I’ve often used Thanksgiving to talk about the realities of English settlement in Massachusetts Bay, particularly the English settlers’ subsequent slaughter and scattering of the region’s Native American population. For instance, our nation’s public schools rarely teach students that the English settlers sold thousands of captive Native Americans into slavery in the West Indies. Instead, we paint a rosy picture of first contact and leave it at that.

This year I want to do something slightly different, however.

While there likely was a meal of some sort, the “First Thanksgiving” is a largely fiction created in the nineteenth century, over two hundred years later, at a specific moment in our national history.

Thanksgiving is largely the product of Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor in Boston who spent decades agitating for the creation of a national Thanksgiving holiday. Hale was widowed with five children at age 34, and supported herself with her writing. She was the author of an 1827 novel with anti-slavery themes. While she perhaps wasn’t a radical, she was a believer in women’s rights and a supporter of Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation’s first woman doctor.

As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains:

The New England colonists were accustomed to regularly celebrating “Thanksgivings,” days of prayer thanking God for blessings such as military victory or the end of a drought. The U.S. Continental Congress proclaimed a national Thanksgiving upon the enactment of the Constitution, for example. Yet, after 1798, the new U.S. Congress left Thanksgiving declarations to the states; some objected to the national government’s involvement in a religious observance, Southerners were slow to adopt a New England custom, and others took offense over the day’s being used to hold partisan speeches and parades. A national Thanksgiving Day seemed more like a lightning rod for controversy than a unifying force.

In other words, while some states celebrated a day of thanksgiving, typically in the fall, others did not. Those states that did declare an annual day of thanksgiving—mostly northern states—celebrated it on different days.

Hale didn’t like this. In 1851, she wrote as follows:

There would be more significance of universal concord in our rejoicings as a people, were the day the same in all the States and Territories of our great nation. The sympathy of feeling would develop greater fervor of spirit in the thanksgivings which would rise from the altars and the hearths of twenty-three millions of the human race, who would unite in grateful remembrance of the blessings which had crowned the year, and spread a full feast for all. And, though the members of the same family might be too far separated to meet around one festive board, they would have the gratification of knowing that all were enjoying the feast.

In this excerpt, you can see a desire to create national unity at a time when the nation felt increasingly splintered. If everyone gathered to celebrate a national holiday—a day of thanksgiving—on the same day, Hale’s argument went, all Americans would be united, joined together in common meaning and ritual.

As the Encyclopedia Britannica continues:

Thanksgiving Day did not become an official holiday until Northerners dominated the federal government. While sectional tensions prevailed in the mid-19th century, the editor of the popular magazineGodey’s Lady’s Book, Sarah Josepha Hale, campaigned for a national Thanksgiving Day to promote unity. She finally won the support of President Abraham Lincoln. On October 3, 1863, during the Civil War, Lincoln proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving to be celebrated on Thursday, November 26.

Lincoln’s proclamation did not mention the Pilgrims, or a specific “First Thanksgiving.” Lincoln declared the last Thursday of November a national day of thanksgiving in part to promote unity, but it was also an assertion of New England’s cultural dominance during a time when the states in the South had abrogated their influence by leaving the Union. By the time a southerner once again entered the White House, Thanksgiving had become a national tradition. (I would be interested to know more about how long the holiday took to take off in the South, and whether it was initially seen as a Yankee imposition; regardless, the holiday, once federally declared, was not to be undone.)

At this point you may be wondering where the “First Thanksgiving” story fits into this history. If Thanksgiving as we practice it today originated with Sarah Josepha Hale and Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, why are school children taught about Pilgrims and Native Americans? Good question! For that, let’s turn to David Silverman, a history professor at George Washington University and the author of This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving.

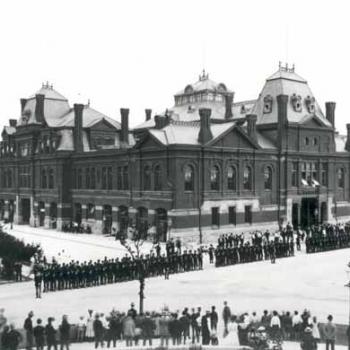

For quite a long time, English people had been celebrating Thanksgivings that didn’t involve feasting—they involved fasting and prayer and supplication to God. In 1769, a group of pilgrim descendants who lived in Plymouth felt like their cultural authority was slipping away as New England became less relevant within the colonies and the early republic, and wanted to boost tourism. So, they started to plant the seeds of this idea that the pilgrims were the fathers of America.

What really made it the story is that a publication mentioning that dinner published by the Rev. Alexander Young included a footnote that said, “This was the first Thanksgiving, the great festival of New England.” People picked up on this footnote. The idea became pretty widely accepted, and Abraham Lincoln declared it a holiday during the Civil War to foster unity.

It gained purchase in the late 19th century, when there was an enormous amount of anxiety and agitation over immigration. The white Protestant stock of the United States was widely unhappy about the influx of European Catholics and Jews, and wanted to assert its cultural authority over these newcomers. How better to do that than to create this national founding myth around the Pilgrims and the Indians inviting them to take over the land?

This mythmaking was also impacted by the racial politics of the late 19th century. The Indian Wars were coming to a close and that was an opportune time to have Indians included in a national founding myth. You couldn’t have done that when people were reading newspaper accounts on a regular basis of atrocious violence between white Americans and Native people in the West. What’s more, during Reconstruction, that Thanksgiving myth allowed New Englanders to create this idea that bloodless colonialism in their region was the origin of the country, having nothing to do with the Indian Wars and slavery. Americans could feel good about their colonial past without having to confront the really dark characteristics of it.

Having gone over all this, I have the urge to put together a U.S. history course that uses a study of the Thanksgiving holiday as its organizing principle. There is just so much here!

To restate:

Thanksgiving was declared a federal holiday in 1863 as both an attempt to create national unity during a devastating civil war, and, in some sense, as an expression of Northern cultural and political dominance (else why the opposition to creating a national holiday before the Civil War and the absence of southern politicians?).

Meanwhile, the story of the “First Thanksgiving” at Plymouth, initially promoted as part of a local tourism effort, gained support over the 19th century as a way for both New Englanders and Anglo-Saxon Protestants to assert their traditions as dominant in a fast-growing nation, diverse, multi-regional nation.

Furthermore, this story also offered Americans a way to make peace with (and paper over) their genocidal treatment of the Native Americans—a way to bring Native Americans into the American story in a way that was at once peaceful and nonthreatening, and that salved the conscience of the American public.

That’s … a lot.

In some sense, this makes Thanksgiving the quintessential American holiday.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!