CHRISTIANITY AND NATURE.

November 21, 1906.

A month had passed since the first Talk. On November 21, 1906, everyone returned except Farrand, who elected to no longer participate in the discussions. In the intervening days Crampton’s first son, Henry Crampton Jr., was born. Montague and his family moved into their quarters at the Helicon Home Colony. Johnston concluded a lecture series at the Astoria Assembly Rooms, and was preparing for a new series of talks on “The Renascent Ireland of Today,” at Institute Hall in Brooklyn.

Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences [Brooklyn Museum], Brooklyn, New York.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

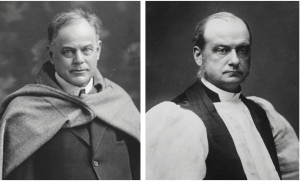

Grant attended the Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Diocese of New York on November 14, 1906. Henry Codman Potter, Bishop of the Episcopal Church in New York, stated in his address: “A minister who found himself unable to longer teach the essential doctrines of the church should retire from the priesthood.” This remark was an allusion to Algernon Crapsey, the former rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Rochester, New York, who was tried by the Episcopal Church the previous spring on charges of heresy. It would be a much-discussed topic in New York.

(Left) Algernon Crapsey. (Right.) Henry Codman Potter.

⸻

“At our last meeting,” began Mitchell, “we compared the meanings each of us attached to the word ‘religion.’ I think we all were interested to see how these supplemented each other. Religion was viewed as a going out of the emotions akin to love or the appreciation of beauty; as founded upon the search for the support and explanation of man’s sense of values; as cosmic emotion—those feelings which stir in us when we look upon the majesty of nature; as the unison of the personal will with a cosmic or divine will, the free choice of the better rather than the dearer; as a relation between God and man, expressing itself both in the climbing instinct, prayer and service, and in strength and satisfaction; as having its beginnings, or its parallel, far back of the life of man, and illustrated in such a relation as that of a dog to its master; as something more basic than any of these, lying behind them as their cause, and founded in the meaning of life itself.

“Interesting as this comparison was, and necessary as it also was for us to bring our individual views to some common focus, I think we felt as though it were but an introduction, and that we would fail of our purpose if we did not come to closer grips with the subject itself than such debate upon words and terms. I have, therefore, asked Percy to start the discussion by speaking to us of Christianity, as illustrative of what religion means to him. He has been good enough to agree to do so, though I regret I was unable to give him such time for preparation as he, perhaps, would have liked. With his presentment before us we can lay aside the philosophic method of debate and adopt the scientific procedure of inquiry instead. Here is a religion. What is its meaning to me? What does it involve? What presuppose? What imply? With this, by way of introduction and review, I will ask Percy to begin.”

“It was a kindly instinct that led Henry to speak of the short time given me for preparation,” said Grant, “But in fact there was ample opportunity to formulate my talk if I had known just what was desired. I had thought at first of writing a brief paper, but upon reflection, I found that this would grow under my hand until it became an essay and criticism upon theology, which I would not wish to inflict upon you.

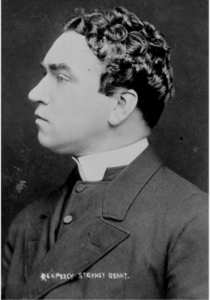

Percy Stickney Grant.

“Indeed, I doubt if any outside the clergy are aware how impossible it is to find an authoritative exposition of the principles and beliefs of the Episcopal Church. There is no single compendium of theological teaching, and if I were to attempt to give such here, I could only support my views by reference to a great variety of early-Christian writers who contributed each some one or other element in the historic development of the Church. I am sure that that is not what you would wish me to do, and, indeed, it would be equally repugnant to me, for it is just this freedom from authoritative interpretation that seems to me distinctive of Protestant Christianity; and even in the Roman Church you will find authoritative pronouncements withheld on many points, and in consequence, great diversity of opinion among its members. I am aware that upon this question of authority there are wide differences among my colleagues. Bishop Potter, for example, told us this week that every member of the clergy should have a definite theological system well grounded in the history of the Church, though, I believe, he did not extend this requirement to the laity. But I would like it clearly understood that for myself I cannot pretend to present here an authoritative teaching, but can only give you my own views—what religion means to me.

“First, then, as I look out upon life, upon this marvelous universe, with its wonderful balances and harmonies and law, I am compelled to believe in a guiding intelligence behind it and animating it. To believe the universe the result of chance, some ‘fortuitous concourse of atoms,’ seems to me, as St. George Mivart said, as absurd as to suppose that if one threw down at random the contents of a child’s box of letters they would be found arranged so as to spell a beautiful poem. Such a thing is not thinkable, and the richer and more wonderful you, gentlemen, show us nature to be, the stronger is my conviction of the intelligence supporting it. This intelligence I deem infinite—infinitely transcending my own, yet supporting and related to my own. And the logical necessity for the existence of this intelligence is the logical necessity for the existence of God.

“Next, it seems to me that the universe is not still, but in motion; in constant change and growth; that through these myriads of changing forms of life there is manifest not only intelligence, but an intelligence directed toward a definite end,—a coordinated thought and will whose end is righteousness. As the words of a spoken sentence, one by one, reveal the thought behind them, so is the end of their sequence the complete expression of that thought. Thus, as the psalmist has phrased it, ‘the heavens declare the glory of God and the firmament showeth His handiwork.’ The end of life, of that long evolutionary chain you have taught us to see, is righteousness—the fulfillment of the thought of God. There is thus a constant progress toward the spiritual.

“Again,” continued Grant, “as we look back either into human history or upon the lower forms of life we see the beginning, the germ of the present in the past. The great strides forward we have taken, the wonderful development and betterment, all had their origin in the past and were in a certain sense already present in the past. So today we have within us the germ of the future, of the progress yet to be toward a higher consciousness; toward a broader, freer, nobler life. And in a sense this is already present in us. It waits only for us to recognize it; for us to lay joyous hold upon what we can be and are to be; and to realize and express it in our thoughts and acts.

“This leads me to my view of man and of human life. I think we should view the personal man as but a scaffolding upon which we build the spiritual man. This is what St. Paul called the ‘new man,’ born from above, for we build it in the likeness of what is beyond and above us; in the likeness of our vision of God, of the ideals we sense but have not reached, of our strivings, our aspirations, and our prayers. We are building this whenever we seek unison with God, and, as I defined religion as the relation between man and God, so I would define a religious act as something done with the idea and purpose of strengthening this relation and establishing a closer unison. To go to church may or may not be a religious act, according to the motive which takes us there. To help a comrade, to sacrifice ourselves, to do good to those around us—these are equally religious acts. Indeed, any act is religious if it is done from love of good, from the desire for unison with the spirit of love and righteousness, as an expression of the relation between man and God, or with the thought of unity with God and a looking to Him. Every such act is an act of construction. There follows from it a change and a growth of moral fibre.

“It is not alone the scientist whose attitude toward life is a question. Consciously or unconsciously we are always questioning the great universal life around us and answering our questions in our acts. According to our questions are our lives, and these can be divided into two great classes—those who ask: What can life give to me? and those who ask: What can I give to life? The first is the attitude of the sensualist and the huckster. The second seems to me the attitude of the religious man. There is no bargaining in religion; no thought of gain in a gift of love. And in return life gives us ourselves; builds for us a spiritual self in which we can know it and God.

“Perhaps the most remarkable thing in the entire history of the Christian Church is the rapidity with which it departed from the teachings of Jesus and ran off the track. It is remarkable—though explicable enough when one considers the environment of the Church in the first centuries of its existence—how early Christianity was paganised; for that is precisely what happened. Jesus gathered around Him a handful of simple folk—fishermen and the like, who had neither special insight nor learning—and talked with them of the love of God and the service of others. Professor Miller put it very beautifully. Christianity is social, and the Church exists for service,—for the service of man in the spirit of Christ.

“Within two centuries this had changed. One by one the older forms of ritual, prevalent in the Jewish or ancient pagan faiths, had been engrafted upon Christianity, changed in appearance, but still recognizable. Particularly was this true with the idea of sacrifice. The gods of the Romans and the Jehovah of the Jews had alike been worshiped with sacrifices, and so deep grained had this become that Christianity could only be accepted by viewing Christ as the perpetual sacrifice. In the ritual of the mass this was taught and emphasized. Yet to me this seems foreign to the whole spirit of Christianity.

Coolidge, Baldwin. “McKim Building, Boston Public Library.” Photograph. [1906].

“I remember to have been impressed with this thought when I visited the Public Library at Boston, and saw John Singer Sargent’s mural paintings. One represents Egyptian and Assyrian nature-worships as the background for the Mosaic law, and as a preface to the prophets of Israel. The picture is full of monstrous astronomical, animal, and human symbols of fiery devotion to the instincts of the flesh, which give place to the dignified figures of Hebrew prophets, standing in a row underneath the symbolic confusion of cruder faiths. The prophets, human, isolated, rapt, represent conscience and the mind in communion with God—so ethical religion is shown emerging from sacrificial religion. At the other end of the hall, in a lunette, is Jesus the Christ. But under what guise is He depicted! He who showed that religion was Love, who placed above all the law and the prophets the love of God and the love of man, who taught us the way of service and the path of the spirit, who said of Himself that He was the way, the truth, and the life, is shown to us as dead and limp, hanging on the cross, with angels catching the blood which drips from His hands. Here is a return to sacrificial religion.

“Sargent Hall. Decorated by John Singer Sargent. Boston Public Library.”

“This sacrificial system, ingrained in Christianity, conceals and distorts its meaning. Such a representation is Byzantine Christianity and Roman Christianity, but it is not the Christianity of Galilee—not the religion of Jesus, for that was the fulfillment of the prophetic, ethical ideal. Christianity is not concerned with the dead, but the living. The essential teaching of Jesus is not that His body died to ransom us, but that His spirit lives to inspire us.

“The God of Christ’s teaching is not only the spirit of righteousness, but a Heavenly Father, to be approached freely and unafraid, requiring no mediator, no sacrifices, asking no gift but our love. For if we love God we will seek union with Him. And seeking union we will fulfill His will. I have never been able to see that Jesus taught a sacrificial system; on the contrary He opposed its idea and its effects. In many ways the liberal Christianity of today is nearer Christ than the Church has ever been before.

“I have taken more time than I had intended, and I am by no means sure that this is the sort of talk you wished to hear from me. I believe, however, that the points I have so inadequately touched upon will repay consideration.”

“You have given us, Percy, just what we wanted to focus our thought, and we are all much indebted to you,” said Mitchell. “For my own part, I would like a fuller discussion upon many of the points you have raised. Indeed, so suggestive are they that it is hard to know where to begin, unless we take them up in the order of your presentation. You commenced, if I remember rightly, by giving us certain logical arguments for the existence of a guiding intelligence behind life as we see it, whether we ascribe this intelligence to a pantheistic or a personal God, and the inevitable corollary that man is in relation to this intelligence and power for righteousness. Now I have often wondered whether any one’s religious life was in fact founded on such arguments. I confess it seems to me that these reasons are more frequently constructed to convince others than ourselves, and that it would be well to label them plainly ‘for export only.’ In saying this I am not attacking the validity of the argument, but its necessity and actual usefulness. Is it not true in your case, as I know it is in mine, that your religious feeling is founded on something far more fundamental in your nature than is argument? Does it not rest upon an interior instinct or direct perception, a simple turning of your nature, as obvious and as much a matter of fact to you as is the fact, not that an argument is true, but that you think at all? It seems to me that religious feeling is fully as fundamental as thought itself, and that to attempt to base it upon an argument is a purely artificial proceeding, indulged in only because we can not impart to others the real basis of our own certainty.”

“I am not sure that I have entirely grasped your thought,” said Grant. “I would agree that religious feeling is very fundamental, but I know my mind also seeks its intellectual justification.”

“That is a way the mind has,” Mitchell replied. “It insists upon an intellectual and logical explanation of all sorts of things—such as love and honor and unselfishness, or the appreciation of a sunset, or one’s enjoyment of music—things which it is impossible to prove have a logical explanation. And if we do not satisfy the mind it is quite likely to deny these things altogether and persuade us we do not see what we do. In consequence I think we get into the habit of concocting explanations for the mind; feeding it reasons, so as to be left in peace. But really it seems to me a pandering to a sort of mental piggishness, a vanity of intellect which is quite unwarranted. Who was the mythological personage who fed on his or her children? Whoever it was is a good image of the mind, seeking to absorb what it has no concern with and devouring instead its own thoughts.”

“As I understand you, Percy,” said Griscom, “you implied that the end of the religious life, or salvation, was a matter of unity with God, and that this end might be attained in various ways—in fact by any consistent life devoted to the love of God and service of God. Would you be willing to say that while the teaching of Jesus constituted one such way—I am sure you would say the best way—that the path taught by others might reach the same goal? That is, that Krishna and Buddha and other great religious teachers might have been looking to the same God as did Jesus, and teaching their disciples practices suited to their lives and times, which led to the same union that Jesus inculcated?”

“Yes,” Grant replied. “I see no reason why one should not think that. But I consider the Christian idea of God more active, more in accord with the vigor of the human will and with the scientific history of the universe than the Buddhist idea of God.”

“I doubt whether many Western thinkers appreciate just what the Buddhist concept is,” said Mitchell. “I know Max Müller never did.”

“I have been most interested in what you have said, Percy,” said Robinson. “Particularly in your allusion to the speed with which Christianity jumped the track, and, I would add, the completeness and the thoroughness with which it departed from its original spirit. This has been a source of constant wonder to me, as I think it is to every student of history, and this wonder deepens, as we follow the history of the Church through the Middle Ages, into the most profound admiration of the capacity of the Church fathers to misinterpret and to misrepresent. The crimes that have been committed in the name of Christianity! The aggression abroad, the extortion at home, the cruelty, torture, and murder, the magnification of pomp and splendor, the ambition for worldly power and the unswerving relentlessness of a beast of prey; what one of these was not preached and practiced in the name of Christ by the Church which claimed to follow Him! You speak of the paganization of the Christian ceremony, but what can we say of the ‘Christianizing’ of the human heart—the instilling of black fear of death, the making of a free man a cringing coward before the thought of eternal torture—torture whose meaning the Church daily showed him in life? The Church spread a pall over human life which lingers even to this day. For what other race fears death as do we?

“The more reverently we view the life and teaching of Jesus, the more we marvel at such phenomena as these. As you have said, the edifice of dogma built upon such simple foundations is sufficiently astounding, but this complete moral reversal is unequaled.”

“I do not think we should overlook the other side of the picture,” said Johnston. “If the history of the Church presents such dark blots, it is also full of very inspiring acts of heroism and nobility. The faith that produced the martyrs cannot be said to have inculcated only fear of death. Read the records of the Jesuit Missionaries in Asia, in Africa, or among the Indians in America. Moreover, even when the Church was at its worst, there never lacked those who sought to follow the example of Jesus, and who had that inner illumination which comes from living one’s beliefs. Remember that St. Francis of Assisi, for example, was leading his followers to poverty, meekness, and the Imitation of Christ, while Innocent III was magnifying the pomp and power of the Papal chair.”

“Naturally,” said Grant, “there are two sides to a religion that was officially inculcated as a transaction, but which saints discovered was a life.”

“I wonder if our biologists would not see in this an example of Mendel’s law of hybrids,” said Mitchell. “It would seem that from one point of view at least Jesus’s mission and teaching was premature. The world at large, or at least those Western people to whom His message came, had not evolved either ethically or spiritually to the point where they could assimilate such ideals. Something, however, in the manner of their presentment, or in the political and social conditions of the times, led to their adoption. The result was a genuine hybrid—a bastard product, full of hypocrisy and pretense, showing the worst features of both parents, as half-breeds seem to do. Yet, as hybrids also do, breeding progeny, pure-blooded and true to each parent, as well as hybrids like itself.

“In the light of this analogy we would expect the Middle Ages to present precisely the phenomenon described. First we would have the hypocritical churchman; sensuality and ambition masked as religion. And on either side we would have reversions to the true types. On the one hand the genuine pagan, with the pagan strength and virtues, as well as the pagan vices; the worshipper of physical strength and courage; the warrior and the adventurer, fearing neither God nor man. On the other we would have the genuine Christian, such men as St. Francis of Assisi, and the long unbroken line of Christian mystics like him, whose lives were often obscure and little known, but whose aspiration and piety light the history of Christianity.

“We would also have an explanation of certain present day features. For as our ethical standards have gradually been raised we have become more and more capable of assimilating Christ’s teaching. Our Christianity is, I believe, far less of a hybrid than it was in the past centuries. Indeed, I am beginning to think, not only, as Rev. Grant said, that we are nearer now to the right view of Jesus’s meaning than ever before, but that the real Christian era may still be to come.”

“I would like to ask what warrant you have for the belief in a power in nature which makes for righteousness?” said Montague. “ Or where you see this vast improvement of which you speak?”

“Surely that must be evident,” said Grant. “Compare the condition of the world today with what it was a thousand years ago. Does one need any other argument than that simple contrast?”

“I think, Monty, you will have to grant us that we are better than we were,” said Robinson. “The very fact that we are discussing such questions may be taken as proof of it, for consider the fate that would have been meted to us a few centuries ago. I will grant you the faults of our civilization, but every student of history must acknowledge its improvement upon the past. Indeed I think the most remarkable thing about our civilization and the thought of the world today, is the increase in the spirit of brotherliness and of unity. Personally I do not believe that Christianity is entitled to the credit for this—as one sometimes hears stated—but it is nonetheless noteworthy.”

“I quite agree with you, Robinson,” said Johnston. “Our postal and telegraph system, our railways and steamships, the constant interchange in commerce and science, and even in war, have unified the nations as they never were before, and our daily newspaper brings us the thought and happenings of the whole world. I think this is leading to something quite new in history, namely, the consciousness of humanity as a whole, or of the world thought and life as a single unit. I believe it an immense gain to have approached such a wider consciousness.”

“I must confess,” said Montague, “that you gentlemen have failed to convince me. I asked what warrant you had for believing in a power which makes for good in nature; for advocating a moral quality and uplifting element in natural process and universal law. You have all replied by speaking of the change in our civilization and the condition of man. Now it seems to me that even there there are very weak points in the argument. I might, for example, point out that as one civilization has arisen, another has declined. Simply because we ourselves have risen from barbarism in the last few thousand years, is no good reason for assuming that the whole human race has done the same. What of the civilizations of Babylon, of India, China, and Egypt? Truly our own lot may be better today than was our ancestors’ a thousand or five thousand years ago, but is the same true of the Egyptian fellaheen? And we all know that every Irishman was once a king! But, granting the improvement in man’s condition, does it not seem to you that man’s place in nature is very small, and that Nature herself, ‘red in tooth and claw,’ is far from moral, but rather cruel and relentless? Is our boasted evolution a moral evolution? Or a moral process? And even granted that the assumed greater value of the more complex organisms justified the means by which they are evolved—even granting that, is not animate nature itself lost in the great sweep of the inanimate universe? What is man’s life compared to this vast mechanism? A speck of mold upon a grain of sand. Where is the moral element in this universe of chemistry and physics and mechanics? In a cooling sun that will wipe life away as the rising tide scours the shore?”

“I am afraid I have lost the thread of your argument,” said Mitchell. “Why is it that I must find morality in natural processes?”

“Because you and Percy are basing your religious feeling upon such a faith,” said Montague. “You speak of the power which makes for good in nature and seek to unite yourselves therewith. I am questioning the existence of such a power.”

“Let us then put the matter in another way,” said Mitchell. “Whether or no law is moral, you will grant me that this is a universe of law? That throughout inanimate as well as animate nature things act and react according to one law or another?”

“Yes,” replied Montague. “Well?”

“And that the difference between things is a difference in the laws which they obey?” asked Mitchell. “The matter of this chair differs from the iron of the lamp, in that one obeys one set of laws and the other another. The one will unite with oxygen and burn in the air, the other will not. The distinction between them, and the character of each, is wholly a matter of laws which they obey. Evolution, for example, is a gradual change in the laws obeyed by the evolving type?”

“Yes,” said Montague, “but how does that touch the problem?”

“In this way,” said Mitchell. “Man, whether in a moral universe or not, is then in a universe of law. Within limits he has the definite choice of the way in which he will act and react upon his surroundings. In other words, he can himself determine the laws he will obey. And the laws he obeys determine what he is and what he becomes. He is at each moment determining his own evolution. If he chooses to obey the laws of selfishness, of lethargy, of pleasure, he becomes one thing, selfish, lethargic, and pleasure-loving. If, on the other hand, he obeys the spiritual and moral laws of aspiration and effort and unselfishness, he becomes the moral and spiritual man of which Percy spoke. In either case he unifies himself with a definite principle and law.”

“Perhaps,” said Montague, “but I do not think the identification of oneself with mere law is calculated to arouse enthusiasm as an end and object for life. No, I prefer to follow my own ideals; to recognize them as my own; small, perhaps, and very feeble set over against the might of nature, but high and noble, or, at all events, what seem good to me. This is what I wish to win and work for—the only thing for which it is worthwhile to give one’s life.”

“I do not believe we differ as much as I thought at first,” said Mitchell. “Only it seems to me you are not warranted in severing yourself from nature. You yourself are in the universe and part of it. If you think, there is thought in the world. To that extent at least the universe is thinking. If there are aspirations and ideals and morality in your heart, there is aspiration and moral law in nature. It may be great or it may be small, but it is there.”

“That is just the point,” said Montague. “The extent to which moral law is manifest in the universe is far too small to justify us in assuming that its ends are moral ends, or that it works to good. Great, big, blundering, clumsy thing that it is!”

“I entirely agree with what Monty has been saying,” said Crampton. “From a biological point of view at least, there is little ground for idealizing nature’s processes. If, for example, one takes the biological idea of ‘good,’ that is, that which tends to fulfill the two first biological laws of preservation of individual life and the preservation of the species, one sees waste and evil on all sides. One need only appeal to the familiar examples of blight and storm, earthquake and hurricane, which in sheer wanton destruction undo the long, slow work of years; or to the cruelty of this cannibalistic scheme whereby life feeds on life; or again to the process of reproduction itself. Consider, for instance, the poor little tape-worm, which has to lay three hundred million eggs that one may survive and come to fruition.”

“It may like it for all you know,” said Griscom. “For my own part I don’t see much loss.”

“That is your point of view,” said Crampton. “But how about the point of view of the two hundred and ninety-nine million, nine hundred and ninety-nine thousand, nine hundred and ninety-nine embryos which do not survive?”

“Is not survival a more or less relative term?” said Johnston “Those two hundred million odd embryos you speak of had existence of a kind, and then passed away. What more do you or I? Is it not possible to draw an analogy from humanity itself? Perhaps to some higher order of intelligence looking down upon man’s life, it may seem that only the geniuses of the human race have in any real sense lived; or, as you put it, reached fruition and survived. How many millions of men have been born to produce one genius! How rare they are! Yet how barren that civilization whose history is without them!

“We do not feel this to be an immoral arrangement. And though so few ever really live, yet all profit and share in the life of those who do. As a civilization flowers in its geniuses, so does their work contain its seed, its gift to the ages and to all mankind. The great artists and the great writers have synthesized for us an epoch and a people, have recorded them with a discernment and a breadth of view we never reached, but in which now we share.

“I think we get truer views of life when we look thus at the things we know than when we try to imagine the psychology of insects or animals.”

“I would like to ask the Crampton a question,” said John. “Both he, in his illustrations, and Monty, in alluding to a cooling sun, made the assumption that the preservation of life is the highest good. What right have you to put this ‘biological good’ in place of our ordinary moral concepts as a criterion of moral law?”

“This right—that I believe we can trace all our moral concepts as evolutionary products from biological principles,” said Crampton. “Take, for example, the second ‘great commandment’ taught by Jesus: ‘Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.’ This is a law of self-preservation for all animals that live in packs. The safety and well-being of one depends upon the well-being and strength of the whole. If the pack is diseased in health or reduced in numbers, then every individual in it is in danger. It ‘pays’ to share alike. I think all our ethical standards are derivable in the same fashion.”

“That is an extremely interesting thesis,” said Mitchell. “But has it occurred to you what an extraordinary type of ‘entire agreement’ exists between what you have been saying and the views of Monty, which you championed? While Monty maintained that morality and ideals existed only in man, you would show us that they are, in fact, biological law. Now, if I believed there was really any great difference between my views and those of Monty, I would claim that you were my ally rather than his. But for the present I fail to see why it is necessary to assume that the universe is either moral or immoral. Why is it touched by morality at all? Are not morality and immorality smaller things, applicable to a finite part, but losing their significance when extended to the infinite whole?”

“Your idea is that of ‘a splendid, unethical God’?” asked Grant.

“But is not that admission very dangerous to the whole religious point of view?” said Montague. “Is not the characteristic of the ordinary religious faith the belief that man’s ideals are universal laws? That good is permanent and will prevail? Does not your fundamental attitude require this assumption, and once departed from do you know where you will end?”

“I fear I do not,” said Mitchell. “But whether dangerous or no, this is the way it looks for the moment, and we will see where it leads us by following it, even if we do so with misgivings. Let me elaborate my thought for a moment. What is the origin of our ethical feeling? You speak of it as an ideal held within our own hearts, and to which nature is more or less antagonistic. Crampton says the same, yet finds the origin of that ideal in natural biological law. Now it seems to me that an act of ours is moral or immoral according as it is or is not in accordance with our evolution. The picture of the next step, as it were, in that evolution is held in our hearts as an ideal, as our ethical and moral standard. Equally true is it that this next step is in the same general direction as the previous ones, as our evolution must be continuous, so it is natural for us to find the origin of these ethical standards in biological efficiency.

“The standard of ethics is thus not fixed for all types of life,” Mitchell continued, “but varies according to place in the evolutionary scale. If morality is thus an adjustment of the individual to evolution—that is, to a universal process, or the relation of the part to the whole—it seems absurd to speak of the processes themselves, or the whole itself, as either moral or immoral. Have we not now an escape from our difficulties? The religious instinct appears again as a desire for union with God, with the great moving breath of life, which plays through us and through all creatures. Because this stream of life flows through us in a given direction, we call this direction good or moral, while in reality it is only good for us at this point. It is not the constancy of the direction that is essential, but the continuity of the current.”

“I also see no reason for attributing moral responsibility to natural law,” said Robinson. “Things are as they are. Nobody thinks of questioning the morality of a proposition of geometry, nor considering that an injustice is done to 2 because 2 and 2 don’t make 5, or some other number more than 4. It takes three hundred million eggs to make a tapeworm. Well, that’s a question of fact. It is no more immoral than that it should take three eggs to make a cake. Tape-worms are more expensive than cakes, that is all, and on the whole I’m glad they are. Perhaps in time nature will be unable to afford them altogether. Nor do I see any valid ground of objection on the part of the eggs. They have had whatever kind of life a tape-worm’s egg is supposed to have. One of them goes on and becomes a tapeworm. Perhaps, from the sad picture you have drawn of its lot as a parent, it wishes that it had not!”

“My poor tape-worm!” laughed Crampton.

“Yes,” said Robinson, “I find it very difficult to grow sentimental over the fate of those eggs. Unrealized possibilities? Why, the world is full of them. Were it not, the world would end. What are you and what am I? And they are not half so sad as would be their absence. Think for a moment of there being nothing more within us, nothing that we had not worked out and fulfilled. But the whole trouble is the importation of a set of ideas into an environment where they do not belong. Drummond’s Natural Law In The Spiritual World is the sort of thing I mean; a reasoning from analogies which do not exist, and the consequent falsification of both religion and science.”

“I wonder whether if Crampton had the power he would alter the death rate in tapeworms’ eggs,” said John.

“I don’t believe I would,” said Crampton.

“Then in this particular, at all events, nature’s practice does not differ from your own ethical standard?” said John. “True, you might regret the short-sightedness of the eggs, who could be assumed to view their death as a personal misfortune, but still you would realize that it was best for the world as a whole and would act as nature does. Granted this, I think your illustration fails to help your contention of nature’s immorality.”

“I spoke of nature’s waste and cruelty,” said Crampton.

“Wasteful of what?” said Mitchell. “Force never dies, nor energy, nor does matter lessen, or consciousness or feeling ever cease. The form alone changes. And from each form some new thing is gained. Cruel? It surely seems so. But in our own lives would we be without what we have gained from suffering? I suspect much of the cruelty is only apparent; an importation of our own ideas such as Robinson spoke of. My window there, for instance, looks across into a small, old, rickety, two-story building, the ground floor of which is a sweat-shop and the rooms above crowded by a washerwoman and a large family of children, swarming around her tubs and stove. Such surroundings would be misery to me, and I was at first inclined to be somewhat sentimental over their hard fate. But as I have watched them I realize that in truth they are quite satisfied with their dwelling, and would be as unhappy here as I would be there. I was reading my own sensitiveness and desire for privacy into them, who had none of it.”

“I do not think I can agree with you in such a view as that,” said Montague. “Nor can I view nature as anything but the great, blundering, senseless thing it is. It seems to me a far sounder attitude, and also a worthier one, to recognize our ideals as ours, dwelling in our own hearts. Is that not enough for a man? Do we need to bolster up our faith and support of them by attributing them also to nature? Is it not far more splendid to stand alone, if necessary, ‘thanking whatever gods may be for my unconquerable soul?’”

“‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre,’ said Grant. “It is a foolish theatrical sort of splendor. If a man finds his ideals in opposition to nature, opposed to the whole current of human life and universal law, it is time for him to get a new set of ideals. Let us play the game.”

“You, then, would only fight on the winning side?” said Montague.

“Yes—if you wish to put it so—for what can stand against God?” said Grant. “And to assume that all of God’s universe is evil because you differ from it is absurd.”

“Is not the difference between you really one of dualism versus monism,” Mitchell asked. “The Churchman finding all things work together for good, and the Socialist seeing man alone as a saving moral force in a blind universe of cruelty and waste?”

“But was not the attitude of all religious teachers essentially dualistic in the same fashion?” Montague asked. “Which one of them idealized human life as you have done tonight? It was to save men from the misery and cruelty of life, to enable them to overcome nature, that Christ taught. And what was the meaning of Buddha’s message of renunciation and the way of liberation?”

“Buddha!” exclaimed Grant. “Buddha is too mythical!”

“No more mythical than Jesus,” Montague added.

The Rivington Street Settlement, Lower East Side, Manhattan, New York. (Courtesy of the NYPL.)

“I have no patience with this false pessimistic idealism,” said Grant. “A lot of New England transcendentalists sat in their studies, or their gardens, and hatched ideals. They could think of more reforms in ten minutes than human collective effort could bring about in a century, and they condemned men for not changing everything with a bang. When later they did what they ought to have done at first, and looked out upon the great world as it is, they set up a mighty clamor because the world did not fit their theories. Why should it? Thank God, this universe is bigger and better than your brain or mine. As Ruskin said: ‘Whenever people don’t look at Nature, they always think they can improve her.’ Do you know what you ought to do? Stop living on your own thoughts, stop spinning arguments around your soul till you can neither see nor feel the great true heart of Nature. Get out of your corner and do something. Do something for your fellows. Do you know the most optimistic place in this great city? Down in the Settlement on Rivington Street. There in the slums, in contact with life and its problems—side by side with the hardship and pain and suffering—there, those who work learn to know human nature and life as it is. There pessimists become optimists.”

⸻

Exordium: Conscientious Clergyman.

Chapter I. The Nature of the Inquiry.

Chapter II. Christianity and Nature.

Chapter III. Evolution And Ethics.

Chapter IV. Power, Worth, and Reality.

Chapter V. Pragmatism and Religion.

Chapter VI. Mysticism and Faith.

Chapter VII. The Historian’s View.

Chapter VIII.Organization and Religion.

Chapter IX. The Theosophical Movement.

Chapter X. Signs of the Times.

Chapter XI. Has the Church Failed?

Chapter XII. Silence.

⸻

CITATIONS.

Drummond, Henry. Natural Law In The Spiritual World. Henry Altemus. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1892.)

“Jersey Gets The Colony.” The Sun. (New York, New York) October 3, 1906.

“Free Lectures Tonight.” The Brooklyn Times. (Brooklyn, New York) November 21, 1906.

“Many Special Lectures Planned For Brooklyn.” The Brooklyn Citizen. (Brooklyn, New York) November 25, 1906.

Coolidge, Baldwin. “McKim Building, Boston Public Library.” Photograph. [1906]. Digital Commonwealth.

Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. Talks On Religion: A Collective Inquiry. Longman, Green, and Co .New York, New York (1908): 32-61.

“Sargent Hall. Decorated by John Singer Sargent. Boston Public Library.” Photograph. [ca. 1916]. Digital Commonwealth.

New York Public Library Archives, The New York Public Library. “Rivington Street, University Settlement Building Library in 4 windows to right of doorway, second floor. Present Riv. Branch in picture, 184 Eldridge Street” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Higgins, Shawn F. “The Benedick: An Analysis of Talks on Religion.” Dewey Studies. Vol. VI, No. 2. (2022): 16-75.