Naomi Shihab Nye’s poem “Kindness” speaks of how loss and sorrow are prerequisites to the “tender gravity of kindness”—how kindness comes from empathy with and identification with those who suffer. When you have woken up with sorrow, she writes, when you see how the Indian lying dead by the side of the road could have been you, you can begin to recognize that “it is only kindness that makes sense any more . . . .”

What the poem teaches is that kindness is an attitude and practice that grows from the inside out. We can try to teach children to be kind; we can certainly teach them to be courteous. But all we can really do is to plant the seeds of kindness and nurture them until life offers them its own strenuous lessons that crack those seeds open and release the green shoots.

At its root the word kind is related to kin. Kindness treats others as kindred—family folk who have a right to our consideration because we are naturally related, of one species. Our needs are the same. Our well-being is dependent in the same way on mutual care. Kindness as what we owe our kin is a tribal idea, but extends the tribe to include all who cross our paths. The mere fact of encounter with another human being becomes an invitation and a summoning to awareness: “Oh! You are here too, making your journey on this planet as I am, suffering loss, hoping for help, needing love.”

One still occasionally sees the bumper sticker that urges us all to “Practice random acts of kindness.” One widespread local response to that invitation happened when drivers at the Oakland Bay Bridge toll booth began to pay tolls for the drivers immediately behind them. As the notion of “random acts of kindness” gained traction an editor at Conari Press threw a party at which she invited all who attended to tell or write (computers were stationed around the room for the purpose) stories about random acts of kindness in their lives. I was among those honored with an invitation, and I remember it as one of the most remarkable parties I’ve been to. The book that emerged from it (Entitled Random Acts of Kindness) is worth reading as an antidote to the steady stream of bad news we’ve come to expect. Everyone there was celebrating—even reveling in—amazing graces given and received, from small gifts of parking meter money to what seemed angelic appearances in life-threatening monents. That evening kindness came to seem not just a matter of small charitable acts, but a powerful and transcendent force, very like what Dylan Thomas called “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.”

In Rick Riordan’s The Battle of the Labyrinth an older man reminds a younger, “But remember, boy, that a kind act can sometimes be as powerful as a sword.” It may be the antidote we most need to the militarism that is wreaking so much destruction. An act of kindness might be what brings us to the tipping point of consciousness that enables us to lay our weapons down and recognize each other as kindred.

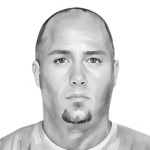

Image: Rembrandt’s Face of Christ, Gemälde Galerieen, Berlin; posted on Wikipedia.com.