POWER, WORTH, AND REALITY.

January 23, 1907.

Days after the December talk, on December 29, 1906, Johnston delivered a lecture titled “Helping To Govern India,” at the American Political Science Association at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. In January 1907, Guy A. Tawney, a visiting professor who taught “The Principles of Science,” and Walter B Pitkin, a tutor in philosophy, resigned from the philosophy department at Columbia University. This necessitated a reorganization of the faculty positions by the board of trustees. Miller advanced to the rank of professor; Montague to that of adjunct professor; Harold Chapman Brown replaced Pitkin as tutor in philosophy; Max Eastman replaced Brown as assistant in philosophy. It was at this meeting of the board of trustees that Calkins’ title was changed from Professor of Invertebrate Zoology to Professor of Protozoology, in recognition of his “commanding position as an investigator in this field.”

Appleton Chapel.

Grant paid a visit to his alma mater, Harvard in mid-January. The study of religion at Harvard was about to enter a new era, as the Harvard Divinity School was in the preliminary stages of a proposed alliance with the nearby Andover Theological Seminary, and with it a new building on campus.

Harvard Divinity School c. 1907.

On January 20, 1907, Grant delivered a sermon“Good and Bad Impressions,” at Harvard’s Appleton Chapel, in which he said:

We are daily receiving myriads of impressions—so many that they confuse and weary us by their very number. Some are pure, others impure; some are bright, others are somber. We go to the seashore and into the country seeking the purest and noblest impressions, and behold we are greeted by flaunting signs on fences and housetops. Travel should not create a similar impression to turning the pages of a trades Journal, but the lining of our great railroad routes with unending advertising makes it amount to about the same thing. The child will inevitably draw its impressions from the corner saloon if that is the most familiar object of the landscape to him.

From the multitude of impressions we must select those that will direct us along the right path. Let us try to make the selection as God would, let us forsake no good practice merely because some of our friends have given it up in order to conform to the customs of the society in which they live. Let us not starve because another sneers at our food. Jesus illustrated this law of selection, the world did not mold him. He molded the world. Above all let us once surround ourselves with an atmosphere of religious faith and evil will rebound from it as from armor.

Irving Street, Cambridge Massachusetts.

We know that William James was among the parishioners. In a letter to his daughter dated January 20, 1907, James writes:

Sweet Peglein:

Just before tea! And your Grandam, Mar, and I going to hear the Revd. Percy Grant in the College chapel just after. We are getting to be great church-goers.’T will have to be Crothers next. He, sweet man, is staying with the Brookses. After him the Christian Science Church, and after that the deluge! I have spent all day preparing next Tuesday’s lecture, which is my last before a class in Harvard University, so help me God amen! I am almost afraid at so much freedom. Three quarters of an hour ago Aleck and I went for a walk in Somerville; warm, young moon, bare trees, clearing in the west, stars out, old-fashioned streets, not sordid—a beautiful walk. Last night to Bernard Shaw’s ex-quis-ite play of “Cæsar and Cleopatra”—exquisitely acted, too, by F. Robertson and Maxine Elliot’s sister Gert. Your Mar will have told you that, after these weeks of persistent labor, culminating in New York, I am going to take sanctuary on Saturday the 2nd of February in your arms at Bryn Mawr. I do not want, wish, or desire to “talk” to the crowd, but your mother pushing so, if you and the philosophy club also pull, I mean pull hard, “Jimmy” will try to articulate something not too technical. But it will have to be, if ever, on that Saturday night. It will also have to be very short; and the less of a “reception,” the better, after it. Your two last letters were tiptop. I never seen such growth! I go to New York to be at the Harvard Club on Monday the 28th. Kühnemann eft yesterday. A most dear man.

Your loving,

Dad.

Two days away from retirement, James had recently returned from Columbia University where he delivered the presidential address at the American Philosophical Association. With the prompting of his former pupil, Dickinson S. Miller, James agreed to return to Columbia, in late-January, to deliver eight lectures on Pragmatism. It was perhaps through a conversation between Grant and James, that Miller makes his first appearance in the January Talks. On January 23, 1907, Grant hosted a private meeting of prominent Episcopalian church members in his home to discuss what actions could be taken to support Algernon Crapsey. Griscom and Mitchell, junior-members of the vestry who were sympathetic to Crapsey, were likely in attendance. In the January 1907 issue of The Theosophical Quarterly, Griscom writes:

The whole of history is full of nothing less than disgraceful exhibitions of intolerance. Christian or Pagan, Fire-worshiper or Idolater, they are all alike. It is one of the quicksands of the religious thought of nearly all ages and of nearly all people. Even to this day, when we are wont to boast of our so-called progress and broadmindedness, the Protestant Episcopal Church in America is rocking on its foundations because of the trial and conviction of Dr. Crapsey for heresy. We no longer burn people at the stake for holding opinions which differ from our own, but we can still deprive them of their benefices and suspend them from their priestly functions.

Miller, who was vocal in his support of Crapsey, may have also been present. With Grant’s meeting taking place on January 23, 1907, it is likely that the January meeting occurred that same evening.

⸻

“It will be remembered,” said Mitchell, “that at our last meeting Crampton developed the theory that ethics and religion were, in fact, founded on biological principles, and could be viewed as evolutionary derivatives from the fundamental laws of self-preservation and the perpetuation of the species. In this view, Nature herself—whether moral or immoral—is seen as inculcating morals and religion in her children, by the simple expedient of letting those die that are without them; so that the religious principles are the principles of effectiveness in life as it is; and the religious attitude the attitude of acceptance of universal law. To this thesis Monty raised two objections: first, that self-preservation was by no means a fundamental law or tendency, and second, that the universe, as it is, is very far from acceptable. I have, therefore, asked Monty to start our talk this evening by a more detailed exposition of his views.”

“I am sorry,” said Montague, “but I did not understand that you wished me to speak to any given point, and therefore I am afraid what I had intended to say bears very indirectly upon the question which was at issue in our last meeting.”

“I did not mean to limit you at all,” said Mitchell, “and would much rather have a constructive exposition of your own opinions than a criticism of what has been already said. You remember that at our first meeting you remained silent, so we have still to hear even your definition of religion.”

“It was that which I had meant to present tonight,” said Montague, “so, if you are willing, I would ask you to consider what we may call, ‘A Definition of Religion, Based upon an Examination of the Various Forms of Religious Belief.’ We may construct a definition of a term such as religion in two ways: first, by introspective analysis of the experience to which we apply the term in our own life; secondly, by observation of the experiences and practices to which others have applied the term.

“Religion means to me something very simple—it means the emotional attitude that results from a blending of the two feelings of dependence upon a higher power than my own, and respect for a higher worth than my own. These feelings of dependence and reverence, or of fear and admiration, can only be blended in one way, namely, by being directed toward a single object in which are united the attributes of superior power and of superior worth. I can think of the object of my religious attitude as a personal God or as something very different, but so long as the object, whatever else it may be, is an identity of a deeper reality and a higher or more perfect ideal, it inspires the religious emotion.

“If I should be led to believe that the universe, or any power in the universe, on which I am primarily dependent, should lack this superior worth or value, my attitude toward that object would cease at once to be religious, even though I might deem it necessary to pray or sacrifice to it, or in other ways manifest my fear and sense of dependence. If, on the other hand, I should become convinced that my ideal of perfection was nothing more than an ideal, and was nowhere embodied or realized in the universe or in any existent power on which I depended, why then also the name ‘religion’ would cease to be applicable to my attitude toward that ideal. In short, any doubt as to the identity of power and worth of the real and the ideal is a doubt of the objective truth of religion, and destructive of that subjective religious attitude in which the feelings of reverence and dependence are always blended.

“Turning now from this definition of religion, a definition based wholly upon introspection, let us examine the various types of religion that actually exist or have existed. And here a single meaning for the term seems hard to find. In the first place, we cannot say that religion is the belief in one God, because that would bar out the polytheistic religions; nor, secondly, can we say that it is a belief in a personal God, for that would bar out the great systems of pantheism, which have at least a de facto right to be called religions; nor, thirdly, may we even define religion as a belief in Gods, one or many, personal or impersonal, for that would bar out Buddhism, which is properly an atheistic religion, and in which the ideal condition of being, called Nirvana, is the object toward which the religious attitude is directed, thus taking the place of the God or Gods of the theistic and pantheistic religions. All these definitions seem, indeed, to be too narrow; but if, on the other hand, we define religion as the ‘climbing instinct,’ as the ‘sense of aspiration,’ as the ‘recognition of the supernatural or the unknowable,’ as the ‘feeling of obligation,’ as ‘cosmic emotion,’ or as ‘sheer undifferentiated and hysterical emotion of any sort,’ we make the definition so broad as to lack the specific qualities which mark it off from the merely ethical or aesthetic attitude. And yet, if we return for a moment to the five types of religion indicated above, I think we shall see that there is one and only one fundamental characteristic common to all, which will, therefore, serve us as the meaning of the term ‘religion.’

“These religions were: first, Monotheism, the belief in one personal God; second, Polytheism, the belief in several personal Gods; third, Pantheism, the belief in an impersonal God; fourth, Fetishism, the belief in many impersonal Gods or rather forces; and fifthly, Buddhism, the belief in a supremely real and perfect state or condition of being. Now all the theistic religions attribute to the being or beings called God not only superior power, but superior virtue. Even the fetish is not, I suppose, a mere power, but possesses something that may inspire respect or admiration as well as fear. While in the case of Buddhism, Nirvana, although not an entity or God, is a mode or condition of existence that possesses the distinctly Godlike duality of aspect in being at once more real and more perfect than what we know in nature. Is it, then, too much to say that an examination of religions leads us to the same conception as that which resulted from introspection, namely, the conception of religion as a blend of the feelings of reverence and dependence directed to an object in which, whatever its particular nature may be, worth and power are blended? We may note, parenthetically, in justification of this view, that there are two distinct types of the ceremonial expressions of the religious attitude that correspond perfectly to the duality of that attitude and of its object, that is, praise and prayer. In praise we direct our attention to the ideal or value aspect of the divine, while in prayer the feeling of dependence upon a superior power is predominant.

“I suppose it is true that in the more primitive religions, as typified by Fetishism and the lower forms of ordinary Polytheism, the element of respect is overwhelmingly dominated by the sense of fear and the desire of gain. Perhaps it may be held that in some cases the objects of the religious attitude are in no sense superior, but even inferior in moral worth, to the men who worship them, and that consequently the definition that I have proposed would be inapplicable. And I should admit that many features of primitive religion would better deserve the name either of demon-worship or mere supernaturalism, and that it is very probable that religion has originated from a sort of pseudo-science or magic, in which various esoteric rites are performed with a view to controlling in that way those natural forces which men have not yet learned to understand and control by ordinary methods. What seems to me certain, however, is the fact that as religion develops from this pre-religious stage to higher and higher forms, there is a steady increase in the ethical element. The Gods become, with increasing distinctness, the depositories of tribal or racial ideals. And by this I do not mean merely that the morality ascribed to the Gods becomes more perfect as their human worshippers become more perfect, a truth which everybody will admit, but that the moral side of their nature becomes more nearly equal in importance to their physical side; the advocates of religion appeal less and less to man’s fear of supernatural powers and more and more to his reverence for superhuman worth and perfection.

“It is customary to testify to this view by pointing to the Hebrew religion as being superior, not only to the other Semitic Cults, but even to the religion of the Greeks, in that Jehovah was recognized as being primarily a God of righteousness; and this of course is true, though it is only fair to remember that the Greeks, in ascribing to their Gods a lack of enthusiasm for bourgeois standards of morality, by no means meant to imply that they were seriously lacking in aesthetic or even in ethical attributes.

“Now the highest point to which a religion could develop would be, I suppose, the belief in one infinite and omnipresent Reality, that possessed or embodied at the same time the ideal of infinite perfection. The two essential aspects of deity, that is, power and worth, would then be of quite coordinate importance, and each would be at a maximum. And if we disregard the question of the actual truth or falsity of such a belief, I suppose that most of us would agree that it is only this monotheistic type of religion that we should care for. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that the development of religion did not cease when it attained to its highest perfection—that is, the recognition of the equal importance of the ethical and metaphysical aspects of deity—but passed over on the other side, so that we now have in several quarters the curious conception of God as an ideal being, lacking, however, all objective reality.

“This view of God, or the object of religious emotion, as not of necessity real, but only ideally perfect, dates from Kant’s somewhat ambiguous system of Practical Reason. In the early nineteenth century, the French philosopher, Vacherot, explicitly states that perfection and existence are incompatible, and that religion must content itself with a God that is unreal. Professor Santayana, of Harvard, who is at present the chief exponent of this view, goes further and maintains that it is not only a necessity, but a positive benefit for religion to divorce itself from ontology altogether. Just as our appreciation of the character of Hamlet is hampered by an irrelevant curiosity as to whether any such person really existed, so, Santayana tells us, religion is vulgarized and destroyed by demanding that its ideals be embodied in the realm of existence. This sharp severance of the ideal from the real, and the consequent banishment of the objects of reverence from the world of actualities, seem to me to characterize the religious attitude of a steadily growing class of thoughtful men and women. And for this reason I believe Santayana’s writings upon religion deserve a more critical consideration than they are at present generally receiving.”

“Note that this final stage of religion is in exact logical antithesis to its first stage,” said Montague. “In the first stage the gods exist as powers, but they are lacking in worth—religion is identified with propitiatory rites or magic. In the last stage the gods possess perfection and ideal significance, but lack existence. Religion is identified with poetry. And between the magic from which religion springs and the poetry and symbolism in which it has here culminated, there is room for all the stages that may be found in its development. Both of these extremes are equally far from the ideal craved by the religious consciousness. For mere reverence for ideals without an accompanying feeling of dependence upon a power not ourselves, in which they are embodied, is as truly irreligious as is the feeling of dependence on supernatural powers which lack moral worth. But these two forms of irreligion seem to me to mark out quite perfectly, as I have said, the opposite limits between which all religions may and must be placed. And it is because they illustrate and approximately verify the conception of religion embodied in my definition, as well as for the intrinsic significance I believe them to possess, that I have spoken of them here.”

“As I understand your thesis,” said Mitchell, “you begin by defining religion as a sense of dependence and reverence upon that which has power and worth. You substantiate this, first by introspection and then by an examination of known religions. In the historical sequence of these latter you find an evolution through three broad divisions. In the first, exemplified by Fetishism, the aspect of power is predominant and the aspect of worth is negligible. In the second, exemplified by Monism, the two aspects have become equal in the concept of an omnipotent power of infinite worth. In the third, put forward by Santayana and certain modern idealists, you find the aspect of worth still perfect, but the aspect of power non-existent—as the object of reverence has become purely an ideal, toward which you cannot feel a sense of dependence. The result of this evolution of religion is that you feel all that is best in you to be severed from the universe at large and your own life to be left without support precisely where you most desire it.

“Now in this the crux of the matter is the denial of reality to the ideal.

“I have never been able to appreciate the philosophic anxiety as to the reality of a given object. Everything that is is real. A reflection is a real reflection, a lie is a real lie, any concept a real concept. The trouble arises when we try to classify our perfectly real concepts, and in particular when we try to ascribe physical existence to that whose existence is not physical. I confess it seems to me as though much thought was very loose in this matter, and as though there was a tendency to confuse physical existence with reality, or at least to view the former as a necessary attribute of the latter, while in fact it is no such thing. I do not question the reality of my keys because they are not in the pocket where I first searched for them. Neither should I question the reality of any object because I find it in the realm of the heart and the mind rather than of the body. If one is to discuss reality at all, one must adopt some other criterion than the department of life in which a thing is found. It seems to me that the most useful test is that of effectiveness—the pragmatic test, if you like: what does this object effect? what difference does it make? If it has any effect, or makes any difference, then it is certainly real.

“Judged by this, or, it seems to me, by any other test, our ideals are both real and effective,—the most dynamic of all forces. Ideals are not static pictures which we gaze upon unmoved; but powers which possess us, compel our acts, and mould our lives. Honor, Loyalty, Patriotism, these are ideals, yet what is more real, what more dynamic, more compelling? What stronger incentive have we than our ideals? What is there for which men lay down their lives so readily, or which has made such history? Surely patriotism is more effective as a spur, more sure as a support, than dollars or whips or any material agency could ever be.”

“Ideals are real as ideals,” said Montague, “but only as ideals. We crave something more than this, and would see them embodied in the external universe. A man thirsting in the desert would have the ideal of water, which would certainly be real as an ideal, and which would be effective in shaping his action. But what he wants is water—real water which can assuage his thirst.”

“You make there several points,” said Mitchell, “all of which show themselves, to my mind, with a little different coloring. I hardly think we can regard our ideals as made by ourselves, but rather as chosen by ourselves—a selection from powers already in life and in the universe, which we choose to light and guide our personal existence, and by so doing we augment what we have chosen. It would seem to me that the inner world, of ideals and aspirations and religious feeling, existed as independently of our personalities as does the outer physical world—the difference between them being one of dimensionality, so that in the physical world a thing is either in or without our bodies, but in the spiritual world it is both in and without at the same time. We live in an atmosphere of ideals as truly as in an atmosphere of air. Each is impalpable and invisible, yet each supports and nourishes, the one the inner man and the other the outer. Only in the former there is a greater selective action of what we shall take and what we shall reject, and we grow into the likeness of what we take.

“You have contrasted the ideal of water with the reality which the thirsty man craves. In this case the craving is for physical nourishment, and physical reality is demanded of that which would fulfill it. But the religious craving is for spiritual nourishment, and spiritual reality is what is demanded in its object. There it is that the ideals we hold to can support and strengthen us. Strengthening the spirit they strengthen the whole man, leading him through pain and privation and hardship, under which he would otherwise sink. This is not some idealistic theory, but a fact to which the history of every great struggle bears witness. It therefore seems to me but a half truth to view ideals as a craving, and not recognize that they are also the fulfillment of that craving.

“Again, you demand the embodiment in the external universe of the object of religious feeling. In one way I do so also, in that I believe there is the hunger in every man’s heart to embody and express the ideal he loves, or the Will of the Father to whom he turns; to express it and to make it, through himself, a living power in the physical world as it is in the spiritual world. To the extent to which they have been embodied in the great teachers of the race, ideals have been objective physical realities—but beyond that it seems to me unreasonable to go. Why should we demand of an ideal the same type of reality and existence as that of a stone wall?”

“It may be unreasonable,” said Montague, “but I am quite sure it is the fact that we crave other types of reality in the object of religious feeling—the stone wall reality, as well as the reality of our ideals. And when either of these types of reality is absent or obscured, then our religious faith suffers. Take Huxley as an illustration, and recall what he said as to the loss of religion through an acquaintance with science, which shows us nature as immoral. Remember his statement that there could be no such thing as a ‘natural religion’ and that there was nothing in nature which jibed with our own ideals. Huxley lost his religion as soon as he felt that the world of space, and time showed no power making for righteousness, or gave no echo back of his own ideals. He did not, therefore, abandon his ideals. On the contrary, he held to them the more firmly, and felt it the more incumbent upon him to champion them with all his strength. But he ceased to be religious.”

“Huxley claimed to have lost what he all the time had in his breast pocket,” said Miller. “I say advisedly his breast pocket.”

“I think the objects of religion actually possess both types of reality,” said Johnston, “and that the deeper we look into life, the more convinced we are of this. It seems to me that it is a very one-sided science which sees nature as immoral,—one-sided, short-sighted, and illogical. Indeed, is not the man holding Santayana’s view in the position of one moved by patriotism, after deciding that he has no country?”

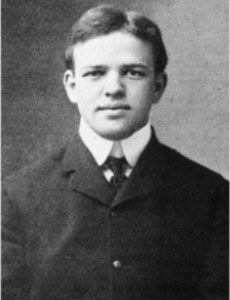

Harold Chapman Brown.

“It is just that sense of having a country,” said Brown, “of being part of a larger whole—that seems to me the essence of religion, in contradistinction to morality.”

“I know that it is the fashion nowadays for you philosophers to insist upon a divorce between ethics and religion,” said Griscom, “and you are all up in arms at once when the two are considered identical—or coterminous. Yet I wish you would explain to me how you ever would have known anything of ethics or morals except through religion. There never would have been any such things. The human race must have had some idea of God before ethics, which are the laws governing one’s relations to God, and the way one must act to reach God, could ever have been established. Once in existence as a part of the world’s heritage of ideals, it seems to me you seize upon them and coldly show the door to religion which gave them birth.”

“I understood that Crampton took up that point at your last meeting, and endeavored to show that religion was a later development than ethics,” said Brown, “the latter being directly founded in biology. But is it not also true that we find all sorts of moral ideas associated with different religions? And that this diversity is so wide that it is almost necessary to conclude that religion has nothing to do with morality?”

“I think Clem’s point is not that religion precedes ethics,” said Mitchell, “but that the two are, in reality, always tied together. Religion, let us say, as a sense of a relation between man and what is beyond him, ethics as the working out, or expression of that relation in his life and acts. This in no way contradicts Crampton’s view of ethics as biological efficiency, if we think of the end of the evolutionary process as union with God. But it shows us, what I think was Clem’s mind, that it may be quite misleading to divorce, in thought, what in experience are so closely united.”

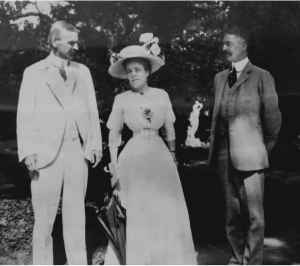

(Left) C.A. Griscom, Jr. (Center) Genevieve Ludlow Griscom. (Right) Henry Bedinger Mitchell.

(Photo courtesy of the Griscom family)

“That was exactly my point,” said Griscom, “but I did not mean to divert the conversation and would like to return. I understood you to say, Monty, that the evolution of religion has followed the line of development you so clearly described, with the result that we have reached the impasse set forth by Santayana. Do you mean that the main current of religious evolution has, in your judgment, itself reached this hopeless point, or do you think Santayana represents merely an offshoot,—an eddy, leading to some stagnant backwater?”

“I would like to believe the latter,” said Montague. “Upon the surface of things, with such knowledge as I now possess, I am forced to give partial assent to Santayana’s view, in that I do not see any other support for my aspirations than that which my ideals themselves furnish. But I am always hoping to come to some deeper insight; that the development of science, or the later evolution of religious thought, will bring to the surface some hitherto unnoticed facts; will put the whole external universe in some new and more moral light; and that the reality and power our hearts crave will be restored to the objects of our worship.”

“Monty, if you will pardon a personal question,” asked Clem. “I should like, very much, to know whether you do not really have two theories about religion; one, a very interesting hypothesis, which you put forth for argumentative purposes when discussing these things with your friends; and another very different theory, which is the working hypothesis upon which you base your conduct and your life. I suspect we would not differ very much from this ‘private view,’ which seems to shine out almost unconsciously from much that you say.”

“No, I hardly think I am guilty of that charge,” replied Montague, “though, probably, I have a vague faith that things are better than they appear on the surface to be.”

“It seems to me there is a fundamental fallacy in the thought that religions evolve,” said Johnston “It is quite true that we see in the world the three broad divisions of religious feeling which Monty has described, but nowhere do we see the evolution of a religion from a lower to a higher form; as, for example, we can trace the evolution of biological organisms. Is it not now generally recognized that the doctrine of evolution has been too broadly stated and too indiscriminately applied? Undoubtedly there are wide fields in which the law of evolution is supreme, and where it is the key to any intelligent view of the facts. But I believe there are other fields where there is no such gradual unfoldment; indeed, many classes of phenomena which remain forever unchanged; which are today as they have always been, and always will be, as long as there are phenomena at all. True religion seems to me to belong to this latter class.”

“I do not understand you,” said Montague. “The religions of man are the most varied phenomena he presents.”

“Yes,” said Johnston, “but I was speaking of true religion—religion as a fact in life—as the relation of man to the Divine. The external expressions of this in the formal religious systems of history have indeed been very diverse. But they have not evolved one into the other, nor do I see any evidences of that life in external religions which would cause them to evolve from lower to higher. Rather do I think they have all been different expressions of the same spiritual facts; given to the different races of mankind by those whose genius enabled them to see those facts. Consider the religions of China, of Egypt, of Chaldea, and of India. Widely different as are their external forms, and the symbols which they use, it still requires but a very little knowledge of them to see the underlying unity they all possess, the constant reference back to the same spiritual facts.”

“This may be quite true of the world’s great religions,” said Montague, “but it certainly is not true when we consider the whole range of religious expression from primitive Fetishism to the present day.”

“As I understand Charley’s thought,” said Mitchell, “he is now viewing religion as ‘that small old Path that leads to the Eternal’—itself endless and eternal, stretching from the infinite past to the infinite future, always present and always the same. As always there have been those upon each stage of this path, there has always been in the world every shade of religious truth. But one could not say that the expressions of these evolved one into the other.”

“How about the evolution of the Jewish faith?” asked Montague.

“That was by borrowing,” said Johnston, “first from the Egyptians, then from the Chaldeans.”

“It would seem to me that the faith of any given people might well be considered to have evolved,” said Mitchell, “just as one would move from one part of a path to another. Borrowing might well be an instrument in evolution.”

“Yes,” said Johnston, “but that is different. External religions themselves do not grow purer and higher. Rather do they degenerate from their initial revelation with the lapse of time. So that the further back toward its source we go in any religion, the purer and more spiritual does it become.”

“What better example is there of this than Christianity?” said Griscom.

“Yes,” said Johnston, “it is an admirable illustration. There is first the purely spiritual teaching of Jesus—the description of the laws of spiritual life recorded from direct experience. Then there is the step down to the teaching of his disciples—purest in John and in Paul, who were in a sense independent witnesses, with first hand experience of their own in at least part of the teaching. From there on, down through the Church Fathers to the present day, we have a gradual decadence both in understanding and in expression.”

“But now there is again an upward swing of the pendulum,” said Mitchell. “Did we not agree that we were nearer now to an understanding of Christ’s teaching than ever before?”

“Yes,” said Johnston, “but that is because there is today a new revelation. Only it is manifesting now all over the world, in many individuals and in many ways, rather than in one supreme exponent. In science, in literature, in art, above all, in Christianity itself, this new spirit breathes—this new divine revelation, this new feeling of spiritual law. The very fact that we are gathered here this evening is evidence of it, and however imperfectly we sense or express it, our own hearts and minds are illumined by this new light.”

“That,” said Mitchell, “is a matter upon which Percy should have something to say. Percy, we have heard nothing from you all the evening.”

“Well, I hardly know just what to say,” said Grant. “As I listened to our friend, Monty, I was inclined to agree with each point as he made it, because each was so beautifully presented and was made to seem so logical and simple. But the end was not pleasing, was it? And it left a rather bad taste in one’s mouth. It made me think of Heine’s Hegelian looking out of the window into the night and finding no other thing to say than ‘I am God.’ That seems,—well, let us say,—inadequate, does it not, and not very appreciative of either the beauty and majesty of existence, or of that sense of proportion science claims to give us—to pick out just one point to emphasize. Is not the difficulty Monty presents to us the old one between transcendence and immanence? I think that this disappears as soon as we take a psychological rather than a metaphysical point of view, and seek for ideals in facts.”

“Hear! Hear!” exclaimed Miller.

“You know,” said Montague, “I have been immensely interested in these discussions because it is the first time in my experience that a thing, which was perfectly patent and obvious to my mind, is objected to and denied by others, in possession of the same facts as myself, and of equally trained perceptions. It is such a plain matter of fact that we do not find what we reverence in external life, but in our own ideals. It is equally evident that we crave external and objective power in the objects of our religious faith—but that this craving is not satisfied. I should like to believe in such a power in the universe, but, where is it? How can I believe in its objective existence?”

“Why, how can you help believing in it when its presence is thrust at you in every moment of life?” said Grant. “You see the evidence everywhere and in everybody. Human life, even the most degraded, is a living testimonial to it. You cannot look into the heart of any one, even those you think the most wicked and depraved, without seeing, deep within, strange gleams of light and life and force, which sparkle like the facets of a gem. It is not, perhaps, a gem of the most perfect water; we can recognize its flaws, its irregularities, its lack of polish. But still it is a jewel, and he knows little of men’s hearts who does not see it. And it is as much a force as it is a light—a force needing only to be set free—already struggling for expression, and making for the fulfillment of those ideals which are its light, and of which you speak so much.

“Whence come these? To me they are unmistakable evidences of the existence of God as a spiritual, yet objective power. The very fact that we have ideals is evidence of God, and if I remember rightly, you yourself so implied when asked, some meetings since, of the origin of your soul’s standards. Human life, however, seems to me only one evidence among many. Everywhere in nature the same lesson is taught. We only need to stop reasoning about it, stop all our metaphysical hair-splitting and look at life and nature as they are. We will indeed be dull if we cannot then see their beauty and their worth as well as their power.

“Why is it that you think these attributes belong only to your ideals? Let us remember that the universe is considerably older than we are—that before man’s mind assumed the responsibility of running the whole universe it had been in existence for some time, and that a good deal had been accomplished. This should really be considered, and for my own part, I know that it fills me not only with respect and reverence, but with a deep and abiding sense of power.

“What of this power? What is it that made life grow, and kept the stars in their appointed course? What is it that put the light of your ideals within your heart and makes them fruitful? Whence comes their power over you? Whence your aspiration? Whence, indeed, your craving that power be possessed by worth? Why it seems to me the whole of nature is an open book, in whose pages we may find endless proofs of what you seek—endless evidence of the one great central fact of God’s existence, of His power, and of His worth.”

“The great importance of what Percy has just said, is that it changes our whole attitude toward religion and religious controversy,” said Miller. “We no longer think of the essentials of religion as things we should like to have, but, possibly, for reasons of the intellect, have no right to. We no longer think of them as in the region of possible doubt. Their sphere becomes the sphere of our actual experience, which we cannot doubt. Professor Huxley, for instance, imagined that he had lost religion, but he had it all the while in the very facts of his nature.

“Our ideals are facts. Our inspirations are facts. Take, for example, a college student, loafing across the campus, hands in pockets, a cigarette hanging from nerveless lips. Yet two months later he leads a gallant fight and meets an heroic death in the war in Cuba. Where was this heroism? Where, in the first case, the ideals and moral power which supported him in the second? Or, again, take a fellow coming up the stairs to such a meeting as this; and let him be stopped by some inspector of mental luggage, some custom-house official of reason’s domain, who examines what he has with him. How easily we would all have been passed through! ‘Nothing to declare.’ Monty would doubtless have been made to pay duty on his thesis, but which of the rest of us had with him then the ideas he has since expressed? No cross section of the mind would have shown them. In this I do not mean to point to any subconscious self—but only to the bare fact of inspiration, the fact that ideals and ideas that were not in us now are.

“We find these things within us, yet they do not come from our conscious selves, they come from a source, let us call it the under-soul, and as we reverence our ideals we must reverence the source thereof. As I remember the discussion between Henry and Monty, this also gives us a resolution of their differences. For it may be said that every ideal is not only an existence, but has a real power behind it.

“There is a power that makes for the fulfillment of the ideal. By this I merely mean that in ourselves and in nature there are many tendencies in that direction, alongside of others, which, no doubt, are in a contrary direction. Moral and religious life consists in identifying ourselves with the one sort and, so far as in us lies, in vanquishing the other. For in the religious sense all the tendencies that make for the good are united into a single conception, a single principle of good.

“In ourselves these tendencies are not wholly to be identified with our own deliberate will. The doctrine of the Holy Spirit approves itself as essentially true in experience. There is a power not ourselves within ourselves, what St. Paul calls ‘the power that worketh in us.’ We can only invite its presence, assume toward it a receptive attitude, welcome it when it comes. This is essentially the attitude of prayer.

“All this may be quite conformable to psychology and physiology, but it is none the less the essential fact upon which spiritual religion rests. Whether the power that makes for the ideal, what we may call the living ideal, is literally personal, or whether personality is only a symbol for it, is a question that need not disturb the spiritual attitude in question. The gist of the matter is that, both in the world without and in the world within, there is undeniable power making for good, calling on us to unite ourselves with it, to be its instrument. No doubt this leaves weighty problems still to be solved, but it puts the fundamentals of religion beyond the shadow of doubt. This view makes experience supreme. But, meanwhile, it admits the fitness of symbolism as a means of interpreting for the spirit the facts of its life.”

William Pepperell Montague.

“I think that Miller has just expressed the attitude toward religion and the existence of God in which the clergy find themselves,” said Grant. “So often they are asked the reason for their belief and are almost puzzled what answer to make—the fact itself is so obvious. Indeed, so plain a matter of experience is it with us—experience of spiritual law—that one could almost bring against our attitude the charge that it had ceased to be religion in that it required no faith.”

“I remember a conversation some years ago with Percy,” said Miller, “in which the question arose whether we must not say that the treasures of reason and conscience that now exist must have come from a source that possessed reason and conscience; whether it was not impossible that the river could rise higher than its source. At that time I questioned the conclusion; but afterwards reflected that the prime fact was that there actually was in the process of the universe the tendency that has wrought these results and still is working them, a true fountain of good. That fact calls for our cooperation and devotion, and makes all differences on other items secondary.”

“I most heartily agree to the view Miller has so illumined for us,” said Mitchell, “and which seems to me to take us far toward a solution of our difficulties. Not only do I believe there is a power which makes for the fulfillment of the ideal, but I believe this power is the most real and vital thing in life—is, in fact, the great flow of existence, the evolutionary stream itself, or the power behind that stream, as the attraction of the earth is behind the flow of water. It seems to me that it is our ideals which cause our growth, and as we grow our ideals grow also—always beyond and above us, always lighting for us the next step on our path.

“Another thought that comes to me is this: Parallel to the evolution of religion which Monty traced, consider the evolution of man. At first we find him little better than the animals, living, as they do, in direct contact and dependence upon external nature. His struggles, his satisfactions, his pains, and his pleasures alike come to him from the physical world. His thoughts, his emotions, his hopes, and his fears alike have their origin there, and are circumscribed thereby. His existence is almost completely wrapped up in external physical nature, and there it is that he feels the reality of his God. This is the period of Fetishism or of nature worship.

“But though the power of the object of his worship is thus felt to lie in the physical world upon which he depends, the nature of his God transcends the physical, in that it possesses worth which is not physical. This worth is in a certain sense the image of man’s next step, the prototype of those virtues toward which his heart is already turning and which he is, in time, himself to embody.

“Consider now the present stage of our evolution. No longer are we in close and direct contact with the powers of external nature. Truly we depend upon them, but our dependence is remote and seldom in our consciousness. The centre and circumference of our lives have alike passed inwards from the external physical world to the inner mental and emotional world. It is there that we now depend for our existence. It is there that we labor, there that we enjoy and suffer. Indeed, the outer world is only of value to us as it affects this inner world; as it reacts upon our inner life which now is the seat of reality. Just as when man centers his life in the physical world he finds there the reality of his worship; so we, whose lives are centered in the mental world, find in that the keenest sense of the reality of that which we worship. In each case we ascribe the power of our God to that realm of life upon which we most closely depend. And in each case the worth of our worship is something which transcends our world and leads us on, as our ideals now lead us beyond the mental to the spiritual world, unlocking for us ever higher realms of life, ever deepening realities.”

New York City Hall, 1907.

“Almost you convince me,” said Montague. “And yet—why, man, think of the cruelty of life! Think of the misery and pain and death! Think of child labour and the death rate among the children, and think of those child slaves in the Southern mills.”

“There are two sides to that child labour question,” said Griscom. “We hear much of the evils of child labour, but I am not sure that the results of child idleness are not worse. It is certainly idleness and not labor that fills our children’s courts and houses of correction and produces our criminals. I was talking recently with a man, a clergyman, by the way, who had lived long in a Southern mill town and studied the question at first hand. He thought we in the North had a very distorted idea of the actual conditions. For the most part the work of the children is very light, requiring their presence only at intervals; between which times they are usually playing in the yard, and there is one man whose special duty it is to call them in when they are needed.

“But what I think must be particularly considered is the previous condition of these children. From year’s end to year’s end the greater number of them had never had enough to eat. They belonged to poor families living back in the mountains, with practically no means of support. The coming of the mills was a God-send to them. Whole families packed up and moved into the mill town, where they could now, for the first time, get employment, and where they could get food. The father and mother would both work, and the older children help. Perhaps it is hard on these children, but it is no harder, in the long run, than was their previous life. And by their work the family could save a little money—often enough to send the younger children to school and, in more than one case that I heard of, to college. I think that even in such cases as this, if we are fair, and look at things broadly as they really are, we will see the action of bettering forces, a gradual but sure improvement.”

“But you certainly cannot call the high death rate among these children a good thing,” said Montague. “I do not see that the statistics jibe with your theory. It seems to me little short of murder.”

“I asked my friend about that,” said Griscom. “He told me that he could not recall one fatal accident to any child.”

“Yet the statistics show the death rate far higher among these children than the normal,” said Montague, “far higher than among the adult workers. Surely even your optimism cannot defend such a condition as that, or see in it anything but the cruel evil it is.”

“I should imagine,” said John, “from what we have been told of the antecedents of these children, that the death rate among them would naturally be higher than among those who were better nourished. But are we warranted in this constant assumption that death is cruel? Let us for a moment postulate immortality. Is there then any necessary evil in death? We must know more of what lies either side of death before we can speak of a high death rate as an evil thing.”

⸻

Exordium: Conscientious Clergyman.

Chapter I. The Nature of the Inquiry.

Chapter II. Christianity and Nature.

Chapter III. Evolution And Ethics.

Chapter IV. Power, Worth, and Reality.

Chapter V. Pragmatism and Religion.

Chapter VI. Mysticism and Faith.

Chapter VII. The Historian’s View.

Chapter VIII.Organization and Religion.

Chapter IX. The Theosophical Movement.

Chapter X. Signs of the Times.

Chapter XI. Has the Church Failed?

Chapter XII. Silence.

⸻

CITATIONS:

“Two Leaders.” The Sun. (New York, New York) December 1, 1906.

G. Hijo. “Questions And Answers.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. IV, No. 3 (January, 1907): 275-277.

“Good And Bad Impressions.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) January 21, 1907.

James, William. The Letters of William James Vol. II. The Atlantic Monthly Press. Boston, MA. (1920.)

Cogswell, Charles N. Cogswell Photograph Collection. Cambridge Historical Commission. Cambridge, Mssachusetts. Collection ID: P014. (1883-1921)

Higgins, Shawn F. “The Benedick: An Analysis of Talks on Religion.” Dewey Studies. Vol. VI, No. 2. (2022): 16-75.