsia, as used by New Testament documents, as “Jesus assembly,” “Jesus gathering,” or “Jesus group.”

Wouldn’t it be wrong and disrespectful to read Paul, or “Matthew,” or Revelation, careless about what these authors were actually trying to communicate? Imagine if we began inserting meanings contemporary to our own social experience into these ancient documents. That would distort these texts, thereby obstructing our understanding and pooling ignorance, no? This is what our botched English translations do every time they render ekklēsia wrongly as “church.”

What Ekklēsia Meant

But what did the Greek word ekklēsia originally mean? Scholars Bruce Malina and John Pilch explain that in Biblical times, ekklēsia referred to a gathering or assembly of summoned people.

By Paul’s day, ekklēsia had acquired two related meanings, each determined by social context, and neither communicating “church” as we understand it. First, ekklēsia meant the process of gathering or actively convening the demos (people). In other words, in a Hellenistic polis (an ancient Mediterranean urban center), ekklēsia was used to describe the active gathering or assembly of politai (property owners with voting entitlements). They gathered into an ekklēsia because they had been summoned (or “called out”) to vote on crucial matters.

But ekklēsia was used according to a second, related meaning by the Greek Septuagint’s ancient translators. There, in their Greek rendering of the mythical Exodus story, ekklēsia translated the Hebrew qāhāl. Both the Greek ekklēsia and the Hebrew qāhāl shared the meaning of a gathering or assembly of people called forth. In the Exodus context, the God of Israel called out Israelites, assembling them to leave Egypt into the limited freedom of serving him.

While in the Septuagint qāhāl is translated as synagōgē or ekklēsia, almost every time after Deuteronomy 5:22, qāhāl = ekklēsia.

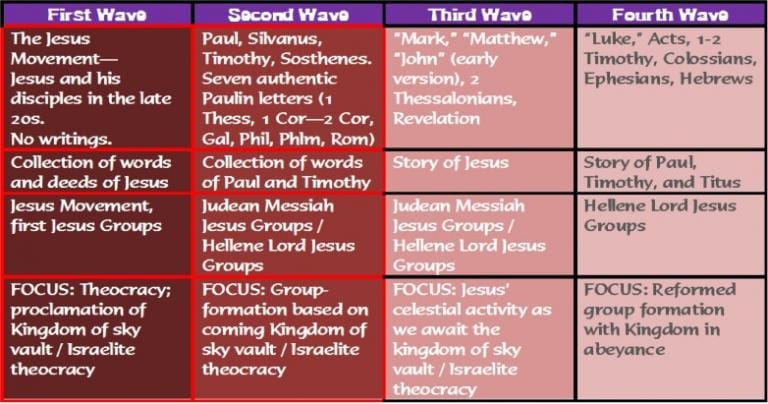

Pauline Jesus Group

Malina and Pilch explain that Paul knew well this understanding of ekklēsia. So too did the audiences o his seven authentic letters. This was because they shared a common Israelite background and knowledge of the Exodus story. If Paul was actually writing to Gentiles, his references would be lost. Thus, as we’ve explained before, Paul evangelized Israelites.

So Paul took these Old Testament meanings of ekklēsia and applied them to his Jesus groups. In other words, Paul understood that Jesus groups, composed of Israelites, had been gathered to respond to the proclamation of the gospel of God. And who summoned or called these Israelites into the Jesus groups? Why, just like in the Exodus, it was assuredly the God of Israel! (1 Thessalonians 4:7; Galatians 1:6; 5:13; 1 Corinthians 1:1-2, 9, 24; 7:15, 17, 20-24; Romans1:6-7; 8:28, 30; 9:24). And just like the Israelites with Moses, the freedom of the Jesus groups is finite liberty to serve the God of Israel (Galatians 5:13).

We should keep in mind that Paul was neither a church pastor nor a bishop. He didn’t care about managing churches or converting individuals. Instead, Paul was only interested in founding Jesus-groups. Through the Jesus group, an individual Israelite passed, and this Jesus group existed for God through Messiah Jesus. “Religion” is the community’s business. None of this should surprise us if we understand the collectivistic nature of the circum-Mediterranean world.

So, Take Care with the Bible Translations!

Because the meanings of all words and language derive from social systems, be careful when encountering “church” in the Scriptures. Don’t buy Bible translators, interpreters, and popular Catholic speakers when they assert that “church” is to be found in the New Testament. They are being anachronistic. To say otherwise is false, historically inaccurate, and pools ignorance, often in favor of triumphalism. Ultimately, you won’t be able to find “church” anywhere in the first century Mediterranean.

Ekklēsia changes meaning throughout the New Testament literature and patristic literature. Still, the purpose is never “church” as we understand it. Only when Constantine formally accepted Christ Jesus and Jesus-group leadership do we discover the origin and rise of Christendom, the Christian political religion. Therefore, don’t use “church” for anything prior.

Apostolic Church?

The oak and the acorn are related, and one does spring from the other. Can it be truthfully said that our churches are in continuity with the earliest Jesus groups? Yes, provided we mean by “continuity” always a continuity-within-development. That essential developmental aspect does not demand that what evolved later wasn’t God’s will or incorrect. But we ought to be honest enough to recognize that not everything that developed after was good and God-authored.

I’ll give one example.

Wherever and whenever authority is exercised, it must be exercised in the manner of Jesus, who came and lived as one who serves (Mark 10:45). Whenever we detach Church authority from this holiness of service, we’ve ruptured continuity with Christ and his apostles and committed a blasphemy. Whenever Church authority seeks to coerce and therefore places itself above the grace of the Holy Spirit, it is a blasphemous mockery of Christ and the apostles.

The situation with the ongoing McCarrick scandal and John Paul II is such a blasphemy on the Body of Christ.