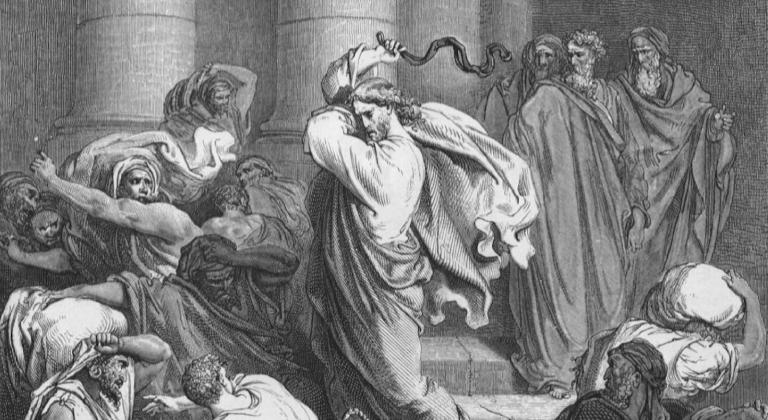

Ours is a civilized god. He is distant, floating high above the world, refusing to be dirtied by it. He is the Supreme Hierarch, the Ruler of All. The Great Architect, looking down over all of creation and ordering it according to his Divine Blueprint. Of all of the things he’s created, he likes human beings the best. Sometimes he communicates to some of these humans, revealing to them part of his Divine Blueprint. Our primary relationship with this god is one of obedience; we are to do his will so that things can work according to the Blueprint.

This god works well with imperialism. Imperialism is about ordering creation. It is about obedience. It is about mastery. This god is the creation of an imperial imagination.

The god we have shaped in our image has re-created humanity. We too live above the world, separate from it. As abstracted from it as our god is from us. We live in a world of distances…where humanity is separated from God, where person is alienated from person, and where we have forsaken our creatureliness to rule creation. Ours is a lonely world.

In order to make sense of our chaotic, lonely world, we create blueprints of our own, and try to control what is around us to conform it to that blueprint. We do this because we worship a blueprinting god. Insofar as we worship this god-with-a-blueprint whose first requirement is obedience (understood in its traditional, monological sense), we place ourselves in a story of imperialism.

Some may balk at this. Many Christians, after all, have found a way to worship a god who demands obedience while, at the same time, live in ways of mutuality, love, and humility in their own lives. Nevertheless, I suspect there is an unresolved tension within their minds and hearts: why does this god act in one way and then call me to another?

In the end, they accept some sort of Divine Exceptionalism. Much like the United States (or any other Empire) holds itself to a different standard than subordinate nations, so too this god can commit acts of genocide, violence, and oppression while (without any sense of irony) tell us to love our enemies, turn the other cheek, and practice mutual submission. It is one step from worshiping such an exceptional god to embracing imperialism in his name.

Before I go further, I want to clarify a bit what I’m getting at when I say “obedience.” I’m not encouraging divine disobedience (not exactly). Rather, I’m advocating for a reimagining of what obedience looks like. And a re-imagining of our image of God. I believe God’s concern is primarily for us to be like Jesus, not simply to act like Jesus through obedience.

John 15 (where Jesus says, “I no longer call you servants”) seems to point in a direction that challenges conventional notions of obedience. It is interesting that Jesus says, in the same breath “I no longer call you servants” and “if you obey my command you are my friends.” This seems kinda strange, until you examine the nature of the command: to love.

Here Jesus is offering an understanding of obedience that is different. It is no longer monological (I say and you do), but dialogical (we are now friends). Just as the lordship of Jesus subverts our notions of reign, so too does Jesus’ call to obedience subvert our notions of obedience.

When you have a lord who undoes lordship and a master who subverts mastery, then everything is different. I think it is a mistake to assume that obedience to such a One is at all similar to other patterns of obedience.

This line of thought is hardly original. I first encountered such unsettling (and liberating) thoughts in the writings of Dorothee Sölle, who writes:

Can one demand a particular stance toward God and educate toward that stance, yet simultaneously criticize that same stance toward people and toward institutions? Is it actually possible, in the realities of daily life, to distinguish between the obedience which is due God and that obedience toward people which we can and ought with good reason refuse? I suspect that we Christians today have the duty to criticize the entire concept of obedience, and that this criticism must be radical, simply because we do not know exactly who God is and what God, at any given moment, wills. It is no longer possible to describe our relationship to God with a formal concept that is limited to the mere performance of duties. We cannot remove ourselves from history if we wish to speak seriously about God. And in our Christian history, our history of the 20th century, obedience has played a catastrophic role.¹

Sölle isn’t suggesting the abandonment of obedience, as though we should rebel against God. Rather, she suggests a re-examination of obedience in light of Jesus’ witness:

[Obedience] does not mean the carrying out of commands, and most assuredly not in the sense of Benedict’s continually repeated decision to obey the abbot the way Christ obeyed God. Obedience means instead a decision which first discovers God’s will in doing. The person herself must decide what is to be done; she is not the fulfiller of assigned commands. Nothing is here taken from the autonomy of the subject. The will of God does not present external demands and it is not predetermined or fixed…It is not God in a general, timeless sense who demands obedience, but the situation which demands a response, and only therein does God require a person’s response…an obedience which has its eyes wide open, which first discovers God’s will in the situation, a discerning obedience.²

Our relationship with God shapes our relationship to one another and to the land. If that relationship is seen primarily as that of subjects to the Supreme Hierarch, our imaginations will tend towards imperialism.

- Dorothee Sölle, Beyond Mere Obedience, New York: The Pilgrim Press, 1982, p. 10

- Sölle., p. 24-25.