Jesus enters Jerusalem knowing authorities there wanted to kill him. For about four days he skillfully avoids capture. Then, having left his disciples a memorial of himself in the form of a meal, he gives himself up. Both the first and the last parts of that puzzling behavior call for explanation. Here I suggest that the practice of civil disobedience in our day may provide a helpful analogy.

Twenty-second in a series on “The Worldly Spirituality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and a Table of Contents are HERE.

I’m going to make a historical claim which I can’t defend historically, but theologically and morally it seems to me to be necessary: Jesus did not choose to be a martyr. People who do so choose are suffering from a psychological condition called “martyr complex.” Or they may be religious fanatics, leading their followers into mass suicides. True martyrs, like St. Oscar Romero or St. Maria Goretti, do not choose martyrdom. They seek to be faithful to God or some aspect of justice or mercy and accept the fact that someone may kill them for that.

Two questions come to mind:

- What part of being faithful required Jesus to surrender to the authorities who wanted to kill him?

- What purpose did Jesus’ efforts to avoid his enemies for most of a week serve?

Jesus’ faithfulness moves him to practice civil disobedience

Jesus lived a life of faithfulness to a law higher than the Jewish and Roman legal systems. At times this required him to play fast and loose with, or simply disobey, the law of the land, to practice civil disobedience. He healed (did work) on the Sabbath, a time of complete rest. With scribes present he forgave debt when only they, not he, had authority to do so. He talked with women in public, a cultural taboo. One Sabbath he had his disciples shuck grain, or allowed them to (more work). He even engaged in petty violence in the Temple and talked about the destruction of the temple as if the temple deserved it.

Perhaps Jesus performed his greatest deed of civil disobedience during that quiet, hidden time on Thursday evening. He took a solemn Jewish observance, the Passover meal that commemorated the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt, and made it a memorial of himself. Typically the head of a family declared the meaning of the various symbols of that meal, including the unleavened bread and the wine. As head of his faith household, Jesus said about the bread and wine:

This is my body.

This is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed for many. (Mark 14:22-24)

Civil disobedience and respect for law

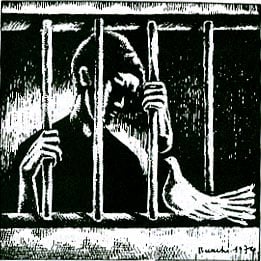

Jesus’ faithfulness to a higher law didn’t mean he wasn’t also a faithful Jew or that he didn’t accept the law’s authority. Modern heroes of protest movements give us examples of martyrs who died of violent acts outside the law. It also gives us examples of freely accepting legal punishment for conscientious civil disobedience. These are people who deliberately break unjust laws in faithfulness to a higher justice and accept the legal consequences. As Dr. King wrote in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,”

One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty. I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.

Accepting the consequences

Famously, King, Gandhi, and others practiced what they preached. Less famous but illustrative and closer to me is this story:

On Nov. 17, 2002, 86 protesters trespassed on the grounds of the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (formerly known as School of the Americas) near Columbus, Georgia. This institution has been implicated as an accessory to government-sponsored terrorism in Latin America. The protesters were promptly arrested. For this action my cousin, Sr. Caryl Hartjes, among others, served three months in Federal Women’s Prison.

Running from the law does not make a good witness. It does not convince anyone of the seriousness of the cause or one’s engagement with it. Civil disobedience must come with respect for the law or it is mere lawlessness and even dishonest. When Jesus as carried out acts of civil disobedience, I assume, he was willing to accept the legal consequence of his actions. Jesus placed principle, but not himself, above the law.

My cousin told a reporter she was scared as she crossed the line onto forbidden government property. She knew she was violating a law and faced arrest and probably jail time. It was only a shadow of what Jesus knew he faced, but then the offense of Jesus’ civil disobedience was quite a bit more serious in the eyes of the law. He attacked in words, demonstrations, and miraculous deeds the whole interlocking religions/political/economic/social system of the world that lay around the Mediterranean Sea. And Jesus was not going to run away from the consequences of his actions.

Jesus avoids the law for a while

Jesus was smart enough to know that Jewish leaders were targeting him for execution. In Jerusalem he exercised both skill and cunning in avoiding those enemies. He took advantage of his popularity with ordinary folks. When in public, it was always with a crowd, where authorities wouldn’t arrest him for fear of starting a riot. When he retired to rest it was in Bethany at the home of a leper, from which scribes and their sort would keep a safe distance.

Notice the stealth with which Jesus secured a place to celebrate Passover with his disciples: (Mark 14:12-16)

- He instructs the disciples, “A man will meet you carrying a jar of water.” A man carrying water is unusual enough to be a sign but not so unusual as to attract a lot of attention.

- Say to him, “The Teacher says, ‘Where is my guest room….’” This is a pre-arranged signal.

- The man has “a large upper room furnished and ready.” Jesus’ contact knew what was needed.

The discipleship movement has gone underground, but only temporarily. Later that Thursday evening, Jesus will go to a place where he knows he will be betrayed. Why all that clandestine work if Jesus was going to allow himself to be caught in the end? Clearly, Jesus came to Jerusalem to do something besides give himself up, and he had to stay alive long enough to get it done.

Jesus’ body at the center.

Jesus had been protesting the unjust system of his first-century Mediterranean Jewish/Roman world. But he couldn’t just protest. He couldn’t just tear down either a physical temple or an oppressive system. He had to leave something in its place. That something would be his body.

How that was going to work in Jesus’ mind is beyond my mind’s ability to ferret out. But some things are fairly certain. It involved a meal. Not many Bible scholars think that Mark, or Paul before him, made up the Last Supper. It involved taking over ancient, venerable symbols of Passover, the central Jewish story of the Exodus from Egypt. Probably Jesus thought the dangerous Jerusalem location, alongside throngs of Passover pilgrims, was necessary for that symbolism. It involved reworking the traditional interpretation of those symbols.

Interestingly and significantly, I think, Jesus didn’t mention the most important symbol of that Passover meal, the lamb. The blood of that lamb, sprinkled on the doorsteps of the Hebrews, told the destroying angel of the tenth plague to “pass over” those houses. It made the Hebrews, who were formerly no organized people, a People of God under the terms of a covenant first made with nearly forgotten ancestors. But Jesus was establishing a “new covenant” centering on his, not a lamb’s, body and blood. (Jesus is called the Lamb of God, but not in Mark’s Gospel.)

The future

A whole new people would be covered by this covenant and this blood, “shed for many.” “Many” here means the nations. Added to the Jews they are the whole world. Jesus needed to establish this new community of the Kingdom of God, which he had been preaching. But words and even miraculous deeds weren’t succeeding; they couldn’t keep a community alive in Jesus’ absence. The disciples needed a more powerful legacy, not teachings and rules but something they could touch and in touching that touch Jesus.

Could Jesus have envisioned a future complete with Catholic Mass and theologies of “real Eucharistic presence”? That’s getting too speculative for me. I think it’s safe to imagine that Jesus was linking this new Passover Supper with his previous ministry of sharing meals with no limits on who would be invited. Jesus means to go on sharing himself, especially with the poor and the ones society marginalizes.

The end?

The ending of Mark’s Gospel looks incomplete. Others tried to finish it for him. In fact, there are two very upbeat and not very literary endings tacked on to what Mark wrote. They take up verses 9 through 20 of Chapter 16 in our Bibles. They do nothing more than repeat what can be found in other Gospels and completely miss Mark’s discipleship challenge.

In Mark’s closing words the women who have gone to the tomb get instructions to carry a message to the disciples. They are to go to Galilee, where Jesus “is going before you.” (Mark 16:7) Then the women

… went out and fled from the tomb, seized with trembling and bewilderment. They said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid. (16:8)

This ending leaves readers in a kind of quandary. All they can do is try to finish the Gospel themselves. They do have instructions on how to do that. Mark, in effect, says: Go back, figuratively, to Galilee, where Jesus’ mission started. Myers says this is “a reopening of the ‘closed’ discipleship story.” (398) Follow Jesus on the way, as you did when you read or heard the story the first time. This time understand a little better the goal and meaning of the journey.

The next and last post in this series on Mark’s Gospel will consider where this mysterious non-ending puts Mark’s community and us in Jesus’ story.