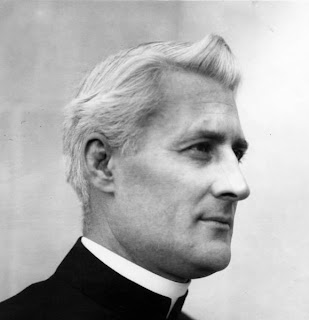

He looked like a movie star, and John Markoe’s life would make a pretty good movie. Born to a blue-blood Philadelphia family in 1890, he left home after high school to work on the railroad out west. He came back when he was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He played in the 1913 Army-Notre Dame game that saw Knute Rockne’s forward pass. He graduated with the Class of 1915, known as “the class the stars fell on.” (Fifty-nine of the 164 graduates became generals, including Markoe’s lifelong friends Dwight D. Eisenhower and Omar N. Bradley.) After graduation, he was posted to a Black cavalry regiment on the Mexican border, but heavy drinking cost him his commission. He then went to Minnesota where he worked as a lumberjack and joined the National Guard. During the undeclared war with Pancho Villa in 1916, he won back his commission, but by then he had sight on different goals. In 1917 John Markoe joined the Missouri Province of the Jesuits, a step his brother Bill had taken a few years earlier. Not long thereafter the Markoe brothers took a pledge to “give our whole lives and energies to the salvation of the Negro in the United States.” His attempts to integrate St. Louis University during the forties earned him the enmity of local church authorities, and he was “exiled” to Creighton University in Nebraska, where he taught math. Creighton was a city with a growing African-American population, and segregation was in full swing. Markoe played a leading role in forming the DePorres Club at the university, “to educate people to think along the lines of charity and justice as regards inter-racial matters.” One Creighton alumnus said of Markoe: “His utter conviction that civil rights was what we should be doing kept us going.” The Jesuit often said: “Racism is a God Damned thing. And that’s two words: God Damned.” From the 1940’s on, the club was organizing sit-ins and boycotting railway companies, organized protest marches. They even forced the city’s Coca-Cola plant to accept Black applicants. Not long before Markoe’s death in 1967, John Howard Griffin, author of Black Like Me, said that the Jesuit was “in the cauldron when most of us were in diapers.”