Fellowship with sinners is justified by the Lukan Jesus.

Yesterday we began exploring Jesus’ explanation for his table fellowship with sinners in the Gospel from this past Sunday according to the Common Lectionary.

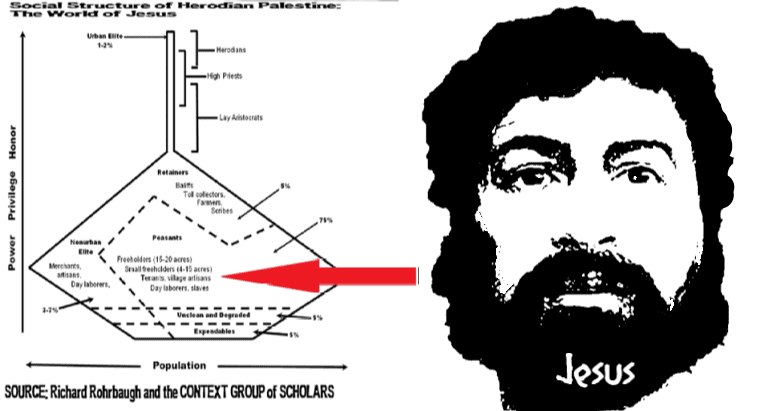

The parable of the Two Lost Sons (often misnamed “The Parable of the Prodigal Son”) is unique to “Luke.” Regardless of whether the historical Jesus actually spoke some primitive version of it or not, the story as is presents a situation that Galilean peasants in the 20s CE would be all too familiar. Cities were filled with urban poor who were actually displaced villagers separated by family conflicts and debt foreclosure of lands. The story is remarkably honest to the life situation of Jesus and his fellow peasants.

Fellowship with Sinners

The story evokes many things. It celebrates efforts to cancel debts and reconcile. A cautionary tale, it questions the addictive pattern poor peasants have for the city and exposes the failed patronage, and dangers, there.

And yet, as we indicated yesterday, the parable is not really about repentance and forgiveness. This story, along with the parables of the Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin are given against this backdrop—

Luke 15:1-2

The tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to listen to him, but the Pharisees and scribes began to complain, saying, “This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.”

Let’s see how the author we call “Luke” develops this theme of table fellowship with sinners through the first two parables in chapter 15.

Those Who Balk at Fellowship, Jesus Insults!

What we find throughout Luke 15:1-32 is a rather insulting response to the challenge of the insulting commentary from the Pharisees and scribes, vv. 1-2. That Jesus was welcoming sinners means that he was sharing meals with them (i.e., table fellowship, see Mark 2:15; Luke 10:8). Jesus was honoring throw-away people—he respected them, accepted them, trusted them, and shared his peace with them as if they were his kin. All this is meant by Mediterranean, Middle Eastern table fellowship.

The never-nice, cleverly impolite Jesus, Middle Eastern Master of the Insult, enrages the Pharisees and Torah-experts. He does this because he welcomes sinners to the table. The perspective of Jesus’ adversaries was that to eat and drink with sinners brings shame, even though feeding them acquired honor. There can be no fellowship with sinners!

By the third century, teachers in Rabbinic Scribalism had discerned that since a host could control the meal, its actions, and food-purity, it was preferable to host questionable people than to be hosted by them (m. Demai 2:2-3). And yet this warning, interpreting Exodus 18:1: “Let not a person associate with sinners even to bring them near to the Torah” (Mekilta 57b).

Regardless, it was always perilous to host toll collectors. This was because making your home vulnerable to these retainers exposed all your possessions to their touch as they calculated the value of everything.

Comparing Them to Shameful Shepherds

The Lukan Jesus tells the Pharisees and scribes the Parable of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:3-7), thereby insulting them by comparing them with shepherds. Pharisees loathed the shepherds, people who were universally seen as crooks in the first century Mediterranean.

Because of our Christmas traditions, 21st century Western Christians tend to romanticize biblical shepherds. True, in earlier times, this had been an honored profession associated with great Israelites—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and his sons, Moses, and David had all been shepherds.

But by the time of the first century, things had changed. Shepherds were thought of as thieves who did not respect the boundaries of fields, allowing their flocks to graze on others’ lands. They were also considered a shameful lot because they left their women unprotected while out at night with their flocks. In Jesus’ day shepherds were counted among the despised occupations—camel and ass drivers, tanners, butchers, and sailors.

When the Johannine Jesus calls himself “the Good Shepherd,” that is a very jarring oxymoron! Consider this in this Gospel story from “John” this past Easter Season…

Lost Sheep and Shepherds

By saying to them, “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep…,” the Lukan Jesus insultingly invites his enemies to picture themselves as despised and dishonored shepherds. The Lukan Jesus’ question to the Pharisees drips with insulting sarcasm.

Even the largest landowning peasant in first century Galilee would not own more than forty sheep. Perhaps what is being implied in the story is that these one hundred sheep are owned by more than one family, or an extended kinship network. If a sheep is lost, the cost is borne by the poor shepherd.

The Limited Good and Lost Sheep

Also: when one considers the peasant view of the Limited Good, and that ancient Israelites saw life as a zero-sum game, the story becomes more interesting. The prevailing idea was when something gets lost it is gone for good! So if someone claims to have found a lost sheep, since a lost sheep ought to be lost forever according to the view, the understanding was this sheep had to have been stolen from someone else. In the world Mediterranean peasants, someone’s gain is always someone’s loss.

These last two points help explain the need for a celebration far more costly than a single sheep. On the one hand a community celebration upon finding the sheep makes sense between this shepherd and his fellow shepherds. The Greek suggests that males celebrated this happy event, as the words “friends” (φίλους) and “neighbors” (γείτονας) here are masculine (Luke 15:6). But the shepherd who lost and found the sheep would be initially suspected of theft. So he must spend more than the sheep in convincing his brothers that this indeed was the original beast.

Unthinkable Insult: Comparing Them to a Woman

If the Lukan Jesus had bluntly asked his adversaries, “Which one of you women…?” they would have attempted to murder him on the spot. Such a comparison would demand immediate and violent retribution in defense of honor in the world of the Bible. So the Lukan Jesus instead asks, more generally and softer, “Which woman having ten coins and losing one…?” (Luke 15:8-10)

The lost sheep in the previous parable was a community’s loss. But the lost coin in this parable is a person’s loss. It needs to be found and returned to her clothing, an ornamentation of jewelry. It is equivalent in cost to a denarius, or the Roman Empire’s standard silver coin (Mark 6:37; 14:5).

Bruce Malina and Richard Rohrbaugh explain that a denarius was a standard day’s wage in the first century (Matthew 20:9, 10, 13). These scholars also explain that three thousand calories for five to seven days, or 1,800 calories for nine to twelve days, for a family of four adults, would be provided by two denarii (Luke 10:30). Or a poor itinerant could buy 24 days of bread for the same, two denarii.

These peasant homes were dark, without windows. Hence, lighting a lamp would be necessary to find the coin.

In contrast with the male friends and neighbors of the shepherd in the previous parable, the woman calls her female “friends” (φίλας) and “neighbors” (γείτονας), and the Greek words are feminine (Luke 15:9). Calling them all to celebrate the wonderful fortune of something that should be lost forever signals she can be trusted that she did not steal the coin from someone.

Joyous Stories, Upset Pharisees

Why are the Pharisees and scribes so upset seeing Jesus’ Table Fellowship with those whom their society excludes as sinners? The stories explain that when a diligent search happens, something treasured that has gone missing is found, and the result is joy.

Jesus enjoys shared community with those he has socially healed. The formerly lost, now found and restored, sit at table together with Jesus. Shouldn’t the Pharisees be overjoyed at those lost being found and healed? Instead they are furious, disappointed, upset.

Add to this another double-parable, that of the Lost Sons, and something of a dire warning is given concerning attitudes that block out the unitive work of healing.

Sad Story

These stories of Luke 15 are all about Jesus having table fellowship with the wrong sorts of people. As I have said before, the Bible gives us no marching orders or direct answers for human life today. And yet, perhaps sacramentally and indirectly, one can find through prayerful grappling a direction…

Although these situations and social structures are not ours in the 21st century West, one can find many people, including authority figures in hierarchical positions in the Church, who continually make religion into a game of who belongs and who doesn’t, who gets in and who doesn’t, who is worthy and who isn’t, who can commune and who can’t. They think they are the gatekeepers to table fellowship with Jesus. Are they?

As the brilliant Mary Pezzulo reminded us on her blog, this past Sunday was Catechetical Sunday. The theme was Stay With Us. Honestly, it sounds a tad desperate, folks. We forget that even though our Church’s sacramental celebrations may be compared to a fountain, the whole atmosphere of earth is full of water. Doesn’t the word “catholic” allude to that? Life-giving water isn’t limited to only the explicitly Catholic places or dispensers!

Is there joy at the fountain? Do we welcome the thirsty, recognizing our thirst in theirs in empathy as a listening Church? Or do we stand at the door ordering people as police allowing only the pure and perfect to enter?

When you see someone going up for Communion, how flows the joy in you?

Tomorrow we will conclude this exploration by looking closely at the narrative of “Luke” by way of the previous three Sunday Gospels in the Common Lectionary.