Debt is a major part of economic behavior in the modern world. That hardly distinguishes modern economics from the medieval or even ancient varieties. According to Michael Hudson, debt in ancient Near Eastern societies gave rise to money rather than vice versa. (… And Forgive Them Their Debts, p. 268 et al.) That debt was what peasant farmers owed after obtaining at planting time not money but seed on credit. And that was happening as long ago as the third millennium BCE in ancient Near Eastern societies, especially Sumer and Babylon.

Paying off debts, naturally, has always been a worry. Then, as now, large numbers of people couldn’t pay their debts. A big difference between today and many of these ancient societies concerns what to do about it. Modern economies don’t deal efficiently with debt crises. Michael Hudson says we could take a lesson from the ancient world.

Debt cancellation in the ancient world

Most modern people, including most economists, exaggerate the importance of paying off debts. If debts don’t always have to be paid, we imagine a rash of people taking out irresponsible loans. Contrariwise, we imagine creditors refusing to issue loans if there is no penalty for non-payment. So for individuals who can’t pay debts we have bankruptcy “protection” (harder to get since the reform of 2005) and its negative consequences. For countries we have a mix of grants and more loans. Creditor countries or banks then impose austerity measures. That’s on a country that already can’t guarantee its citizens access to life’s necessities, including food, lodging, work, and education.

Contrast that with a not-uncommon situation in ancient Babylon or Sumer:

A Babylonian peasant farmer, working his own land, couldn’t pay his debts, due to years of unfriendly weather. His creditors demanded immediate payment or forfeiture of his land and perhaps also his wife, children and himself to debt slavery. But this farmer had a better option. “I don’t have to pay,” he said, “because the king has raised the golden torch.” (Hudson, p. 3)

That is, the king, who may have been Hammurabi, had wisely interrupted the normal economic flow. He forgave all of a huge class of debts. Essentially that was farmers’ debts but not necessarily freely chosen debts incurred in, say, starting a business.

By canceling debts this pragmatic king saved a whole class of his subjects, on whom he depended for service on public works projects like roads, temples, and irrigation canals. Or they would serve him in the military. The king much preferred a healthy, loyal, and available peasantry to a majority of subjects enslaved to a small class of wealthy elites. Far from the economic catastrophe we imagine, debt relief was an economy’s stabilizer.

From Babylon to the Bible

Catholic and other religious leaders call for forgiveness of burdensome and often unjust debts of poor countries. (See this post.) Religious warrantee for such a call they find in the Bible. But the earlier history practices of Sumer and Babylon may have been a factor. Hudson claims that the “clean slates” policies of Assyrian and Babylonian kings “inspired the debt Jubilee of Leviticus 25.” (p. 268) The people of Israel and Judah lived in the midst of, and in contact with, surrounding cultures. For 50 years in the mid sixth century BCE the elite of Judah lived in exile in Babylon. Then, if not before, Near Eastern ideas about debt and debt cancelation found their way into the writings that became the Bible.

The basic texts are from Leviticus, Chapter 25. They dictate the following provisions of the Jubilee Year, the 50th year:

- Israelites could go back to property they lost through debt foreclosure (v. 10 and 13)

- The value of land was to be the number of harvests until the next Jubilee. These harvests, not the land itself, could be bought and sold. (v. 15-16)

- The Lord was the true owner of the land. “[F]or the land is mine; with me you are but aliens and tenants.” (v. 23)

- Land that a person must sell because of unpayable debt could be “redeemed” by the person’s kin or by the person himself if he prospers later. At any rate, the purchaser may keep the land only until the next Jubilee. (v. 24-28)

- Israelites so impoverished that they must sell themselves to another, would serve as bound laborers, or slaves, but only until the year of Jubilee. Then they and their children would be free to return to their families and ancestral properties.(v. 39-42)

Other Old Testament Texts

Debt and the prospect of losing land and freedom were existential concerns for Israelite peasants and also on the minds of the ones whose writings appear in Jewish Scriptures:

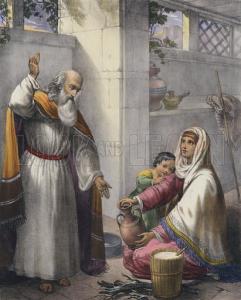

- 2 Kings 4:1-7. A creditor threatens to take a widow’s two children as slaves. Elisha multiplies the woman’s small supply of oil. She sells the oil for money to pay her debts with enough left to live on.

- Proverbs 23:10-11. “Do not remove an ancient landmark or encroach upon the field of orphans. Their redeemer is strong and he will plead their cause against you.” Mention of a “redeemer” indicates that the orphans have lost their land due to debt. (See #4 in the above list.) This land may have been transferred legally, but it is still the orphans’ ancestral property. The creditor possesses the land now, but it’s not his forever, and he must not move the ancient landmarks.

- Jeremiah 34:8-16. In the reign of King Zedekiah too many Hebrews had been reduced to debt slavery. Apparently, the tradition of setting Hebrew slaves free after six years of service had not been followed. King Zedekiah proclaimed liberty to these slaves, and the slaveholders did set them free. But later they took them back into slavery. The prophet Jeremiah condemns these unfaithful slaveholders.

- Jeremiah 39-9-10. In the process of exiling the elite of the Judeans to Babylon, the Babylonians do some of the Lord’s work. They give vineyards and fields to the poorest people, who must have lost their lands through debt. The conflict that would (and actually did) ensue in 50 years as the exiles return is easy to imagine.

- Proverbs 22:7. “The rich rule over the poor, and the borrower is slave to the lender.”

The course of Jubilee in the Bible

During the 7th century reign of King Josiah a public reading of a newly found Book of the Law prompted a spirit of repentance and recommitment. The people would have heard that they were to stop worshiping other gods. They also learned about the Sabbatical Year, when debts were to be forgiven and slaves freed – a sort of mini Jubilee Year. It must have sounded like an ancient, neglected law since the book’s author cast his writing as a long speech by Moses. Actually, it’s not certain that this law, versions of which were in use for millennia by surrounding kings, was in effect in Israel at any time before Josiah. Josiah proceeded to have idols and shrines to foreign gods destroyed. The text doesn’t tell us whether he was able, or even tried, to make the debt and slavery provisions stick.

The event of reading the Law in Josiah’s time required, besides the dramatic recovery of a “lost” book, a strong leader. It wasn’t supposed to be that way. Israel’s version of debt relief differs from that of other nations. In principle it was to be regularly occurring, every 50 (or seven) years, and instituted by divine fiat through Sacred Scripture. Only the ruler in those other nations could proclaim this reversion to a previous economic state. He did so as and when he saw fit. In Israelite practice, too, there appears to have been no Jubilee or Sabbatical Year except when a strong and good ruler proclaimed it.

Zedekiah, one of the last kings of Judea did issue a proclamation freeing Israelite slaves. The edict was put in place, but only temporarily. Slave owners soon took their slaves back. (See #3 in the second list above.) Zedekiah was neither a good nor a strong leader.

Debts were forgiven and slaves freed at least once in the Bible.

The Bible does record, in the Book of Nehemiah, one time when a Jubilee Year actually happened. This exceptional case again proves the rule that only a strong leader could institute a Jubilee.

Nehemiah had returned to Jerusalem about 100 years after the Babylonian Exile. He found a city in trouble and at the mercy of surrounding peoples. Especially dire was the decrepit condition of the city’s walls, the rebuilding of which occupied much of Nehemiah’s time. To Nehemiah’s attention, in addition, came the cry of the city’s poor:

We are having to pledge our fields, our vineyards, and our houses in order to get grain during the famine…. We are having to borrow money on our fields and vineyards to pay the king’s tax…. We are forcing our sons and daughters to be slaves…. We are powerless, and our fields and vineyards now belong to others. (Nehemiah 5:1-5)

Nehemiah gave the nobles and officials a good dressing down. He badgered these rich ones into giving up their claims on their poorer neighbors, remitting their debts, and freeing those enslaved.

I never liked another act of Nehemiah’s. In the interest of preserving religious identity, he forced all the men who had married women from the “people of the land” to send these wives and their children away. The authors of the Books of Ruth and Jonah don’t seem to have liked this policy either. (See this post and this one.) But Nehemiah redeems himself in my eyes with his concern for the poor through his remission of debt and debt slavery.

Jesus and the writer that we call Third Isaiah

Jesus in the Gospel of Luke bases his first sermon, a proclamation of Jubilee, on a text from a scroll of the prophet Isaiah.

Isaiah 61:1-2: “The spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me. He has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives and release to the prisoners; to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor….”

The last part of the book of Isaiah, Trito or Third Isaiah, comes from the period when the exiles have returned to Judea. Again the people have not been following the prescription of Leviticus about the Jubilee Year, the “year of the Lord’s favor.” Otherwise why would it have taken a prophet with a special mission from God to announce it?

The same was certainly true at the time Jesus appeared on the scene. We know, in fact, about a shady maneuver in the century before Jesus that essentially nullified the Jubilee Year. The famous rabbi Hillel, St. Paul’s teacher, feared that economic activity would be greatly harmed if creditors had to forgive loans on a regular basis. He approved a procedure, called in Hebrew prosbul, in which a court, rather than an individual, could collect a loan for the creditor even after the Jubilee Year. (See “prosbul” in the online Jewish Encyclopedia.)

Luke indicates that Jesus’ sermon got a mixed reaction, but he doesn’t tell us who was for Jesus and who against. Obviously, it was poor debtors who liked the sermon and rich creditors who objected to this upstart’s proclamation of debt forgiveness.

Jesus talks about debt

Jesus’ career might have gone down a very different path if he had had the power to enforce the Jubilee Year. He didn’t. But he didn’t stop talking about money and debt, anyway:

- Luke 6:1-13 – an unjust steward. This employee of a rich master was being fired for malfeasance. He decides to make friends among people whose debts he regularly collected. He reduces each one’s bill substantially. Possibly, he wasn’t cheating the master but only giving up his normal “take.” Jesus’ listeners would have been well-acquainted with that kind of debt collector.

- Luke 7:36–50 – two debtors and debt forgiveness. One debtor owes 500 denarii and the other 50. The creditor forgives both.

- Matthew 18:21-35 – an unforgiving creditor. This man, whose own debt, a huge sum, was forgiven, refuses to forgive a small debt owed to him.

- Mark 4:1-34 – a bountiful harvest. The harvest comes in at a ratio of 30, 60, or 100 parts to one part seed sown. Peasants hearing this story would have known what such a bumper crop meant. The farmer could now pay off his debts and even buy back land that he may have lost. (Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man, p. 177)

- Mark 4:24-25 – “Take care what you hear.” Jesus warns his followers not to believe typical folk wisdom that says, in modern equivalent, the rich always get richer and the poor poorer.

- Luke 6:35 – Lend without expecting to be repaid.

- Luke 11:4 – The Lord’s Prayer. “Forgive us our sins for we ourselves forgive everyone indebted to us.” (Luke’s version seems to be closer to Jesus’ words than the one we commonly recite.)

Money, debt, and debt forgiveness had much to do with the approaching Kingdom of God that Jesus heralded in parable and exhortation.

Jesus’ miracles and the perilous economy of the poor

In first-century Palestine, poor people, especially the day laborers about whom Jesus spoke in the Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard, were in constant economic peril. Any serious illness or disability meant unemployment and a serious threat to life itself. Jesus’ healing ministry was not just a work of charity. It was a protest against an economic system that kept poor people only a step away from losing everything. When Jesus healed on the Sabbath instead of waiting a day, he may have known that his beneficiary needed to be ready for work the very next morning.

Jesus did not have the power or authority to enforce a Jubilee Year, but his influence has grown considerably since that proclamation of Jubilee at Nazareth. At Capernaum he finds himself in a poor person’s home crowded inside and out with people enthusiastic to hear Jesus’ words. Some scribes are there also.

Friends of a paralyzed man have no other way to get him to Jesus than by lowering him through the roof. Jesus’ first move is to pronounce the man free from his sins. The scribes react with a charge of blasphemy. “Only God can forgive sins.”

But Jesus didn’t say he forgave the man’s sins; only that the sins were forgiven. That didn’t need to cause a big fuss. Unless, that is, the sins included debts that the man, unable to work, was certainly unable to pay. Contrary to what Tevye says in “Fiddler on the Roof,” it was considered a sin to be poor. Imagine how the man’s creditors felt. How will they collect on the paralytic’s debts when this crowd of Jesus enthusiasts believes the man’s debts are forgiven? As a finishing touch, Jesus cures the man’s paralysis.

Conclusion: How important is debt in the Bible?

Christians like to spiritualize the down-to-earth message of the Bible and Jesus. We say, “Money is the root of all evil.” But we’re thinking of greed, not oppressive or dysfunctional economic conditions. Jesus tells a story about a widow who has to pester a corrupt judge before he will give her a fair ruling about her inheritance. We interpret the parable as Jesus telling us to be persistent in prayer. Oh, wait. It was Luke who made that interpretation. The spiritualizing tendency goes all the way back to the writers of the New Testament Hudson says.

Jesus, no doubt, was 100 percent behind Luke as he made prayer one his Gospel’s important themes. But, like prophets before him, Jesus kept in mind the oppressive political and economic conditions under which poor people lived just as much. That comes across often in the parables that we find abundantly in Luke. There we see crushing debt, dispossession of land, and the people who have lost or are in danger of losing land in the background if not the foreground. Jesus’ stories gave the people hope.

Why did the Romans execute Jesus in a way reserved for the worst, most system-disrupting criminals? It wasn’t for teaching a theology that differed from the Jewish norm. Rome couldn’t care less about Jewish theology. But Roman rulers and the Jewish elite were living high off the labors of people at the bottom of the social hierarchy. The system worked well for them. (The same thing happens in every age, especially today.) Jesus died for our sins, but the Romans killed him because of the hope he gave people that things could be different.

Image credit: Look and Learn.