John the Baptist preached repentance, but for which sins? And for whose? John and Jesus will challenge the definitions of sin that the Powers that Be preached. Third in a series on “The Worldly Spirituality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and, looking ahead, a Table of Contents are HERE.

Mark announces his intention in a title to his book, “The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” He will proclaim Jesus as Lord in battle with the forces of evil.

Immediately we see what kind of battle this is. A figure we know as John the Baptist appears in the wilderness. There he is clothed in camel hair and feeds on locusts and wild honey. This strange lifestyle, which to us might sound like a life a penance or renunciation, has political significance. John is renouncing not the world but the centers of power, whether religious or Roman, located in Jerusalem. That’s where one would expect a lord or a lordly message to appear. John the Baptist, in the wilderness, shows an unexpected preference for the margins of society and people living on the margins. And John, in operating by the River Jordan, is taking one of the most powerful symbols in the Jewish world to say to his listeners, “You are crossing over into something really new.”

Which sins, whose sins?

John’s baptism is one of repentance for forgiveness of sins. People from the whole Judean countryside were going out to him to be baptized. I try to imagine which sins all these poor people thought needed forgiving. I can’t figure it out. To me it seems that the centers of sin would have been about the same as the centers of power.

Those centers of power took it upon themselves to define sin for themselves and the rest. Though well-intended by some (especially among the Pharisees), one result was to define the poor as sinners. They had neither the time nor the means to keep all the fine points of the Law. I conclude that John the Baptist aimed his message not at crowds of individuals coming with their personal sins but at the powers and the sinful condition that misjudged the poor and kept people apart. At any rate, John the Baptist certainly challenged the centers of power. His work said God was operating somewhere else.

Mark takes the trouble to tell us what this prophetic figure is wearing—a camel hair cloak and a leather belt. It reminds us of the prophet Elijah. According to written traditions Elijah ascended into heaven in a chariot. He was supposed to reappear “before the great and terrible day of the Lord arrives.” (Malachi 4:5) Elijah had pronounced judgment on the Israel’s king Ahab and his son Azariah. Their house subsequently fell. John the Baptist, the new Elijah, pronounces judgment on Herod Agrippa. Then he tells us that one even stronger than he is coming.

The strong man

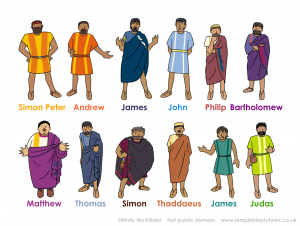

“Strong” is an important word in Mark’s Gospel, as also in the title of Myers’ book, “Binding the Strong Man.” In the first few chapters, in backwards order, we have the “strongman,” whose house you can’t enter unless you bind him up; the “strong” ones who don’t need a physician; and here Jesus, the one stronger than John the Baptist.

Oddly, the introduction of Jesus in the next scene is deliberately low-key:

It happened in those days that Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized in the Jordan by John. (1:9)

Jesus appears as one of the crowd and from Nazareth of all places, “Nowheresville,” as Myers describes it. But Galilee is famous in the South of Judea, where John baptized – famous and despised as a center both of foreign influence and rebel opposition. Mark wastes no time in attributing apocalyptic significance to the humble figure of Jesus. As he comes up out of the waters of the Jordan, Jesus sees a vision. Out of the ruptured heavens, Jesus sees “the Spirit, like a dove, descending upon him.” And a voice proclaims: “You are my beloved son; with you I am well pleased.” (1:10-11) Here Mark lets his readers in on the secret of the hero’s true identity. But he gives no indication that John the Baptist or any bystanders saw or heard anything.

A baptism of total immersion

Even apart from the heavenly show, Jesus’ baptism has a significance that the previous baptisms don’t have. John baptized the others in the Jordan, but he baptized Jesus into the Jordan. (I checked the Greek text and did indeed find that difference in prepositions that our English translations don’t catch.) The implication is that Jesus went completely under the waters and the others did not immerse themselves so. As John’s baptism is one of repentance for sin, Mark is saying that Jesus has completely freed himself from the sin of the culture, the legal/religious system, into which he was born. Jesus is now an outlaw. “The new creation begins with a renunciation of the old order,” Myers says. (129)

Then the narrative sends Jesus off into the desert and obscurity again. Out of obscurity, into the limelight, back into obscurity again. It’s a back and forth move that Myers says keeps Mark’s readers wondering about who this Jesus really is. Mark’s readers mustn’t believe Jesus will fight alongside the messianic enthusiasts gearing up for battle with Rome.

A confrontation with the true ruler of the world’s current order interrupts the obscurity of the desert. Jesus will continue the battle with Satan in the guise of the worldly powers that be that John the Baptist proclaimed.