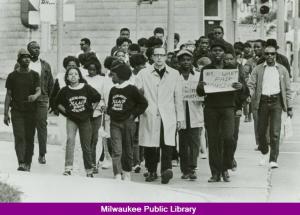

This month, February, we remember events and heroes of the civil rights movement. I’m thinking of a less well-known figure who made an impression on me when a seminarian for the Diocese of Green Bay, Wisconsin. A hundred miles to the south in Milwaukee, a priest named James Groppi was in the front of a parade of protesters, practicing non-violence. They faced angry white Milwaukeeans throwing bottles, stones, cherry bombs, bricks, and feces. Their goal: a fair-housing ordinance for the city of Milwaukee.

This is another post in the Ordinary Radicals series. Information for this post comes from these sources: Encyclopedia of Milwaukiee; University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; and Wisconsin Historical Society, and GMAR, Greater Milwaukee Association of Realtors.

Early years and radicalization

James Groppi, 1930-1985, grew up in a home attached to his family’s grocery store. His was a working-class, heavily Catholic community on south side of Milwaukee. He was the 11th of 12 children of Italian immigrants. Attending Catholic elementary and public high schools, he was captain of his school’s basketball team. He was also a bus driver, and eventually a priest for the Diocese of Milwaukee.

During Groppi’s seminary years and working summers at a youth center in Milwaukee’s inner core, he saw the suffering of blacks that discrimination caused. His first assignment as a priest showed him the prejudice among the Catholics of his southside Milwaukee parish. Impassioned preaching against racial hatred met with indifference or hostility. He asked for a transfer to the inner city.

In 1963 Groppi got his wish and began work at the predominantly black St. Boniface Parish. He participated in the 1963 March on Washington. Two years later in Selma, Alabama, he witnessed police brutality against marchers for the Voting Rights Act.

Back home later in 1965 Groppi organized protests against public school segregation. He took on leadership roles in civil rights committees. He was chaplain to the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council from 1965-68. Under Groppi’s leadership the group became famous and controversial for several civil rights initiatives. One of their first efforts assailed the local whites-only Eagles Club. Groppi led marchers to the home of a prominent Catholic jurist, who refused to give up his club membership

In 1969 Groppi organized a Welfare Mother’s March to Madison, protesting cuts in the state’s welfare budget. In 1972 he was arrested while participating in a workers’ protest and a Vietnam War protest.

Bridging the black-white divide

I became aware of Fr. Groppi’s civil rights work as he led protests against housing practices that kept blacks out of neighborhoods like the one where Groppi grew up. In 1967 riots had broken out leading to four deaths. Groppi organized a group of young blacks who named themselves the “Milwaukee Commandos,” Their purpose was to insure non-violence and to protect freedom marchers.

Milwaukee alderwoman Vel Phillips had been trying to get a fair-housing ordinance passed since 1962. She was the only black member of the City Council and the only one to vote for her fair housing. in 1965 Governor Warren Knowles signed a watered-down version of a fair-housing law for the state. It left out the overwhelming majority of Milwaukee’s housing stock. In December 1967, under pressure now, the Milwaukee City Council passed a fair-housing ordinance, but it only mirrored the weak state law. Councilwoman Phillips was the only one to vote against that law.

By this time daily fair-housing marches had begun and had attracted nationwide publicity. For 200 nights protesters marched across the 16th Street Bridge that spanned the Menominee River Valley. This half-mile wide valley separated the black inner core of the city from the southside white neighborhoods. Facing death threats, arrests, and criticism even from his own church authorities, Fr. Groppi and the marchers eventually succeeded. The city enacted the Vel Phillips Fair Housing Act in April 1968.

Toward the end of his life Fr. Groppi lived relatively obscurely. He sought and received laicization, married a member of the Catholic youth organization he had advised, raised three children, and went back to driving bus. After his death, the city of Milwaukee renamed the 16th Street Bridge. It is now the James E. Groppi Unity Bridge.

Image credit: Milwaukee Public Library