THE NATURE OF THE INQUIRY

October 24, 1906.

On October 19 and October 21, just before these talks, Dewey dined with Montague. On October 23 Dewey went to Englewood, New Jersey, (presumably accompanying Montague to Upton Sinclair’s new Helicon Home Colony.) On October 20, 1906, Percy Grant was called to Brookline, Massachusetts, by the sudden death of his father, Stephen M. Grant, a prominent merchant of Boston. He remained there until after the funeral on October 22. This first Talk likely occurred on October 24, 1906.

⸻

“As I think you all know,” began Mitchell, “the inquiry which we are about to inaugurate has its immediate origin in some conversations I had with our friend, Robinson. Each of us had been interested during the summer in studying the problems of the relation of Church and State, now such a vital question in Protestant England no less than in Catholic France, and from comparing views on these matters, we were led to a discussion of religion itself and the present conditions surrounding religious thought. It seemed to us that these contrasted very favorably with those of former years; that the dogmatism of theology and the reaction from it in the materialism of science were alike breaking down; and that with the emancipation of the intellect from these two opposing limitations had come both the recognition of religion as a fact worthy of most earnest study, and also the possibility of a new view of religion itself. The new view thus made possible seemed to us characterized by directness, simplicity, and the scientific spirit—the single search for truth and its frank expression as each sees it.

Exterior of “The Benedick” 80 Washington Square East c. 1899.

“Yet the complexity of the emotions which fringe religious phenomena, the infinite variety of coloring given to religious perception by the mind and character of those who experience it, make it by no means easy to arrive at a clear intellectual concept of the religious principle, or of religion itself as a universal rather than a personal fact. There is too much that is personal which must be eliminated, too much that is only fragmentary in ourselves which must be compared with the fragments in others and synthesized into a whole, to make such an inquiry promising to a man working alone. Therefore, it seemed to Robinson and myself that it would be of both interest and value to get together a number of men from the scientific, philosophic, and ecclesiastic worlds, and see if in such a meeting of many opinions truer and broader concepts might not be arrived at than we could compass alone. Of this attempt I am the more hopeful because I believe that even where such discussions admit of no single synthetic statement, co-ordinating all the views expressed, there is yet always a certain subconscious synthesis, and that the truth is pointed by these varying expressions as the spokes of a wheel point to the nave.

“The object of discussion is thus Religion not religions. This distinction is important, for though a knowledge of Religion may be sought through a study of religions, the former is a fundamental tendency or principle, while the latter are for the most part formal systems of thought and life. The consideration of a definite religious system leads to the analysis of its particular claims, the personality of its founder, the local conditions of its origin; the mistakes of its promulgators, its priests, and external policy as an institution, its effect upon history and civilization. These concern our problem and may well receive attention, but they are not the problem itself. And indeed they seem to me to tend more to the older view of religion from which I desire to escape than to the new which I believe men generally are now beginning to take. For from such study we are led to look upon a religion as something imposed upon us from without, and exterior to our own hearts and natures.

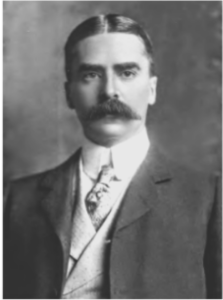

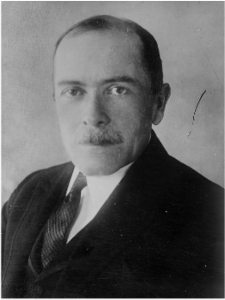

Henry Bedinger Mitchell. (Photo courtesy of Columbia University Archives.)

“Religion itself, however, the religious spirit or religious aspiration, is the most intimately inherent emotion and fact of human life. It appears in many forms and in varying degrees of development, but there is no people of whom we have any record—no race or tribe, however primitive—wholly without it. It is not only the most inherent but the most universal of human characteristics. Therefore it is primarily as a psychological or anthropological phenomenon, as an ever present and fundamental fact and factor in human life, that we seek to consider the subject of religion.

“Man is not set over against the universe but is included in it. Thus religion as a fundamental fact of human life is of necessity a cosmic fact and factor, of moment whether great or less. As religion is intimately personal on the one hand it is cosmic on the other, and religious feeling or perception seems invariably accompanied by the sense that these facts are cosmic and universal, and that in touching them our own limitations are transcended into unison with their infinitude. Has this feeling justification, and if so, can its justification be revealed? To these questions science has as yet given but little attention, and now offers no reply; the answer of the religious teacher has always been, ‘Yes, but by experience not argument.’

“In a former conversation with Robinson, he accused me of over-intellectualizing religious emotion and aspiration. Such is by no means my desire, and in proposing an intellectual discussion of the fundamentals of religion I am keenly aware of the difficulties that confront us. Indeed it is probable that I view the functions and power of the intellect in such matters as more strictly limited than would meet with your general assent. For it seems to me that the philosophic attempt to reconcile all differences and seek a fundamental intellectual unity, presupposes a highly doubtful scheme of the universe and of man’s constitution—namely, that the intellect is the all inclusive perceptive faculty. An all inclusive perception must reconcile all differences, but it may be that religious perception transcends the plane of the intellect and that the contradictions we discover in our mental views are unified not in intellectual but in religious perception and experience. This seems the more likely in that religious teaching is full of paradox, full of those Janus-faced words which mean one thing to those whom William James has called the ‘twice born,’ another to the man in the street. And, moreover, these Janus faced words are given to us as typical of life itself, and of the transformation religion makes therein.

“But whether I tend to over emphasize or belittle the intellectual element in religion, I certainly hold that religious phenomena present a wide field for intellectual inquiry, and that such discussions as I trust these will be can greatly clarify our ideas on many points. Among others I would suggest the following as part of the ground I would like to see covered:

1. “The analysis and separation of the many complex elements which are indiscriminately called religious and which are presented by and enter into religious phenomena. As an illustration of what I mean I may cite the matter in James’s Varieties of Religious Experience and in particular the descriptions of conversions. The excess of emotion there, so frequently in evidence certainly fringes the religious experience, but is it an inherent element of that experience? Is it more than the reaction upon the personality of a new and profoundly impressive insight? And does not religious feeling more often still [rather] than excite the emotional nature? In brief, what is the relation of emotion to religion? And what the relation of those other human elements through which religious feeling seeks expression?

2. “Through the study and comparison of religions and religious teachings a common part or basis may be revealed—the highest common factor of them all—and this may perhaps justly be taken as the basis of the religious life. The sifting of this from extraneous elements of custom and dogma should be of the utmost value.

3. “By an examination of primitive myths and superstitions an insight may be sought into the way in which the religious sentiment, or in lower orders perhaps more commonly the emotions of fear and wonder, are given mental form and imagery, and thus, in their simplest aspect, we may inquire into those tendencies in the mind which lead to all religious formalization and dogma.

4. “The tracing of the action of these formalizing tendencies through the evolution and growth of different religious systems,—most easily studied perhaps in the development of the Christian Church, and the effect it has had upon our civilization.

5. “From my own consideration of these questions I am led to the opinion that the answers to the first two will show the tendency of religious perception to cause us to look for joy and rest as well as for support and strength to an inner world, describable variously as of ideals and principles or of cosmic law; felt, though intangible, to be more real and permanent than the outer world around us. And on the other hand, the second two reveal with equal clearness the tendency of the personality and the effect of fear to cause us to desire a more visible support (the feeling of security given by the dollar in your pocket), and that this tendency is largely instrumental in building up the institutional church. Between these two opposing tendencies it seems to me the drama of religion finds its setting.

“There are those here tonight who are eminently qualified to deal each with some one or other of these various aspects. We might go around the circle of those present, and find in the life-work of each some special point of view we can in turn adopt and try to coordinate and synthesize with all the others.

“But above all I am desirous that the results of our inquiry should not be prejudiced in advance. As representatives of our professions we perhaps would speak in one way—as individuals, though having this professional knowledge, we may well speak in another. It is this last that is alone of value. For we are seeking to get behind the conventional forms and mental imagery of religious views to religion itself. And part of the value of such a meeting of many different lines of thought is that it will help us to eliminate from the result the special coloring of any one. Therefore I trust we may speak personally as well as impersonally; remembering that new light may lie not only in an analysis of the psychology of religious expression, but also in a synthesis of religious feeling.

“I think this should make clear what I hope these meetings will accomplish, and that I have now done my part. Certainly I have talked enough. Perhaps Robinson will tell us if I misrepresented him in what I said at first, and further suggest some line of discussion with which to begin.”

“I think Henry has given about the gist of our original conversation,” said Robinson. “There is so much indefiniteness in talk on religious subjects that it is pretty hard to know what anybody else means by what they say, even if you do occasionally know what you mean yourself. It is this indefiniteness which I would like to see attacked. Nearly anything would do to start with—you could hardly miss it from any point,—but perhaps we could begin by seeing how far apart we are on the main subject of the nature of religion by each trying to define it. That ought to be interesting—and varied. As author of the suggestion I suppose I can hardly refuse, yet it is just because I have not myself any satisfactory definition that I proposed we all consider it.

“Religion seems to be a sort of feeling or emotion which some men possess and which others do not. It appears very unequally distributed among us, and I imagine myself to be about as barren of it as most people—”

Robinson paused to acknowledge a late-arriving participant, John Dewey, who acknowledged the party with a silent nod, and found a vacant seat.

“I wish, Dewey, you had come earlier or later. Five minutes later would have done. But now you find me in the happy position of giving an explanation of what I have just said,” Robinson said with a smile. “I have neither experience nor knowledge. If you ask why I was selected to begin, I must refer you to these other gentlemen.”

The party encouraged Robinson to continue by reminding him of the silence that would fall upon history if it were only compelled to explain what it knew.

“Religion,” Robinson continued, “appears to me an un-rational emotion, more akin to the aesthetic sense than to any other. It is a going out of the emotional nature similar to that which is produced by the appreciation of a beautiful vase. Some men can appreciate beauty and some cannot. It is largely a matter of temperament. And it is as irrational or rather as un-rational as falling in love. No one can tell you why he fell in love. He may think he can, but you know perfectly well it was not a reasoned process at all. The emotional side of his nature dominated his reason, and the origin of his state and actions is in this going out of his emotions and not in the least in his intellect. An intellectual religion is a phrase one occasionally hears, and it seems to me to be just as sensible as an intellectual falling in love.

“Those whose temperaments cause such a going out of the emotional nature in religious matters find a satisfaction and a value in it which is to them its justification. It also is un-rational. In fact, most of life is un-rational. We like to call ourselves rational beings, and I suppose once in a while we are. But really it is very infrequent. Most of the time we are acting from some motive which is quite unreasoned, if not entirely illogical, and, taking men generally, not one per cent of their pleasures and satisfactions are intellectual. As I said, I do not know what the satisfaction of religious feeling is, but those who ‘have religion’ seem to find it real enough, and that it gives values which justify themselves.

“I think that is about my view of religious feeling. James’s book—The Varieties of Religious Experience—to which Henry alluded, interested me greatly, for it seemed to me to present the facts more clearly than anything I have seen, and to put them on the psychological basis where I think they belong. The records there given are full of this un-rational emotional element, this unreasoned satisfaction and sense of value. How close these religious emotions are to the aesthetic appreciation of beauty, to love and to charity, on the one side, or to sensuality, cruelty, and hatred on the other, is a further question upon which the history of Christianity and of Europe might profitably be consulted.”

Frederick Woodbridge, next in order, was asked for his views. He began by referencing the many definitions of religion which were proposed in the past—which, as it turned out, were also the subject of much philosophic argument and debate. Woodbridge had once favored the definition of religion as “the giving of cosmic significance to human emotions,” but he now believed that the term was limiting.

“The mere repetition of such definitions as these,” Woodbridge said, “and their discussion from a purely logical point of view, would contribute little towards the purposes of the present meeting. When one begins to look about him and reflect upon the life in which he finds himself, he sees first a world of mechanism, a world of physical forces and phenomena, in which, and upon which, he must act—and which react upon him. His education, his training, his whole experience, have made him familiar with this world; indeed, his existence itself depends upon his at least partial mastery of and obedience to the laws of the mechanism of life. He sees himself in a great net of mechanism, binding him not only to physical nature but to his fellows; a mechanism operative in moral and social life as in purely animal or physical life. So his first view of the world is that of a mechanical world, of facts and forces, all bound together, all acting and reacting one upon the other, and of which he is a part.

“But as he reflects further,” Woodbridge continued, “particularly as he pays heed to his own emotions and feelings, the facts of his own consciousness, he realizes that this is not only a world of mechanism but also a world of values. He finds some things valuable to him and others not, and this seemingly quite apart from the effect of these things upon the external mechanism of life,—or better, perhaps, valuable to him without conscious reference to the mechanism of life. He finds himself not only in a factual world, but in a sentient world—a world of meanings, of purposes, of ideals; of feelings and emotions, and values. These feelings and sense of values may, when viewed externally, appear to originate in and be purely personal to the man himself. But when and as experienced, intimately personal as they are, they are something more than personal. They bring with them a sense of universal, of cosmic significance and import. The search for the explanation and support of this cosmic significance of human emotions and values seems to me the basis of religion.

“In my view, therefore, religion is concerned with the world of values in contradistinction to the world of mechanism. It coordinates or seeks to co-ordinate all the non-mechanical sentient side of man’s life, his emotions and aspirations and ideals, with a cosmic life or world of the same elements and nature. In this coordination the man seeks both support and explanation of himself. There is one other thing in regard to the relation of this religious world of values to the mechanical world which seems to me significant and characteristic—and that is the sense of the pre-eminence of the former—the feeling that between these two worlds there is a causal relation and that mastery of the world of values gives mastery of the world of mechanism. It is an unreasoned feeling, but it seems both genuine and widespread.”

“The views of Woodbridge and Robinson are not contradictory,” said Mitchell, “rather, each enriches and supplements the other.”

Henry Crampton, next took up the subject.

“It may seem strange for a scientist to hold the views I do,” said Crampton, “or indeed to state any views at all upon such a question, but—”

“But, after all, Crampton, despite your being a scientist, you are a man like the rest of us,” interrupted Mitchell, “and religion must concern the man whether it touches the scientist or not.”

“Quite so,” agreed Crampton, “as I was about to say, I think most of us have passed through very much the same general experience regarding religious matters. As boys we were taught the elements of Christianity. We were brought up in one or another of the Christian sects; were told of God and of heaven and of hell, and generally given the idea that this was religion and the basis of morality. I think most of us accepted this as we accepted other things told us, or that we learned in childhood without reasoning or thinking about it at all, and that though it lay there in our minds as we matured, we paid small attention to it, finding it really touched our lives but little. We took our place in the world of men and facts around us, and our work and duties absorbed us more and more till this early religious training was quite overlaid. To the extent that we later thought of it we found it primitive and unsatisfactory. It was neither the basis of our own lives nor of the lives of those we met. Our code was not this code, our ethics not founded on any such system of future rewards and punishments. These things might be—but we, and others, acted as though they were not. Our lives were simpler, more direct and material. Certain things we felt right and did, certain other things wrong and tried to avoid. If we questioned the origin of these feelings there seemed to be a more immediate rational explanation of them than that they were taught two thousand years ago, or that the one way led to hell and the other to heaven. In short, we had outgrown the forms of our childhood, and religion and conduct were for us divorced.

“But while we were outgrowing certain forms,” Crampton continued, “we were growing into certain perceptions and feelings. We were studying nature or life itself, and the immensity and grandeur of what is were laying their hold upon us. The immeasurable lapse of time, the infinitude of space, the mighty rush and swirl of cosmic energy, the infinite richness and variety of nature, the myriad forms of organic life, and, perhaps more than all else, the slow, sure march of evolution and the immobility of law, were opening our consciousness to new perceptions and emotions. It is these emotions which typify for me today religious feeling, as I think they do for many other scientific men, and I offer as my definition of religion what Haeckel has called ‘cosmic emotion.’”

Crampton spoke with earnestness and conviction, and when he had finished there was a moment’s pause. Mitchell, a little regretful of his somewhat flippant interruption of the Crampton’s introduction, thanked him for his contribution, and his neighbor, Charles Johnston, took up the talk. Johnston was a graduate of the Bengal Civil Service, and had not only spent much time in India, but had continued a profound study of Eastern literatures and religions. It was expected that what he would say would reflect the mysticism and coloring of the Upanishads. However, he chose at first to draw from the more generally familiar sources of Tolstoy and Plato a view of religion which should include action and the will as well as emotion.

“Crampton’s quotation from Haeckel,” said Johnston, “recalls a definition of religion which Tolstoy has offered: ‘The relation which a man believes himself to hold to the universe, and to its source, is his religion,’ and he adds that in this sense everyone has a religion, as every one believes himself to hold some relation to the universe. Tolstoy recognizes three such attitudes toward the universe. What he calls the ‘savage’ attitude (not necessarily that of any race we call savage),—where a man is fighting against the universe, for his own hand; the attitude of the single contestant. What he calls the ‘pagan’ attitude,—where a man lives for a certain group or tribe or society, or even for the whole of humanity, and is willing to subordinate his personal weal, his personal views, to the weal of such a society. What he calls the ‘Christian attitude’—taking the text ‘My meat is to do the will of Him that sent me’ as a keynote, he enlarges on the attitude of one who believes he is in the world ‘to do the will of Him that sent him,’ and gives himself up to obedience to this will.

“This comes close to my own idea of religion,” said Johnston. “Just as our muscular forces come in relation with the universal force of gravitation, and all our physical life is thereby possible, so I believe our spiritual forces are in relation with a universal divine will, which we touch inwardly and directly through our own wills; and in obedience to this will lies our possibility of spiritual well-being and growth. As Dante says: ‘In His will is our peace.’

“Therefore, religion seems to me a matter of the will; a putting our wills into relation with the divine will, and an obedience thereto. Compare Plato, who in the Apology makes Socrates say that he had always been conscious of a god-like voice within him, stopping him if he were about to do anything not rightly; or compare the Katha Upanishad: ‘The dearer is one thing, the better is another. These two draw a man in opposite ways. It is well for him who follows the better. He fails of his goal who follows the dearer.’ So I think religion is the will in action—the free and determinative choice between the better and the dearer, between what is felt to be right and what is felt to be pleasant.”

“I take it, then, that you are adding, to the definitions previously given, the ethical element,” said Mitchell.

Upon this, it was as though a stone had been thrown into a hornet’s nest. There was an immediate buzz of query and protestation. Religion was one thing, ethics another. Yet was it after all so certain that they were separate? True, there are many possible bases for ethics, many a moral man would call himself without religion, yet was not perhaps ethics itself that man’s religion? Again, was, or was not, religion always accompanied by a system of ethics? Johnston had spoken of the action of the will, the choice between good and bad as constituting the greater and more vital part of life. Surely this was not actually the case. Such deliberate choice was rare. Most of our actions were determined by habit. But this habit must have had its origin in such choice. To appeal to habit was but to push the determinative action of the will into the past, not to remove either it or its paramount importance. So argument pressed on argument from around the circle. It was evident these men had won their intellectual liberty too hardly to suffer even the suggestion that religion and morals were bound together. The word “religion” when used by another still carried the implication of religious forms and dogmas, and the unprovable but oft quoted theological corollary that an attack upon religious dogmas was an attack upon morality still lingered in their minds.

Finally, Johnston succeeded in making it clear that no such connotation was intended and no such actual meaning existed in what he had said, but nevertheless an emotion or feeling which did not touch the will, could not, in his judgment, properly be given as a definition of religion. The essence of a man’s religion was shown through his will, neither through his mind nor his emotions.

“I do not know whether it is because I am unaccustomed to just this sort of discussion,” said Grant, “having been for so long outside the academic atmosphere, that it seems to me we have been talking more of the philosophy of religion than of religion itself. The search for an explanation of our sense of values, the emotions we experience in contemplating nature, the determinative choice and action of the will, all appear to me as elements in the philosophy of religion.

“Religion itself I view as a relation—a relation between man and God. I use the term ‘God’ because it is the most familiar to me and the best I know. Yet it may have different connotations in the minds of others. For myself, I would be willing to accept the views of Sir Oliver Lodge, which appeared recently in the Hibbert Journal. I think with him that as we look out upon life, upon its richness and variety, and its wonderful order and law, that it is impossible for us to believe that our own consciousness and intelligence—yours and mine, just as they are—are the highest type which exists. I know for myself I cannot believe this, nor does it seem to me logical or to be believed. I am willing that my use of the term ‘God’ should be taken as the synthesis of all this range of higher intelligence—of all that is beyond and above us. If you care for a definition, how would this do?—Religion is the instinctive alliance between God and man, by which the highest image of human possibilities is revealed, and help to perfection is received.

“Religion from this point of view, as the relation of man to what is above him, is also expressive of and expresses itself through ‘the climbing instinct,’ as James Russell Lowell called it—the instinct or power which operates to raise and better us, to lift us into the likeness of something higher. And this instinct is a prime deposit in our nature.

Nor did’st Thou reck what image man might make

Of his own shadow on the flowing world;

The climbing instinct was enough for Thee.

“I find certain religious practices of great assistance in producing a higher spiritual consciousness—especially prayer. Prayer is the greatest assistance and satisfaction of my life, the deepest happiness. It not only strengthens me by giving me the feeling of a divine companionship, but it relates me to all mankind by the noblest and most powerful sense of fraternity and serviceableness.”

“I would like to ask you, Percy, whether you would exclude the relation of a dog to his master from your definition of religion as a relation,” said Farrand. “I have been very much interested in what you have said and in particular in your use of the word ‘relation.’ In writing of the earlier expressions of the religious instinct we have been much puzzled what word to use. I have been inclined to use ‘attitude’ but I think your use of the word ‘relation’ is perhaps the better, if it includes such a relationship as I have instanced.”

“Yes,” replied Grant, “I think it might, so far as that is a relationship of an inferior to a superior intelligence. But it is, of course, difficult to say what the relation of a dog to his master really is.”

“River Yukaghir family outside home, Siberia, 1897-1902.” Item#: 22233 Courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library.

“That is the trouble with pushing such an analogy,” said Farrand. “None of us knows what is actually going on in the dog’s mind and so what his attitude really is. But the simile is suggestive in some ways.”

“Has not Manitouism recently been proposed for the designation of the belief in a higher power than man himself, or for the simplest form of religious belief?” Mitchell asked.

“Manitouism,” replied Farrand, “has been suggested, but it is in fact by no means a crude or primitive form of belief. It is a very complete system. ‘Belief in spirits’ has been used to denote the early expression of religion, but very likely that also is not the beginning.”

Livingston Farrand.

“Percy defines religion as a relation,” said Dewey, “but to me that seems very indefinite. There are so many types of relation and surely not all of them are religions. Again, a relation may be entirely unconscious, and I take it that a man unconscious of his religion would not be called religious.”

“It is perhaps more the sense of this relation than the relation itself which is one’s religion,” said Crampton.

“I imagine Percy included the sense or consciousness of the relation in his use of that term,” said Henry. “Surely all men must be in some relation to God, and it would seem to be the extent to which they were conscious of this and made it a personal rather than impersonal relation that determined the nature of their religion. Am I right in this, Percy?”

“Certainly,” said Grant. “I intended to include awareness of this relationship. And its active character, from one side at least, I indicated by what I said of the climbing instinct and of prayer.”

“But I am puzzled, also, by your view of religion as a climbing instinct,” said Dewey. “Does not this contradict the most characteristic feeling of religious emotion and experience? I mean the sense of peace, of permanence, indeed of absolute inertia, neither desiring anything else nor, indeed, with any thought of anything else?”

“Is not this the temporary result which the climbing instinct has sought?” Griscom asked. “It reaches its momentary satisfaction in this peaceful state and sense of enlightenment or union with something higher. Falling from this, it starts to climb again—or, as it becomes familiar with this state, new heights open before it.”

“But even so,” replied Dewey, “this state is, properly speaking, more truly a religious condition than is the struggle which led to it. And in many cases there was no such struggle. This feeling came as an unexpected vision. Then, too, in my own case I do not find the synthesis of feeling, the unification of life and action which others speak of, as the result of religion. On the contrary, action becomes more complicated, more perplexing. With increased religious knowledge it seems more difficult to live, not simpler.”

“I had been trying earlier in the evening to formulate my own definition of religion,” said Griscom, “and I found in listening to our friend Percy that I not only agree with all he has said, but had actually used his words to express the main idea, namely, ‘Religion is the relation between man and God.’ What different persons mean by God varies greatly. Consequently their religions differ. I happen to know, for example, that my idea of God is different from Percy’s, and so what religion means to me is different from what it means to him. To go back a moment to what James said, when he spoke of the emotion, or instinct, we all possess—but in varying degree—he likened it to the aesthetic instinct, and he spoke of the emotion we felt when we gazed at a beautiful vase. He also likened it to love, which we feel for a person. But in each of these illustrations, there is an object towards which the emotion is directed. In the description of the religious instinct, however, he said nothing about its object: the thing or being toward which it is directed. I think this, however, is the essence of the question. We all acknowledge the existence of the religious instinct, but its character, the character of the religion itself, is largely determined by the character of its object. So I do not think we can arrive at a very clear idea of religion unless, in addition to an analysis of the instinct itself, we take into account the nature of the objects toward which it turns. It is the difference in these latter which seems to me really determinative.”

“Do you think, Clem, that the ultimate objects of religious feeling are themselves and in essence so different in different people?” asked Mitchell, “or do you think that these differences are in reality more an affair of words than of fact,—simply different mental expressions for the same thing? As the same light will receive different coloring coming through different glasses. In the latter case they would not seem as important as in the former.”

“They seem to me of vital importance,” said Griscom, “indeed determinative, as I said, of the whole character of a man’s religion. A man who believes in an anthropomorphic God, as did many of the saints of the Middle Ages whose lives and visions are recorded for us, has a very different religion from one whose view of the Deity is purely pantheistic: the religion of the fetish worshiper is not that of the Hindu contemplating Parabrahm. The differences, alike in men and in their religions, consist in the different nature of the objects to which they turn their desires or to which their emotions respond.”

“I think, Clem, you are in a philosophically untenable position,” said Woodbridge. “On the one hand you define religion as a relation, and on the other you say its character is determined by the object to which we are related, and that differences in this object necessitate differences in the relation. I think that is a non-sequitur. We are often in the same relation to different objects. I am the brother of two different people. The relation of love exists between a man and many different types of character and existence. It is a most common psychological fact that the true character of an object has very little to do with the emotions we may entertain toward it. In other words—though of course not all objects can be viewed as entering into all relations—the character of the object and the character of the relation are philosophically quite distinct.”

“I suppose that is so,” said Griscom, “and that my view would require restatement, if it is to avoid these pitfalls of philosophy for the trapping of the unwary. Nevertheless, I stick to my contention—that the relation which a man feels to exist between him and God and the nature or character which he ascribes to God are the two fundamental and determining elements of his religion. The first element had already been brought out by Percy. I wanted to suggest the second as equally important.”

“Percy spoke of religion as the climbing instinct,” said Calkins, “the instinct or power by which we seek to broaden and lift the individual life. That is not religion, but life itself. It is as manifest in the amoeba as in man. It is an underlying principle of evolution, a fundamental factor in all growth and life. I do not see that it is necessarily at all a conscious process, and it certainly is not confined to humanity.”

“I doubt whether it is necessary or desirable to so confine our view of religion,” said Mitchell. “Indeed, if religion is as fundamental as some of us feel it to be, it would be an almost inevitable consequence that in one way or another it ran through all life.”

Gary N. Calkins. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (1924.) ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/2861.

“That is what I think we should try and get at,” said Calkins. “Religion is not love, it is not emotion, it is not awe, it is not the choice and action of the will, but something which causes these, itself beneath them, more inherent and basic. Ordinary love, for example, is not sexual union, nor the desire for such union, but is a phenomenon which has developed from these through long periods of evolution. We can thus trace the growth and evolution of sexual attraction and of love back through these primary facts of animal life to relations between reproductive cells, and back of these again to chemical and physical properties. Can we do the same with religion? What is the basis of religious attraction? What is the natural fundamental fact or law or force underlying these religious feelings and causing them? Those are the questions which I think are the vital ones. What is back of man’s religious feeling? What its origin, its cause, its significance?”

“Can we not find such a basis for religion,” asked Mitchell, “—what is in essence a physical basis—along the lines suggested by Woodbridge when he said we lived in a world of values as well as in a world of facts? I know that is the intellectual justification I give my own religious aspiration. There is no need to assume the inner world of values, of aspirations, ideals, and moral law to be totally immaterial and without physical basis. On the contrary, I think common sense requires us to postulate a physical basis for it, and that much is gained by doing so. It may simply be a different kind of matter subject to different laws; as the ether which is the physical basis of light and electricity and magnetism is a different kind of matter from this chair. Man today is living in both worlds, partly conscious in both worlds, though his consciousness of the inner world seems very dim and blind, so that perhaps instinct and feeling better describe it than consciousness. But blind as it is, this feeling brings, as Crampton said, the sense of the greater richness and value and vitality of the inner world, the sense that in some way it is higher and better for us if we could only come to full consciousness and mastery of it.

“More than this, it seems to me as though there was a certain compulsion toward this inner life, not only the sense that we ‘ought’ to value such insight as we have gained of it and to follow our feeling of its laws, but as though, willy nilly, the tide of life was pushing us in that direction. I understand that you biologists hold the earliest form of animal life to have been aquatic. There must have been a time when it became amphibious and passed thence to living in the air—matter in quite a different form. So it seems to me of the outer world and the inner world, and that it is possible that religion can find a physical basis in the evolution of man from one to the other.”

When Mitchell finished, Farrand rose to leave, for it was now quite late. This ended the discussion, and, after arranging their meeting for the following month, the party adjourned.

⸻

Exordium: Conscientious Clergyman.

Chapter I. The Nature of the Inquiry.

Chapter II. Christianity and Nature.

Chapter III. Evolution And Ethics.

Chapter IV. Power, Worth, and Reality.

Chapter V. Pragmatism and Religion.

Chapter VI. Mysticism and Faith.

Chapter VII. The Historian’s View.

Chapter VIII.Organization and Religion.

Chapter IX. The Theosophical Movement.

Chapter X. Signs of the Times.

Chapter XI. Has the Church Failed?

Chapter XII. Silence.

⸻

CITATIONS.

Maurice, Arthur Bartlett, “New York In Fiction Pt. II: About Washington Square.” The Bookman. Vol. X, No. 2 (October, 1899): 128-143.

The Scribe. “Talks On Religion.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. IV, No. 3. (January, 1907): 227-240.

Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. Talks On Religion: A Collective Inquiry. Longmans, Green, And Co. New York, New York. (1908): 1-31.

Higgins, Shawn F. “The Benedick: An Analysis of Talks on Religion.” Dewey Studies. Vol. VI, No. 2. (2022): 16-75.