“NOW, AND FOREVER.”

ACT III.

II.

⸻

“Did Bert tell you the colors I have selected for the cover of the Secret Doctrine?” asked Judge.[1]

“Dark brown and dark blue?” replied Arch.

“Right,” Judge nodded. “I cannot, with my limited help, see to all the unattended work, and so have agreed with the binder that he is to wrap up some 300 copies ready to be sent out.”

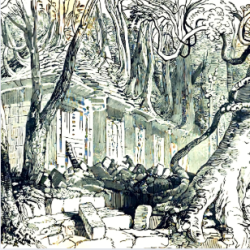

Judge was talking with Dr. Archibald “Arch” Keightley as they made their way to 16 Charlemont Mall, where the Dublin Lodge arranged to hold their public meetings.[2] They discussed, among other things, The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky’s long-awaited follow-up to Isis Unveiled, which was released shortly before Judge set sail on the Umbria. Being responsible for its publication in America, Judge had seen to the practical aspects of bringing her esoteric magnum opus to the public.

Charlemont Mall.

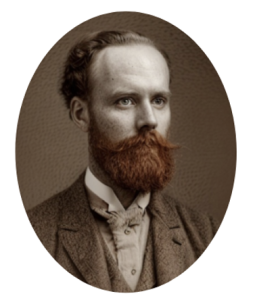

Arch was a twenty-nine-year-old doctor with a full black beard and a thoughtful face, to which spectacles added the impression of studiousness.[3] Born in Westmoreland, England, and raised in the home of Swedenborg and Quaker parents, Arch’s spiritual inclinations favored direct communication with the unseen world. In 1878, while a student at Pembroke College, Cambridge, he was among a small group who hosted a séance for the English medium, William Eglinton.[4] He then read all the books he could find on the subject of Hermeticism and Neoplatonism which led to him conducting his own Alchemical experiments. Upon graduation, Arch traveled throughout Algeria and Switzerland with his parents, Alfred and Margaret, and his ailing sister, Mary. In 1884 Arch and Bertram Keightley, his uncle four years his junior, met Blavatsky in England. They subsequently joined the Theosophical Society and became generous patrons of her work in every aspect. Her appreciation was evidenced in her inscription in Arch’s own copy of The Secret Doctrine:

To Archibald Keightley, my truly loved friend and brother, and one of the zealous editors of this work; and may these volumes, when their author is dead and gone, remind him of her, whose name in the present incarnation is—H.P. Blavatsky.[5]

When they reached their destination, Judge and Arch announced their arrival with the assistance of a heavy brass knocker.

“Two years ago, when I first heard of the Dublin Lodge, I felt it ‘ring’ in my ears,” said Judge while they waited. “Sometimes when one hears of the creation of some Lodge, or Branch as we say in America, the sound seems to fall ‘dully’ on the ears. But in the case of the Dublin Lodge, I felt that it was real. I hope it becomes a living power in Ireland. I know of no European race that was more naturally occult.”[6]

Suddenly the door opened, and a young woman opened the door.

“Mr. Judge, Dr. Keightley, please, come in!” she said warmly. “Welcome, I’m Georgie, Charley’s sister. The boys are in the parlor.”

“Thank you, Miss Johnston.”

“Please, call me Georgie.”

With Charley in Bengal, and Lewis in Ceylon, Georgie continued the work of the Dublin Branch in their absence. On November 6, 1888, Georgie, along with her neighbor, Claude Falls Wright, and their friends Alexander Weekes and Frederick Dick, entered their names in the membership roll, and went to work revitalizing the movement on the Emerald Isle.[7]

They soon entered a room where paintings of fairies and Celtic gods beautified the otherwise drab walls of the meeting place.[8] Also on the wall, printed boldly, was a quote from Blavatsky:

He who does not practice altruism; he who is not prepared to share his last morsel with a weaker or poorer than himself; he who neglects to help his brother man, of whatever race, nation, or creed, whenever and wherever he meets suffering, and who turns a deaf ear to the cry of human misery; he who hears an innocent person slandered, whether a brother Theosophist or not, and does not undertake his defense as he would undertake his own—is no Theosophist.

“Who made the paintings?” asked Judge, who was something of an artist himself.

“I did,” came the unassuming voice of George Russell.

During a mystical experience in Russell’s youth, the word “Æon” mysteriously entered his mind. He discovered later that the Gnostics had applied the word Aeon to the earliest beings of creation, so Russell adopted Æon as his own name. A confused printer, however, misread Æon as Æ, so Russell used the accidental appellation instead. Charley met Russell in 1887 and the two quickly became friends, bonding over “god-intoxicated,” literature.[9] William Butler Yeats, the co-founder of the Dublin Theosophical Society, was equally impressed with Russell and declared him “Another William Blake.”[10]

“Did you recently join with the others?” Judge asked.

“I am not a proclaimed Theosophist,” Russell replied. “I do not belong to the Society. For some reasons I am sorry, but for many reasons I am glad. One of the most cogent of the latter is the almost certain degeneracy of any Society or Sect formed by mortal hands.”[11] Russell admired Judge, whom he regarded as “the wisest and sweetest of any I have ever met.”[12] He continued with a self-conscious clarification. “I mean no disrespect to the founders of the Theosophical Society. They were animated by the purest motives—inspired by the noblest resolves. But being human, they cannot control the admission of members. They cannot read the heart, nor know the mind. And, consequently, the Theosophical Society is not representative of Theosophy, but only of itself—a gathering of many earnest seekers after truth, many powerful intellects, many saints, and many sinners and lovers of curiosity. If I have learned aright the lesson you have endeavored to teach, it is this. That development must be harmonious and must be unconscious. The danger which attends the desire to know is that the knowledge to be gained too often becomes the goal of our endeavors, instead of being the means by which to become perfect. And by ‘perfect’ I mean Union with the Absolute.”

George Russell.

Continuing to nod, Judge showed a rare smile.

“Willie dedicated his new book to Russell,” said Georgie, producing a copy of Yeats’ Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. On the dedication page it said: “Inscribed To My Mystical Friend G.R.”[13] Georgie then produced a folded, month-old newspaper and began to read aloud. “‘After an interesting and appreciative introduction, perhaps a little too discursive, Mr. Yeats presents us with a collection of Irish tales and legends, as varied and representative as it is conceivable for such a work to be.’”[14] Georgie sandwiched the clipping between the cover of the book and the title page. “Willie says that one of the characters in his new story is modeled off of Charley.”[15]

Claude Falls Wright, with no small hint of jealousy, listened as Georgie praised Yeats. It was a secret, but one poorly-kept, that Georgie and Claude were engaged.[16]

Claude Falls Wright.

“The age is a black one,” said Claude. “If the light of Christianity is divine, it has failed to disperse the Cimmerian darkness. Religious disputations and theological warfare, bigotry and hypocrisy, dogmatism and unholy discord have left their melancholy tokens.” Claude looked to Georgie for approval. “Nor has materialistic science succeeded better,” he continued. “Invaluable to the age as the catalog of facts presented by her votaries must be, yet the unhealthy disagreement between some of their most vital hypotheses has not failed to greatly damage the confidence reposed in them by their less learned brethren. A conflict of mind with mind, terminating in sectarian hostility, is the order of the hour, while the consequent drift of the masses to materialism and atheistic thought is leaving its impression on the times in nihilism and anarchistic reform.”[17]

Besides being a Dubliner, Judge had something in common with Claude. On July 11, 1864, Judge and his surviving siblings immigrated to America with their father. Taking root in Brooklyn, Frederick raised the children “under the spiked yoke of hard Methodism.”[18] Judge became an active member of the church and was even praised for his involvement in the Young Men’s Christian Union at the Fleet Street Methodist Episcopal Church. For all its faults, it was there where Judge met his wife, Ella.[19]

“How do you operate the Branches in America?” asked F.J. Dick.

“Each Branch forms itself into sections for the purpose of studying a certain subject, such as the Bhagavad Gita,” said Judge. “When the study is complete the sections compare notes, and produce, subsequently, a general statement of decisions upon which they could all agree. Without such a system as this, the movement cannot have solidarity. Moreover, it is the system adopted by a group of chelas under the direct supervision of the Masters.”[20]

“It has been the custom of many, both within and without the Theosophical world, to suppose that the investigation of the psychic powers in man,” said Judge, “and occult studies generally, are the chief objects of the Society. These, indeed, are important, but not by any means the most so. The first and the vital object of the Society was the establishment of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity. This had been thought to be a mere ‘Utopian’ theory; very desirable, indeed, but wholly impracticable. I have discovered—and this has been frequently asserted by the Masters—that we are really bound together by an invisible bond which cannot be severed—even by death.”

William Quan Judge.

He was not an eloquent speaker, not in the ordinary sense of the term. His style was simple. His addresses were typically void of display; he barely even gesticulated. What won his listeners over was his ability to speak naturally from the heart, giving to his words the weight of a conviction. His orations were a force of a “restrained but consuming devotion,” like “the compression of a steel spring,” and manifested in himself, their vessel, as a certain intensity.[21]

“Of every being whom we meet in the street,” continued Judge, “we perceive only the dense, or tangible part. This ‘material body’ is surrounded by other portions of the real man, of which the aura is, perhaps, the least limited in principle. This aura extends to a greater distance than we could conceive. If a developed man wishes to examine any distant object, it is by means of this subtle part of him that he would do so. Thus if we could realize that our auras are continually interpenetrating each other, it would become obvious in what manner we are really one, though focalized, as it were, in different centers. But even our very own bodies are not altogether separated. For when we approach any ordinary person we can perceive the heat, and if one is of a sensitive nature, the magnetism of his body. Simultaneous sympathetic thought-actions of different people in a room, or even at a great distance from each other, is another instance of this ‘Oneness.’ I will ask you to inquire into this—and I will reflect on the utterances of the Adepts in Light on the Path which was dictated by one of them for further examples.

“The sooner we agree that we are not separate from each other,” Judge continued, “the better it is for humanity, for that is the true basis of Universal Brotherhood. The general tendency of our thoughts must affect the arrangement of the atoms of our bodies. As this is the case within an individual, this principle applies to a society banded together for a common object. That is to say, each member is like an atom in the body. St. Paul is very clear upon this point. Hence if one member of that society should become dogmatic or indifferent, it must necessarily affect every other member. The atoms of a man are affected by his surroundings. But if a man devotes himself to the highest line of thought every atom must tend in that direction. Now, the Theosophical Society was founded in the year 1875. And in a period of fourteen years a change, for better or for worse, occurred in every individual. If a large number of Theosophists were now of the same opinions, were influenced by the same ideas, they would be capable of receiving from higher sources the truth for which they were seeking; they would be conscious of a wonderful awakening.

“The Theosophical Society, it should be remembered, was founded by the Masters, who were only men. How did they become more spiritual? Not by leaving home and friends; not by retiring into forest hermitages; but by believing in the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity. What were they doing now? Enjoying themselves, as some people thought? They are working everywhere for humanity in the correction of evil and in the dissemination of good. As Theosophists we should concentrate our mind on the feeling of Universal Brotherhood. It is indeed a palpable truth that—charity covers a multitude of sins.”

Arch spoke next.

“There is one point in the observations of Mr. Judge which I consider to be of paramount importance,” said Arch. “Next year will complete one of those periods of which an analogy, in the body of the individual, has been shown. In what way could the activity of the Society be best directed? Many seem to think that nothing is worthy of investigation but the psychic powers of man. The Universal Brotherhood is said to be a myth. But it is this point that the Masters have emphatically insisted upon, as being the essential object of the Society. I am glad to see that the Dublin Lodge has recognized the fact by placing that notable quotation upon the wall.

“An attempt of this kind has been made in every century up to the present time. It is an attempt to deal with the increasing materialization of spiritual thought. It is a revolt against dogma.

“The various centuries, it will be observed, have drawn to a close under similar circumstances. The end of the sixteenth century was marked by the Rosicrucians and Giordano Bruno. The end of the eighteenth by the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror. The true originator of that Revolution was the Comte de St. Germain. He was an Adept. The real object of that movement was quiet reform; but, owing to the unruly passions of men, this object was lost sight of, and the movement got out of hand. The moral was overcome by the physical revolution. Still it was by no means a failure, for it overturned the old regime in France, and its influence is felt throughout Europe. We have now entered upon a new order of things. Those of us who possess true altruism will have to fight the selfishness of the age.

“If we hold fast, the movement will be far-reaching. The task is not one, however, to be lightly entered upon. The Theosophical Movement is one which, affected itself by the past, is affecting a great number in the present, and will affect a much greater number in the future.”[22]

Archibald Keightley.

Georgie spoke next, delivering a homily reminiscent of the discourse found in Light on the Path:

“‘For which of you, desiring to build a tower, doth not first sit down and count the cost, whether he have wherewith to complete it?’

“You, who are about to take the vow of the neophyte, do you know to what you are pledging yourself? Have you considered well what it is you are about to undertake? The vow will be taken alone; in the privacy of your own chamber, on the shore of the ever-restless sea, or where some rapid river dashes headlong over mountain boulders, on its way to the plains.

“No eyes will gaze curiously at you as you stand before the altar; no ears will be strained to hear whether your voice is firm and unfaltering, as you renounce the world. But though there will be no white robed choir, no incense, or low chanted hymn; there have never been vows, taken by a novice when leaving the world for the shelter of the churches protecting arm, severer or more isolating, than those with which you now bind yourself. Have you thought well, what it means, to leave all and follow the Master? Do you know that you will have no longer a country? You will be what? A citizen of the world?

“No, an outlaw. True, you may live for many years in the land of your birth, amongst the people you have familiarly known: but you can no longer rejoice, as you consider the history of a race, of a country’s power—and say that is ‘my people,’ ‘my country,’ you can no longer weave laurels for the victors, in some great national contest. Look, and you will but see brother fighting against brother, men tortured and killed by their fellow-men.

“In the land of your birth, there is a struggle for power between opposing factions; what right have you to interfere? If you do, will you not be looked on with distrust; as a go-between, and a spy?

“Do you know that you will have no longer a home? Father and mother, brothers and sisters, husband or wife or children, compensate others for expatriation; but you, what will you left?

“It is true there is a promise of houses and lands, brothers and sisters, wives and children, a hundred-fold. But do you know how? and where? and when? When you are no longer one by yourself, but part of a whole, a drop in the ocean, will you not own houses and lands? as the wind owns them, free to come and go.

“You will have the weak, and poor, and downtrodden, and degraded and struggling men and women for your brothers and sisters. You will have won the right to help them in every way that you can—remembering always that those from whom you would protect them are—no matter how cruel and mistaken their conduct—your brothers and sisters too. You will have lost the right to despise any man or woman, no matter how fallen; they are still soiled with the mire from which you raised yourself. ‘Ages ago?’ Perhaps, but is your robe so perishable that you are unwilling to aid them for fear of smirching it? And yourself? You have lost yourself and have given your body to be the servant of humanity; it cannot serve two masters; see to it, then, that by no self-indulgence is its usefulness impaired.

“Work no longer for your own advancement. Beyond the needs of health, all possessions are held in trust for your brothers and sisters. It is written that ‘True renunciation consists in the fulfillment of daily duties, without hope of reward, without personal preference.’ Again, that we have ‘stepped outside,’ the struggle for existence; and must, no more, ‘resist, or resent the circumstances of life.’ It is necessary now to act with wisdom and without faltering; for hesitation or failure now means distress, and pain perhaps death, to those for whom you are working. You perchance have thought, hitherto, think you could suffer alone? Be ignorant no longer, can one not suffer, and the body remain insensible? You have gained the right—to use your strength to the uttermost, to give bread to the hungry, to wrestle with nature for secrets, in order to aid mankind in conquering sin and death; to acquire knowledge, that you may teach it to those around you; to every man, as much as he wills to understand.

“But you have no right henceforward to let personal feeling guide you; do two forms lie on the battlefield, the nearest a nameless outcast, that one further off, the man or woman you loved best? You have lost the right to pass by the stranger, even though the delay causes pain so intense as to leave you lifeless.

“Salve, no longer, wounded vanity with bitter words. Speech and thoughts belong to mankind to aid them, though never so little in attaining completeness of being: union with Truth, Harmony, and Righteousness. Face the future firmly; thoroughly realize what it will cost to destroy self. Test carefully your strength; can you depend on your courage to walk alone and unaided amidst the difficulties which surround you? The clouds hide those in front from your view, those behind need all your help, and example to urge them onward; vain indeed to look to them for strength or succor.

“Nevertheless have faith, what is sowed, that ripens at harvest time.

“The law of Karma is a perfectly just law. Aid mankind willingly; knowledge and power shall not fail you; work which ought to be done, can always be accomplished.

“Remember then that your fellow men are struggling with pain and death in the valley, enveloped in a thick, dark fog. Is it enough for you, who believe that sunlight and pure air may be had on the mountain top, to hurry alone to the summit promising ropes and guides, should you reach it? Rather take each step followed by all those whom your voice can persuade, your hand aid. Fastened together, they will steady you in dangerous paths; and should your body perish, another will be found to continue the search for life. As one who walks in advance, you must be more lightly burdened than the others, your garments, damp and heavy with poisonous mists, were far better cast in great part aside; and your sometime treasures forgotten, in order that you may give yourself wholly to your self-imposed task now and forever.”[23]

Following the addresses, the members walked about the room and talked among themselves. Judge approached Georgie, whose subtle perfume of sadness he unmistakably detected. It was the fragrance he often wore himself.

“Do you know what Brother Sattay’s final words were to me?” said Judge. “He said: ‘If I die, all I have is for Humanity. If I live. I will always work for it.’”[24]

“Charley says that our friends, if present at all, will not be present to us in any visible form in Heaven,” said Georgie. “He says, rather, they will make themselves felt as a moral influence.”[25]

“It makes very little difference whether Charley is right as to the question of meeting our friends in Heaven,” said Judge. “His belief will not alter the fact, whatever it may turn out to be.”[26]

Sensing that Georgie was less than satisfied, Judge continued. “I was a father once…I had a daughter named Alice…Alice Olive Judge. She was the same age as Ina when she was snatched away.”[27]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT III”

I. TOWER HAMLETS.

SOURCES:

[1] Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951): [Letter: William Q. Judge to Bertram Keightley. Oct. 26, 1888]

[2] “The Dublin Lodge.” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 15 (November 15, 1888): 246.

[3] “The Theosophists.” The St. Louis-Globe Democrat. (St. Louis, Missouri.) May 4, 1891.

[4] Campbell, J.W. “Spiritualism At The Universities.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XII, No. 15 (April 12, 1878):174-175.

[5] Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Obituary: Archibald Keightley.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXVIII, No. 3 (January 1931): 289-293.

[6] Judge, W.Q. “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. I, No. 3 (June 1886): 95-96.

[7] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4654. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Charles Alexander Weekes; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4655. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Georgina Audley Hay Johnston; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4656. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Claude Falls Wright; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4657. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Frederick John Dick. [11/6/1888.]

[8] MacBride, Maud Gonne. A Servant Of The Queen: Reminiscences. Victor Gollancz. London, England. (1938): 256-257.

[9] Æ. “The Sunset Of Fantasy (A Fragment Of An Unpublished Book).” The Green Book: Writings On Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. No. 8 (2016): 46–52; Boyd, Ernest A.“’A.E.’ Mystic and Economist.” The North American Review. Vol. CCII, No. 717 (August 1915): 251-261; Mulhall, Daniel. “George William Russell (A.E.) (1867-1935).” The Green Book: Writings On Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. No. 13 (2019): 43–51; Yeats, William Butler. Reveries Over Childhood And Youth. The MacMillan Company. New York, New York. (1916): 107-108.

[10] Tynan, Katherine. Twenty-Five Years. The Devin-Adair Company. New York, New York. (1913): 280-283.

[11] Æ. “Lodges Of Magic.” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 16. (December 15, 1888): 339-341.

[12] Eek, Sven; de Zirkoff, Boris (compilers.) William Quan Judge: The Theosophical Pioneer. The Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1969): 15.

[13] Yeats, William Butler. Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. Walter Scott. London, England. (1888.)

[14] “Irish Folk Lore.” The Dublin Weekly Nation. (Dublin, Ireland.) October 27, 1888.

[15] Murphy, William M. “William Butler Yeats’s ‘John Sherman’: An Irish Poet’s Declaration of Independence.” The Irish University Review. Vol. IX, No. 1 (Spring, 1979): 92–111.

[16] Guinness, Selina, “’Protestant Magic’ Reappraised: Evangelicalism, Dissent, and Theosophy.” Irish University Review. Vol. XXXIII, No. 1, (Spring-Summer, 2003): 14-27.

[17] Wright, Claude Falls. An Outline of the Principles of Modern Theosophy. The Path. New York, New York. (1894): viii.

[18] Olcott, H. S. “Old Diary Leaves: Chapter VIII. ” The Theosophist. Vol. XIV, No. 3 (November 1892): 67-75.

[19] “Fleet Street Young Men’s Christian Union.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York.) December 3, 1866; “Fleet Street Young Men’s Union.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York), November 28, 1871.

[20] 1889 T.S. Convention (America)

[21] Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIX, No. 1. (July 1931): 35-44.

[22] Æ. “A Reminiscence.” The Irish Theosophist. Vol. III, No. 5 (February 1895): 77-79.

[23] Johnston, G.A.H. “Now, And Forever.” The Theosophist. Vol. X, No. 112. (January 1889): 232-234.

[24] Keightley, Julia. “Tea Table Talk.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 9. (December 1888): 293-297.

[25] Johnston, Charles. “Shall We Know our Friends in Heaven?” The Path. Vol. II, No. 4 (July 1887): 119-121.

[26] “Authority.” The Path. Vol. II, No. 8 (November 1887): 252.

[27] Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951): [William Q. Judge to Anonymous. April 29, 1886]