Celebrations of Grace: The Sacraments of the Catholic Church, Part 6

I have lived through a time of renewal in the Church and in her understanding of sacraments. The renewal of my own understanding of sacraments had its own timetable and path. Throughout it was the special nature of the sacramental signs that fascinated me.

The starting point for the Catholic understanding of sacramental signs is that they effect, they bring about, what they signify. When I went to church, God was going to forgive me or heal me or nourish my soul—and use some items, the sacramental signs, taken out of the created world, to make it happen. I had to understand which signs stood for which actions of God. Then I’d know what was going on. I’d know exactly what grace I would carry with me back to my daily life.

Unknowingly, I was making the sacramental signs themselves rather uninteresting. As long as some minimal conditions were met, what the signs looked like and how they were done didn’t matter much. God could have chosen any signs as long as I had a teacher or catechism to tell me what grace God was bringing through them.

Impressive ceremonies

That reasoning about sacramental signs was reinforced for me by the liturgy. The Church was always good at ceremonies. The environment and the actions with which we surrounded the presence of Jesus in the sacraments were deeply moving. Oddly, the primary sacramental signs themselves often weren’t very impressive.

As we knew them, the sacramental signs were quite small—for Baptism a small font and a few drips of water. For the Eucharist a thin wafer that didn’t look or taste like bread. The way we consumed it didn’t feel like a meal, and there was no wine except for the priest.

Other things were impressive: organ playing, singing often in Latin. As a child who understood no Latin, not even the responses we servers had to memorize, I enjoyed that challenge. Impressive also were the high altar, the crowded pews, the incense, and that moment when the Priest raised the host and chalice high so we could, finally, see them. Looking at these things, you couldn’t miss the very special work of God going on there. But we never realized that our gathering and the priest who led us were sacramental signs. We didn’t think of the Word of God as a sign either, nor did it have, except for the sermon, a very impressive place in the liturgy.

Renewal of signs

Renewal in the Church brought a new emphasis on the sacramental signs. You can see it in the place given to some of the important furnishings used in liturgy. The Baptismal font tends to be much more prominent today, and water flows more copiously. Occasionally total immersion is the sign. The ceremony takes place, preferably, during Sunday Mass in the midst of the people gathered.

The ambo, where the Word of God is proclaimed, is probably smaller than the pulpit of the former liturgy, but that’s so as not to overshadow the Word itself. God’s Word, symbolized by the book of scripture, is one very prominent feature of today’s liturgy that was almost lost before.

The Eucharistic table may be smaller than the former altar and not as fancy, but it has a more central position now. And now you can see it’s a real table. Communion is more like a meal now, especially when we partake of both bread and cup, and so it’s easier to think of Jesus as food for hungry souls than before.

The most important change in the sacramental signs is the way they are done—close to or in the midst of the people and, especially, by the people, so all can see and be involved.

New understanding

This new way of celebrating became much more meaningful to me and to many. On reflection, though, that doesn’t seem to be a good enough reason for the changes. After all, people felt personally involved in the old Mass. Everyone knew that the Eucharist was a meal and that Jesus was food for the soul. Wasn’t it enough just to know what’s happening on the distant altar and at the Communion rail and believe and do one’s best to live out the grace you received in church? What exactly is new about the new understanding of liturgy?

The new liturgy is more than just the old liturgy in a more appealing form. There’s vitality in the sacramental signs that wasn’t there before. More things are considered signs, bringing Jesus’ real presence, than before. They include gathering, presiding, and proclaiming the Word. We don’t have to look away to a distant altar for these signs; we are the signs or we do them ourselves. There’s a new understanding that says Jesus is really present in all of these signs, not just one or two.

All of that encourages a person to look for even more ways that Jesus is present. Signs are things that point, and pointers usually point outside themselves. Jesus is present and active in our world in many more ways than there are sacramental signs, and the signs point to these other ways. The sacraments symbolize and celebrate Jesus’ presence all along and all around, outside the celebration as well as in.

I used to think I was finding Christ first in the liturgy and taking that grace out into the world. Now I see that I am living with Christ first in the world, for the most part unconsciously, and symbolizing and celebrating that presence in the sacraments. That means the signs have another important job, and they have to be done well in order to pull it off. Besides carrying the presence and the grace that I first learned to find when I came to church, the signs have to be reminders of Christ’s often hidden and forgotten presence in the world. That’s new. It’s something the liturgy didn’t do, or didn’t do very well, before.

Active signs and Jesus’ work

Liturgists tell us the signs of the sacraments are more than just things, more than water, oil, bread, and wine. The signs are the actions we perform with these things, sharing the bread and the cup, pouring the water, anointing with oil.

Whoever first told me that neglected to give a reason so it was a while before I understood. But it makes good sense: What we experience in liturgy is much more than a presence. It is Christ in action, God’s saving work. God’s work is always Jesus’ work. It’s Jesus in Bethlehem, Nazareth, Galilee, Samaria, or Jerusalem. That presence of God in history is extended to us in the sacraments.

Perhaps the biggest part of God’s work is the work of Jesus that goes on anonymously in the grace flooding the whole world in every age. In the sacraments it’s as if we are plugged into the whole of Jesus’ work. That’s why the symbols are actions. It’s a very active Jesus that is present.

The people’s work

Believing in God’s presence, whether in the sacraments or in all the details of daily living, is one of the comforts Catholics enjoy. Sometimes it’s easy to forget that Jesus’ historical presence in the world led to his death on a Cross.

Years ago the phrase “Sacrifice of the Mass” was heard more commonly than it is today. But it wasn’t any easier to take the idea of sacrifice seriously then. I knew Jesus’ sacrifice on Calvary became present at every Mass, but that teaching didn’t sit well alongside the way I used to think about Jesus in Communion. This was an image of Jesus coming to me like a ship with a cargo of grace. That helped me go out and do what I needed to afterwards.

I didn’t think of Jesus as then and there drawing me into his divine, difficult, saving work, his sacrifice. But now I have to think of the Mass and all the sacraments—Communion more than any of the others—as honest-to-goodness work. The sacrament isn’t something that happens to me; it is something I do with Christ. It is not just a presence that comes but a work—that same sacrifice of Jesus. And I am part of it, along with all the assembled faithful.

This only seems new because it is so old and buried under later traditions. The Sacrifice of the Mass often now is called simply “Liturgy,” an old and revived Greek word. More obviously than before, our Mass is what that word literally means—the “work of the people.” Now when I think about the presence of Jesus in the sacraments or in the everyday world, comforting as this is, the thought of work, of sacrifice, is never far away.

Liturgy that looks like work

The first of the signs of every sacrament is the gathering of the people. A sacrament doesn’t begin after the people have gathered but with this sign of gathering. This active sign even looks like a saving work—bringing together a people who were separate.

The readings and homily that follow are just as active. We share Good News. The Bible stories and homily show that there is meaning in ordinary lives. They call forth our renewed and deepened commitments.

Then, depending on the sacrament, we go under the waters of death and resurrection or the oil of healing; we give and receive a sign of peace and forgiveness; we share a meal. It sometimes looks and feels as if God’s saving work is happening now, that same saving grace that flows from the cross and the empty tomb and from every corner of space and time.

I look around at all the faithful people worshiping together. With them I am singing songs and enacting signs that tell about everything Jesus means to do here and in the world outside, I sometimes feel strength pouring into me for work I still need to do. I know that we all are part of the strengthening, the welcoming, the forgiving, the nourishing for one another.

Think again:

Is it easier to think of the signs of the sacraments as things or as actions? Does the Mass feel like work to you? Does that work remind you of perhaps unfinished work at home or in the community?

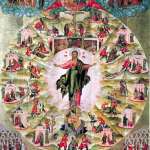

Image credit: The Eucharist Transforming a Community, via Google Images