Christmas According to Dickens

The Real Business of Christmas, according to Charles Dickens

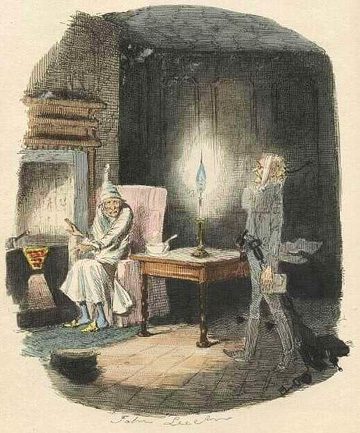

In yesterday’s post I began to explain the impact of Charles Dickens, especially through A Christmas Carol, upon our celebrations of Christmas. In fact, it’s not too much of an exaggeration to describe him, in the words of the London Sunday Telegraph, as “the man who invented Christmas.”

Dickens’ influence on our Christmas traditions is keenly felt today in many ways, even though we may not be aware of it. In this post I want to offer one salient example that flows from the pages of A Christmas Carol into our lives today.

Business in Stave One of A Christmas Carol

Early in the first stave (chapter), Ebenezer Scrooge receives an unwelcome Christmas Eve visit from his nephew. When his Uncle Scrooge questions the value of Christmas, Fred responds:

“But I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round-apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that-as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys. And therefore, uncle, though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that it has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!”

Even apart from its religious significance, Fred sees Christmas as worthwhile because it is a time of unusual generosity. Of course Scrooge doesn’t buy into this one bit. He dismisses Fred with a series of rude “Good afternoons.”

No sooner had Fred left his uncle alone than “two portly gentlemen, pleasant to behold” drop in on Mr. Scrooge. One explains his business thus:

“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the Poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

When Scrooge is unmoved, the man explains, “We choose this time, because it is a time, of all others, when Want is keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices.” Of course, Scrooge wants nothing to do with their efforts to make provision for the poor, exclaiming: “It’s not my business. . . . It’s enough for a man to understand his own business, and not to interfere with other people’s.”

But some ghostly interference in Scrooge’s life changes his opinion on the matter of his business, especially at Christmastime. The ghost of Jacob Marley, Scrooge’s former business partner, laments his failure to have lived his life well by caring for others. Scrooge attempts to reassure him by saying, “But you were always a good man of business,” to which the ghost responds:

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

Then Marley’s ghost adds an extra note about Christmas:

“At this time of the rolling year,” the spectre said, “I suffer most. Why did I walk through crowds of fellow-beings with my eyes turned down, and never raise them to that blessed Star which led the Wise Men to a poor abode? Were there no poor homes to which its light would have conducted me?”

Notice that if Jacob Marley had imitated the Wise Men, he wouldn’t have been led to worship the Christ child, but rather to be generous to the poor. Benevolence, rather than faith, is central to Dickens’s vision of the Christmas.

Business in Stave Five of A Christmas Carol

As Scrooge is visited by Marley and his coterie of ghosts, Scrooge’s heart softens towards all people, especially the poor. Thus, when his transformation is complete in Stave 5, the very first thing Scrooge does is to purchase a giant turkey for the family of his poor clerk, Bob Cratchit. Then, as he is walking about on Christmas morning, he runs into the same portly gentlemen who had the unfortunate experience of meeting Scrooge the previous day. Yet, now, things are quite different. Scrooge approaches them, offers them Christmas greetings, and then whispers something in the ear of one of the men, presumably revealing how much he will contribute to their effort to help the poor. Here’s the following dialogue:

“Lord bless me!” cried the gentleman, as if his breath were taken away. “My dear Mr. Scrooge, are you serious?”

“If you please,” said Scrooge. “Not a farthing less. A great many back-payments are included in it, I assure you. Will you do me that favour?”

“My dear sir,” said the other, shaking hands with him. “I don’t know what to say to such munificence-”

“Don’t say anything please,” retorted Scrooge. “Come and see me. Will you come and see me?”

The primary and most obvious proof of Scrooge’s transformation in the end of A Christmas Carol is not simply his delight in Christmas, nor his attendance at church, nor even his joining his nephew’s Christmas party. Rather, the proof that Scrooge is a changed man is seen in his exceptional generosity, both with the Cratchit family in particular and with all needy people in general.

So when Dickens concludes that Scrooge “knew how to keep Christmas well,” he means more than that he abolished “Bah! Humbug!” in favor of “Merry Christmas!” Ebenezer Scrooge kept Christmas well by becoming “as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.” This goodness is seen especially in his generosity, both at Christmas and throughout the year. He learned the truth that had eluded Jacob Marley in this life, namely: “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business.” These became the business of Ebenezer Scrooge, even as they should be central to the business of Christmas.

A Further Reflection

Before I stop, I would at least like to mention an obvious tension between the vision of Dickens and that of contemporary American culture. For us, Christmas is a time of business, the business of buying and selling. We hear again and again how important the Christmas season is for business. News stories about shopping abound: Black Friday, Cyber Monday, crowds in the malls, comparisons between this year and last year, predictions by economists, etc. etc. If we are going to celebrate Christmas in the secular mode of Dickens, don’t you think we’d all be better off by focusing on what Dickens considered the real business of Christmas, the business of caring for those in need, the business of giving to others, the business of generous living?

A Way to Do the “Real Business” of Christmas

![]() You may very well have a favorite charity you support at Christmastime, or you may want to give a special gift to your church. That’s great. But if you are looking for a way to share in the “real business” of Christmas, may I recommend World Vision. Their website makes it very easy for your to give a wide variety of amounts for a wide variety of causes. Personally, I choose to support the “Maximum Impact Fund.” But there are many other options. In just a couple of minutes, you could do the business of Christmas.

You may very well have a favorite charity you support at Christmastime, or you may want to give a special gift to your church. That’s great. But if you are looking for a way to share in the “real business” of Christmas, may I recommend World Vision. Their website makes it very easy for your to give a wide variety of amounts for a wide variety of causes. Personally, I choose to support the “Maximum Impact Fund.” But there are many other options. In just a couple of minutes, you could do the business of Christmas.