The Catechism tells us that Scripture has different layers of meaning:

115According to an ancient tradition, one can distinguish between two senses of Scripture: the literal and the spiritual, the latter being subdivided into the allegorical, moral and anagogical senses. The profound concordance of the four senses guarantees all its richness to the living reading of Scripture in the Church.

116The literal sense is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation: “All other senses of Sacred Scripture are based on the literal.”

117The spiritual sense. Thanks to the unity of God’s plan, not only the text of Scripture but also the realities and events about which it speaks can be signs.

1. The allegorical sense. We can acquire a more profound understanding of events by recognizing their significance in Christ; thus the crossing of the Red Sea is a sign or type of Christ’s victory and also of Christian Baptism.

2. The moral sense. The events reported in Scripture ought to lead us to act justly. As St. Paul says, they were written “for our instruction”.

3. The anagogical sense (Greek: anagoge, “leading”). We can view realities and events in terms of their eternal significance, leading us toward our true homeland: thus the Church on earth is a sign of the heavenly Jerusalem.

118A medieval couplet summarizes the significance of the four senses:

- The Letter speaks of deeds; Allegory to faith;

The Moral how to act; Anagogy our destiny.119 “It is the task of exegetes to work, according to these rules, towards a better understanding and explanation of the meaning of Sacred Scripture in order that their research may help the Church to form a firmer judgment. For, of course, all that has been said about the manner of interpreting Scripture is ultimately subject to the judgment of the Church which exercises the divinely conferred commission and ministry of watching over and interpreting the Word of God.”

- But I would not believe in the Gospel, had not the authority of the Catholic Church already moved me.

Just how ancient is that tradition? We’re talking ancient as Jesus (at least). So Jesus and the apostles are constantly looking at the Old Testament and seeing secondary meanings there. The manna is a sign pointing to Jesus, the Bread of Life (John 6), according to Jesus. Likewise, Jesus sees the Bronze serpent as a sign pointing to his crucifixion (John 3:14). The Tabernacle is a sign pointing to, well, lots of things according the whole book of Hebrews, which is all about interpreting those signs. Paul say the passage through the Red Sea is a sign of baptism. Indeed, whenever the New Testament looks at the Old, it is never interested in the literal sense of the Old: it always looking for some symbolic meaning.

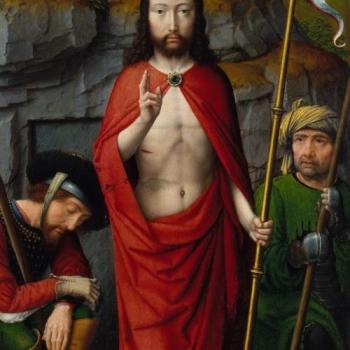

The apostles do that for a simple reason: they were told to by the Risen Christ:

“These are my words which I spoke to you, while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the law of Moses and the prophets and the psalms must be fulfilled.” Then he opened their minds to understand the Scriptures, and said to them, “Thus it is written, that the Christ should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead, and that repentance and forgiveness of sins should be preached in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses of these things. And behold, I send the promise of my Father upon you; but stay in the city, until you are clothed with power from on high.” (Lk 24:44–49).

So that’s what they did. When they read the Law and the Prophets they expected to find Jesus and his gospel hidden there, and they did.

The reason they expected to find him there was because his Spirit had inspired Moses and the prophet and he had taught them in a bunch of ways already some of the ways to see him there. The water from the Rock was a foreshadow of the Spirit poured out in the waters of baptism from Christ’s pierced side. The Temple was the sign of the body of him who said “Destroy this temple and in three days I will raise it up.” The Blessed Virgin was overshadowed by the same Cloud of Glory that overshadowed the Ark of the Covenant.

So it’s no big surprise that Jesus’ talk would be chock-full of allusion to biblical imagery from the Old Testament and he would expect his disciples to connect the dots. Take Isaiah 22:

Thus says the LORD to Shebna, master of the palace:

“I will thrust you from your office

and pull you down from your station.

On that day I will summon my servant

Eliakim, son of Hilkiah;

I will clothe him with your robe,

and gird him with your sash,

and give over to him your authority.

He shall be a father to the inhabitants of Jerusalem,

and to the house of Judah.

I will place the key of the House of David on Eliakim’s shoulder;

when he opens, no one shall shut

when he shuts, no one shall open.

I will fix him like a peg in a sure spot,

to be a place of honor for his family.”

In the Davidic kingdom, the master of the palace was a sort of prime minister or major domo figure, overseeing the House of David. Shebna was doing a crummy job, so God replaced him with Eliakim and gave him (SIGNIFICANT BIBLICAL IMAGE ALERT!) the “key of the house of David”.

If that image of “the keys of the kingdom” sounds vaguely familiar to you, that’s because you are already making use of the Senses of Scripture the Catechism talks about and are thinking biblically.

Because yes, in Matthew 16, Jesus, the New Davidic King (they don’t call him “Son of David” for nothing) alludes clearly to this image when he says:

“Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah.

For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my heavenly Father.

And so I say to you, you are Peter,

and upon this rock I will build my church,

and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it.

I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven.

Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven;

and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

There’s just ever so much verbal play at work here. First, of course, is the changing of Simon’s name to Peter. What you are looking at there is a translation. “Peter” is the Greek form of the name Jesus gave him in Aramaic: Kefa (you can see a sort of transliterated form of it in Paul and in John’s gospel: “Cephas”. “Peter” is the Greek for “Rock”. “Cephas” is just how you pronounce “Kefa” if you are a Greek speaker. To get the hang of it, imagine the difference between transliterating my name to “Marcos” in Spanish or translating it to “Hijo de Marte” and you get the picture. “Cephas” is the transliteration of “Kefa” and “Peter” is the translation.

Now, here’s the thing: combined with the allusion to Isaiah 22, the name change amounts to a kind of pun and is packed with significance. Because the New Son of David establishing a new kingdom and he is taking the keys away from the bad servant (Caiaphas, the High Priest) and giving them to Kefa, the New High Priest who will exercise his authority to bind and loose.

Yes, the other apostles will exercise the power to bind and loose too. but clearly Peter is being given some kind of primatial authority here as well.

Anyway, that’s why those readings are brought together in the gospel readings. Though you might like to know.

For more on the senses of Scripture, see Making Senses Out of Scripture.