In Luke’s Gospel Jesus “opens up” the Scriptures for two disciples on the way to Emmaus after the Resurrection. But which Scripture stories did he interpret? Perhaps the story of Achan was one. The previous post in this series mentioned that such stories might be famous or not, noble or not. This story is less than famous and much less than noble. You won’t hear Achan’s story in church; at least, it isn’t in the lectionary that Catholic and many Protestant parishes use.

Episode 1 in the series “Opening the Scriptures on the Way to Emmaus: Why Did Jesus Have to Suffer.” Introduction and a Table of Contents here.

Achan’s story has good and bad in it. The good part is the way a people who were defeated, demoralized, and at each other’s throat come together into a cohesive unit that is then able to accomplish great things. The bad part is…well, you’ll see it’s just a horrible story. But it describes very well what humans do to each other and have done from the very beginning. It’s from the Book of Joshua (Chapters 7 and 8). I’m going to tell the story with the help of James Allison, a theologian and student of René Girard. (Jesus, the Forgiving victim, Essay 3, Part 1)

The military victory

The Israelites have just come off a great victory. They had crossed the River Jordan into the Promised Land and totally demolished Jericho, the first city in their way. They put the entire population, including animals, to the sword and destroyed everything that remained, as the Lord had told them to do.

The Lord allowed an exception. Rahab, a prostitute, gave some Israelite spies good information on the condition of the city and then helped them escape. She and her family eventually joined the conquerors. Her name made it into the Gospel of Matthew as one of the ancestors of Jesus. There were some other important, but unapproved, exceptions, as became apparent later.

Right away we see why we don’t hear this story in church. Some people find a way to accept that God could order the destruction of a whole city, but I don’t know how they manage it. No good purpose justifies ethnic cleansing. (A previous post deals with such morally difficult passages in the Bible.)

Archeological evidence challenges the idea that there was a blitzkrieg through Palestine by early Israelites, as the Joshua Book relates. Even within the Bible the Book of Judges seems to tell a much more nuanced tale. Israelite society emerges gradually, experiencing both peaceful and warlike relations with neighbors. (See, for example, Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Slberman, The Bible Unearthed, pp. 72-96.)

Rivalry

You might wonder what the practical point of destroying a whole city and everything in it was. The Bible says God wanted to keep the Israelites safe from the polluting influence of false religions. If that’s the reason, then God’s plan failed. The Israelites often went ahead and worshiped other gods anyway.

Allison gives a different reason why ancient conquerors might have pursued such utter destruction. It was to prevent rivalry among the conquering horde over the conquered goods, especially the women. Rivalry turns out to be an important part of this story and of the larger story of the human race.

Disobedience and defeat

The next town in a God-directed blitzkrieg, as the story has it, is Ai. It’s much smaller, and the overconfident Israelites send up only part of their army. The people of Ai put up more resistance than expected and Israel’s army is routed. This is the defeated, demoralized, and at-each-other’s-throat part of the story.

Now God steps in and explains the cause of the problem: “The people of Israel have not obeyed my command. They have kept some of the loot of Jericho for themselves.” (Notice the plurals “people” and “they” here.) The thing to do, God continues, is to cast lots to determine who is responsible. (Notice the singular here.)

This casting of lots is a dramatic, sacred process. It takes a while because it has to go in several stages. You can’t just put a marble for every Israelite in a jar and draw them out one by one until somebody gets the red one. There are twelve tribes, so you start with twelve marbles. One is red. Imagine your relief as your tribe gets one of the blue marbles. You hear more sighs of relief as other “innocent” marbles are pulled. Until one tribe gets the guilty red one, and sighs of relief all around, except for that one tribe.

Now the process starts over as we work to identify the guilty clan within that tribe. More sighs of relief. But one clan is guilty, so we draw for the family within that clan, then the individual in that family. That single individual turns out to be Achan. Achan is made to confess his guilt. He might as well; the handwriting is on the wall.

Achan murdered and unity restored

Everybody knows that Achan isn’t the only guilty party. (The story doesn’t say that, but remember the plural in God’s original accusation.) We can easily imagine that practically every clan includes some who are guilty of hiding some very tempting loot. That circumstance that makes the sighs of relief all the more heartfelt as each person’s actual guilt is passed over.

But to accomplish the purpose of this whole sacred ceremony, only one guilty person is needed. One victim’s death atones for everyone’s sin. And you can tell that the community’s sin is forgiven. No longer is it a demoralized, at each other’s throat community, except for one throat. All rise up together and stone Achan, the unlucky, officially guilty Israelite, along with his family for good measure.

Their unity and strength restored, the Israelites resume their military campaign with amazing vigor. They demolish Ai and several more cities in rapid succession. They take undisputed possession of the land God promised them.

At the end of this story my guide, Alison, asks you to imagine this passage as a reading in church. The lector proclaims, “The word of the Lord.” And we all respond automatically, “Thanks be to God.” And then we sit there wondering, “Are we really thanking God for that!” We just don’t feel right about this story.

Jesus interpreting

Now let’s get back on the road to Emmaus with Jesus and the two disciples. Perhaps Jesus interprets this story for them. Which character does Jesus say is like himself? Could it be Joshua, the warrior leader of the Israelites in their victorious run through Palestine? Joshua and Jesus have the same name in Hebrew, but Jesus’ career doesn’t seem much like Joshua’s. The only figure in the story at all like Jesus is Achan, the officially guilty one. Achan is the victim, whose death brings peace and unity and energy back into the community.

But if Jesus identifies himself with Achan, that completely changes the story. The older scripture tells the story—like practically all of history—from the point of view of the victors. There is, however, that barely noticeable hint at the beginning of something the victors needed to forget. (Remember the plurals. There was more than one guilty one.) Jesus sees the point of view of the victim in the story. In fact, he is a victim right along with Achan.

Jesus made a lifelong choice to identify with the society’s victims—quite the opposite of the Israelites of the story. They hid from themselves their real identification with Achan. The story is no longer an account of what we have always done—find a scapegoat, someone or some group to blame. Preferably this would have been someone who is “other” and powerless, easy to dismiss. Now the story is about a new, crazy, exciting, uncomfortable idea: We all belong together, and Jesus takes a place with the ones most likely to be left out.

For that Jesus suffered. But how did his suffering help us? Did Jesus have to be the scapegoat before our story could change? The next post explains René Girard’s ideas about scapegoats.

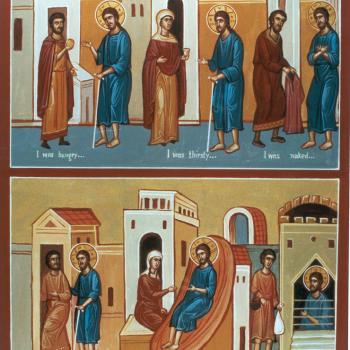

Image credit: Diana Leagh Matthews, via Google Images