Confusion abounds throughout history for the notoriously difficult Parable of the Dishonest Manager, inscrutable even to the Evangelist “Luke”!

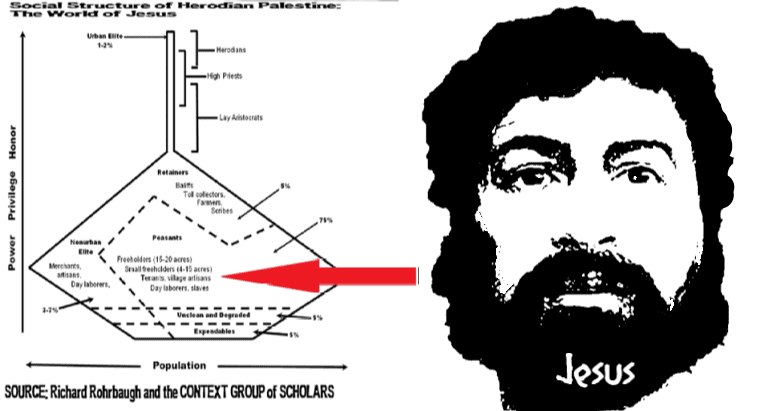

There should be no confusion that the historical Jesus, unlike the Jesus depicted in the Fourth Gospel called “John,” certainly told parables. These parables are all from Jesus’ ancient, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean context. Peasants, like Jesus the village artisan (definitely not the “intellectual sage” we Westerners idolize), are good storytellers. Therefore, parables are a great folk medium. And thus they are extremely difficult for 21st century Westerners to grasp despite all the spurious familiarity American Christians can bolster.

None of Jesus’ stories are so perplexing to us Western people as the one from this past Sunday’s Gospel, Luke 16:1-13. Most confused and troubled of all are Western Christians of a capitalistic bent. It’s baffling! The confusion about it is great.

What the hell did Jesus mean by this story when he told it? Keep in mind that this is a story where a dishonest steward defrauds his master and gets commended! In the end, he comes out on top! Is Jesus telling us to emulate this man? What kind of lesson would that be, true believers?

Inscrutable Confusion about the Steward

The Parable of the Shrewd Steward takes the cake for being the most confusing and difficult to understand (for Western readers anyway) parable of Jesus. I0 Opinions on it throughout two millennia are wildly and widely different. Confusion over it has always been with us. It was found to be strange and difficult to both ante-Nicene Jesus groups and post-Nicene Christians.

But most shockingly of all, this strange parable confounded even the evangelist we call “Luke,” the author of the only document in which we find it. This is clearly seen by his tagging onto it four different and contradictory endings. Each of those punchline-endings completely changes the story and none of them could have been attached to the parable in its original form! Each of them is alien to the Galilean life of Jesus.

Long before capitalism was born, no one knew how to handle this parable. Why would Jesus commend a dishonest servant?

First Century Confusion—A Different Economic Situation

Jesus’ world was agrarian, quite alien to anything from our post-industrial society. The economy that Jesus and his contemporaries knew, embedded as it was in either politics or kinship, was agricultural. To attempt a contrast in the Biblical world between our 21st century categories of “industry” and “agriculture” would be futile. It would likewise be pointless to contrast “poor” and “rich,” or “rural” and “urban” as we understand these terms.

To understand the world of Jesus and his situation, we must inquire as to who had mastery over the land and its agricultural yields, and who controlled the surplus?

Jesus’ Good News has to do with this stuff. Ask yourself: what would “Good News” look like to village peasants such as Jesus? What Jesus was proclaiming by “Kingdom of God” (or the more politically correct “Kingdom of Sky Vault”) was theocracy. That’s a longtime popular idea in the Middle East. When you have a society that claims to be governed and ruled by God, that’s theocracy (see Iran). That’s what Jesus was all about, my friends.

Look to the crucifix to see the (albeit sanitized) result of Jesus’ proclamation. Do you imagine that such a horrific outcome follows a proclamation about something metaphorical? Did the Romans destroy people in this fashion, in the most humiliating status-degradation ritual conceivable to Mediterraneans, for metaphors? Did they crucify Jesus for a 19th century “spiritual” message? Friends, Jesus crucified is a political payment for a costly, political proclamation: Israelite theocracy.

Let’s break down the characters from the parable of this past Sunday’s Gospel.

Confusion of Characters: The Master

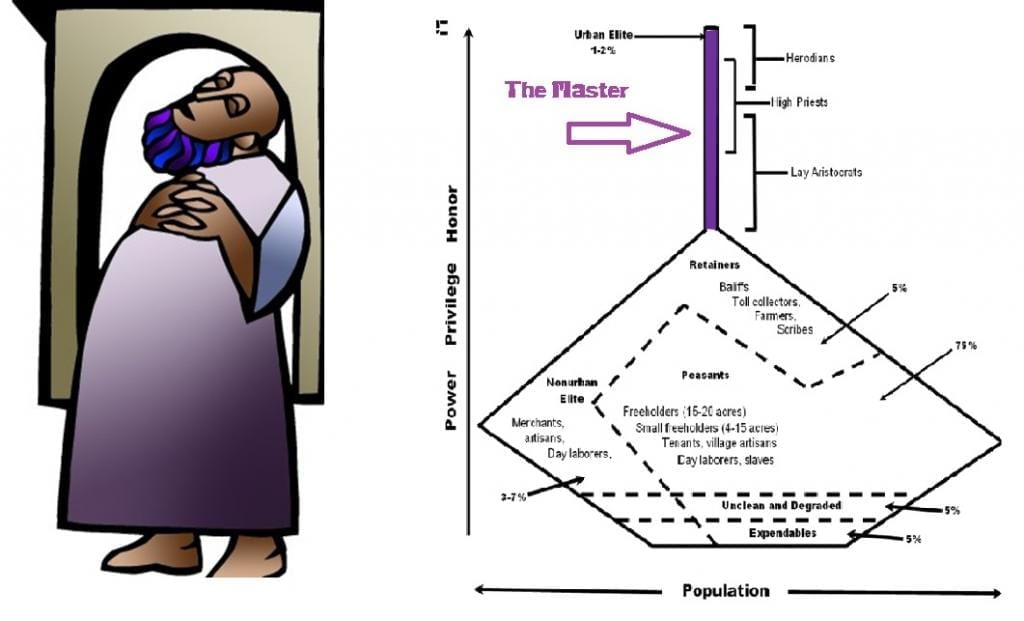

The master in the story (16:1) is a landowner who is called “a rich man.” He belongs among the urban elite, one to two percent of the population of Roman-controlled Syro-Palestine. Whenever you see “rich man” in your English Bible, scratch it out and write in “greedy man.” “Rich” in the Bible—or anywhere in the ancient Mediterranean—evokes a social code. The “rich” are those who stand against the interests of peasants.

Consider: if Jesus was telling this story about a “rich man” primarily to a starving Galilean peasant audience, what do you think would be their reaction? Peasant villagers would understand this greedy man—one who refuses to be a patron and share his surplus—to be a shameful villain.

Confusion Concerning the Steward

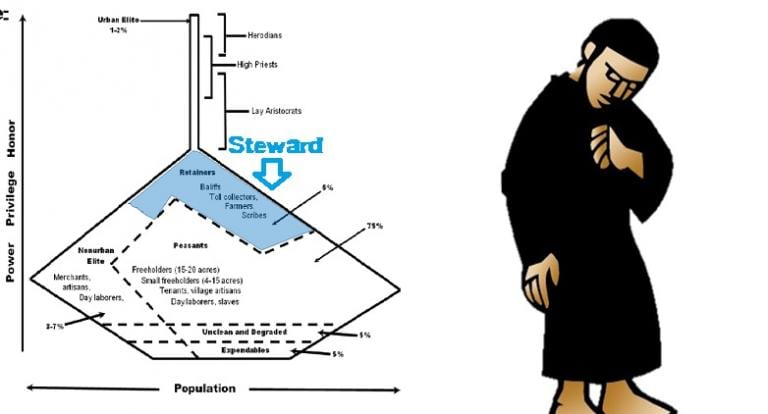

A steward manages the agricultural production of the greedy master’s property. Stewards belonged to the retainer class, about five percent of the total population. They had massive responsibilities and were constantly being scrutinized. To be a steward was a dangerous occupation in the ancient world—debtors and tenants could destroy you with gossip and slander.

Despite the troubles endured by all stewards in their difficult employ, don’t expect any sympathy for them from Jesus’ peasant audience. After all, stewards represented the greedy city-dwelling elites who stole their ancestral lands via debt foreclosure. In the world of the Bible, a man’s representative is to be seen as the man himself. So it’s likely that Jesus’ peasant hearers would think negatively about this character as well.

Confusion about the Debtors?

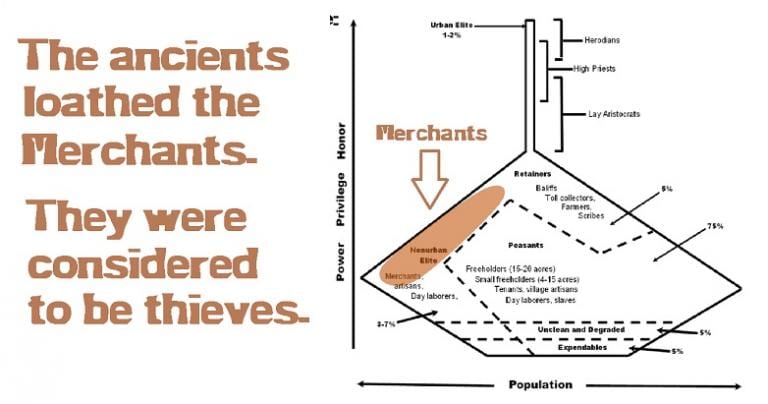

The debtors in this story cannot be peasants. The amount of their debt is 20 times the usual peasant family lot and no peasant owned 200 acres of land. Their rent is about 900 gallons of oil and 150 wheat-bushels, which implies vast olive groves and fields. The average peasant plot was between one and six acres. The cumulative debt of these people would be that of an entire village!

Who were the debtors, then? They had to be merchants, people detested by all ancients, including peasants. Merchants were seen universally as greedy thieves. Although not elites and loathed by everyone in the biblical world, merchants nevertheless did have access to wealth and owned lands. Here also don’t expect any sympathy for the debtors by Jesus’ peasant audience.

So far the story has given us 1) a greedy SOB landowner, 2) a steward who represents that bastard, and 3) greedy, lying, thievish merchants who are in debt to the wicked landowner. So far so good?

Breaking Down this Story of Confusion

People report to the master that his steward or estate manager has been squandering his property.

Luke 16:1

A rich man had a steward who was reported to him for squandering his property.

The steward is fired on the spot and commanded to give a full accounting—

Luke 16:2

Prepare a full account of your stewardship, because you can no longer be my steward.’

Things look terrible for the steward. What will he do now?—

Luke 16:3

The steward said to himself, ‘What shall I do, now that my master is taking the position of steward away from me? I am not strong enough to dig and I am ashamed to beg. I know what I shall do so that, when I am removed from the stewardship, they may welcome me into their homes.’

Things could be much worse, however!—that he is simply dismissed is a great fortune. Scholar John Pilch informs us that should there be losses to the employer, the agent must pay them. But instead of being fined or thrown into prison, the manager is simply dismissed from his position. In a way, the greedy landowner has acted mercifully toward this miserable steward.

The Steward’s Scheme

Nevertheless, the situation is still dire, and the steward grapples with what to do. Although his dismissal is immediate and all his agency and privileges over affairs are gone, in this age before telecommunications, he still has some time before news of his removal (and shameful ruin) hits the fan. So, cleverly, he concocts a plan.

Shrewdly, the steward summons all of his mater’s debtors, “one by one.” He inquires about their enormous debts. Then he cancels huge portions of what they owe. In effect, he is giving away his FORMER master’s wealth. This dishonesty and fraud is coupled with the reality that his position of management has been removed!

And on discovering this, what does his master do? Does he have this wretch seized and thrown into prison? Does he murder him on the spot for this theft and malfeasance? Nope. Rather, the landowner commends the steward for his prudent actions.

Luke’s Confusion

Why would the Master do such a crazy thing? And why would Jesus tell this story? What does it all mean?

More than likely, in its original form, this was the ending of the Parable of the Shrewd Steward. Recall what we said earlier about introductory and concluding statements to parables in the Gospels. These were certainly invented after Jesus and added at a later stage of development.

“Luke” clearly did not understand this story. But to honor Jesus, he included it. But he added no less than four different and contradictory concluding statements to it! Assuredly, these later additions cannot be traced back to Jesus when he actually told an earlier version of this story.

Fourfold Confusion of Concluding Statements

Why did the Evangelist named “Luke” stick “concluding statements” onto Jesus’ parables? And where did these punchline “morals of the story” originate?

Scholars believe that the concluding statements represent to each Evangelist the meaning of the story. This is just like preachers today with Jesus’ stories. They tell us what they mean—or rather, what they THINK they mean. Two different preachers preach the same parable, and often, you get completely different meanings. We’ve had that since Day One in the Church, folks. It’s not difficult to demonstrate, either.

As we saw with the Parable of the Banquet, different and contradictory concluding statements got pasted onto the parables. The Parable of the Banquet is one story—but history records three different punchlines which totally change the story! The parable being told within different places and times made this happen. Homilists and preachers unwittingly maintain this most ancient tradition down to this very day.

Just like the author we name “Luke” collected stories and saying of Jesus, so too he collected punchlines. Long before he included it in his Gospel, earlier preachers had used it in the Jesus groups and had probably invented these punchline endings. Each likely represents a different, forgotten preacher and what he thought the meaning of the story was. “Luke” didn’t understand this parable—but he did know of four proposed “meanings” to it. So, he added all four.

First Confusing Punchline: Messianists are Dumber

With the help of Dr. Richard Rohrbaugh and his fellow Context Group of Biblical Scholars, let’s examine the different punchlines. Here is the first proposed meaning to this parable—

Luke 16:8b

“For the children of this world are more prudent in dealing with their own generation than are the children of light.”

Essentially this goes something like, “You followers of Jesus are not as bright as other people.” Does that shed any light on the parable or help us to understand why Jesus would commend the unjust manager?

Second Confusing Punchline: BE Like the Shrewd Steward!

The first explanatory comment didn’t explain much, so “Luke” adds a second punchline—

Luke 16:9

“I tell you, make friends for yourselves with dishonest wealth, so that when it fails, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.”

This conclusion is less helpful than the first punchline, even though it implies that followers of Jesus should behave as the Steward did. Perhaps a cultural truism about how everything in Mediterranean life depends on social networks and making friends, it is not clear how this helps the parable become intelligible or prescribe a way of life. And was Jesus telling this story about “eternal dwellings”? Can you win “eternal life” by cheating your employer? In what way are we to be like the Shrewd Steward?

Third Confusing Punchline: DON’T Be Like the Unfaithful Steward!

Indefatigably, “Luke” attaches a third, somewhat complex punchline—

Luke 16:10-12

“The person who is trustworthy in very small matters is also trustworthy in great ones; and the person who is dishonest in very small matters is also dishonest in great ones. If, therefore, you are not trustworthy with dishonest wealth, who will trust you with true wealth? If you are not trustworthy with what belongs to another, who will give you what is yours?”

Here we have another preacher who would definitely not recommend behavior like the steward whom he considers “unfaithful.” We seem to have another truism in the opening sentence, but what does that have to do with this story? His two questions at the end might be good folk wisdom, sure, but it has nothing to do with this parable! And if this is the concluding remark, well, it sucks.

The Final Confusing Punchine: Only Enough Love for One

Zero and three, “Luke” adds one final punchline.

Luke 16:13

“No servant can serve two masters. He will either hate one and love the other, or be devoted to one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.”

Those are not bad ideas. Earlier we discussed the peasant notion of the Limited Good, and such a statement would make a of sense to those holding such an outlook. In the world of the Bible, there is only so much love to go around. Love is a limited supply in the Bible, folks. Go ask Esau about that.

Despite being culturally-relevant wisdom, it’s too bad that proposed meaning also has nothing to do with Jesus’ parable.

Why Luke’s Confusion?

As we noted before, Jesus told versions of the stories in a certain way, within a particular context, somewhere in the first century Galilee. But they moved and were impacted by people experiencing the Risen Jesus, established by the God of Israel as Cosmic Lord and Messiah. When these stories moved beyond Easter in time and Syro-Palestine in place their meanings necessarily changed.

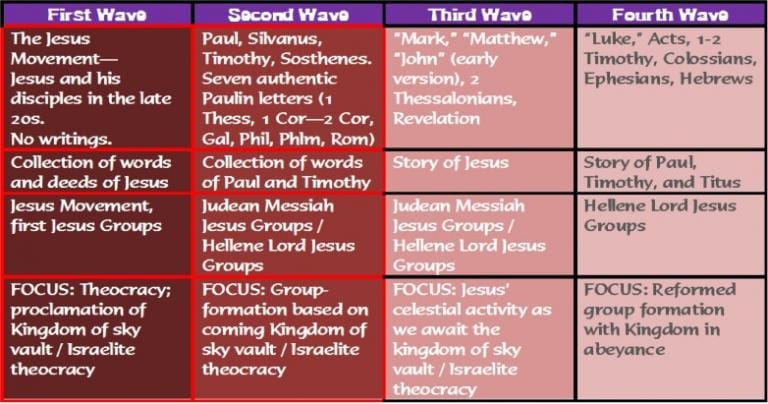

Again, Galilean peasants like Jesus were illiterate. No matter how much we desire to morph Jesus into an American Intellectual Sage or Greco-Roman Sophisticate, the First Wave of the Jesus Movement was an illiterate generation. Only two percent of Jesus’ society were able to read and write. Jesus and the vast majority of his original audience simply were outside that circle.

Socio-Economic Confusion

So when we reach the literate stage of the Jesus Tradition, something amazing happened. We have crossed an immense social chasm from Galilean peasantry into those with elite social status. This also constitutes a shift in meaning. As we said before, interpreting Jesus, the perspective of Mediterranean elites would necessarily differ from his earlier peasant contemporaries.

Wholly different crises occurred at different times throughout the three stages of Gospel development. The social reality of those Galilean day laborers in the Jesus Movement was quite different as those tasted by later Hellene Lord Jesus Groups.

Early Jesus Groups, like the one to which “Luke” belonged, simply did not understand Jesus’ parables adequately. “Luke” was distant from the Galilee of Jesus, removed from peasant life there. He was therefore unfamiliar. But this anonymous and elite Hellene Israelite scribe gave his very best to pass on the words of Jesus.

More to Come

Later this week we will conclude our exploration of the Parable of the Shrewd Steward (or Dishonest Manager?). Using the wisdom of Dr. Richard Rohrbaugh and the Context Group of Biblical Scholars, we will see that honor is the key cultural value which helps unlock its meaning.

Image by Robin Higgins from Pixabay