The genealogy of Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel lists four women: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheeba. (If you count Mary there are 5, but the genealogy is on the foster father Joseph’s side. Makes no sense to me either.) It’s noteworthy that there are any women at all in the list, but Matthew’s choices are even more remarkable when you get to know these four.

The genealogy of Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel lists four women: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheeba. (If you count Mary there are 5, but the genealogy is on the foster father Joseph’s side. Makes no sense to me either.) It’s noteworthy that there are any women at all in the list, but Matthew’s choices are even more remarkable when you get to know these four.

Episode 12 of the Rowing with Michael Series:A journey through the Jewish/Christian Scriptures in Verse and Commentary. Introduction and Contents for this series HERE.

Michael, row the boat ashore. Alleluia….

- When Naomi was grieving inside, Alleluia.

- The Moabite Ruth stayed by her side. Alleluia.

- She’d lost her man, but she found another. Alleluia.

- Now she’s King David’s great-grandmother. Alleluia.

Here is a short “biography” of each of the four women that Matthew puts into his genealogy of Jesus. After that, some thoughts about why these women have their place in the New and the Old Testaments.

Tamar (Genesis 38).

Tamar was mad at Judah, one of Jacob’s 12 sons and Joseph’s older brother. Judah was supposed to give to Tamar the third and last of his sons in marriage and failed to deliver. I’m sure you can understand. Two of his sons had already married her and died. The Bible says the first son was wicked and the Lord slew him. The second son, Onan, by law had to marry her so she and her dead former husband could have legally recognized offspring. But knowing that any child they produced wouldn’t be his own, he “spilled his seed on the ground.” The Lord slew him also for the wicked behavior, i.e., for not doing his duty by Tamar.

Judah told Tamar to wait for a while until his third son grew up, but time went by and the son had grown. Judah, hoping Tamar would just forget, hadn’t acted. So Tamar dressed up like a prostitute and sat at the gate to the village where she’d heard Judah was coming. He took the bait for the price of one kid from his flock. Tamar was not dumb. She demanded, for surety until the kid would be delivered, Judah’s signet, cord, and staff. “OK,” says, Judah. “Let’s get on with it.”

Here’s what happened next, in the words of the Bible:

About three months later Judah was told, “Tamar your daughter-in-law has played the harlot; and moreover she is with child by harlotry.” And Judah said, “Bring her out, and let her be burned.” As she was being brought out, she sent word to her father-in-law, “By the man to whom these belong, I am with child.” And she said, “Mark, I pray you, whose these are, the signet and the cord and the staff.” Then Judah acknowledged them and said, “She is more righteous than I, inasmuch as I did not give her to my son Shelah.” (Genesis 38:24-26)

Tamar, now married to Shelah, gave birth to twins. One was Perez, who stood in the ancestral line of David and Jesus. Perez’ twin, Zerah, stuck his hand out first, and the midwife tied a scarlet thread on it, saying, “This came out first.” But he drew back his hand and his brother came out. It’s a curious detail. I don’t know if it’s even possible, but it makes Perez technically the second son even though he was born first. In the Bible stories God often prefers second sons. It’s one of many ways Israel’s God flouts Israel’s human traditions.

Rahab (Joshua 2).

Rahab was a prostitute by profession. It wasn’t a disguise. Her house, her place of business, was in the wall of the city of Jericho. Joshua sent spies to evaluate the enemy’s strengths and weaknesses. Guess where they went first! It makes sense. A prostitute would have a lot of information about the local militia. The king found out about the spies and sent men to Rahab to capture them. Rahab had hidden them in the straw on the roof and gave the king’s men a bum steer.

All Jericho was terrified of the Israelites, Rahab had told the spies. She was angling for a good deal for herself and her family. That was OK with the spies. They told her to hang a scarlet cord out her window (that color scarlet again), which she did. Later the victorious Israelites spared her and everybody in her house. After the destruction of Jericho, Rahab joined the Israelites and became a respectable woman. She married Salmon and became the mother of Boaz, who became the husband of Ruth.

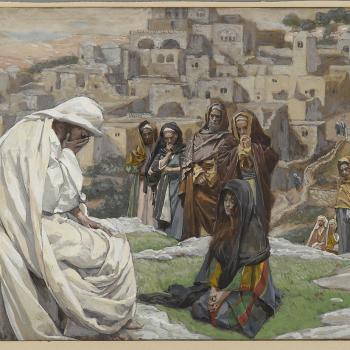

Ruth (Book of Ruth).

Noami was an Israelite living in Moab, east and a little south of Israel. Her two sons had married Moabite women. One of them was Ruth. The two sons and Naomi’s husband had all died. Naomi decided to return to Israel and encouraged the two younger women to stay and marry Moabite men. Ruth now expresses the ultimate in daughter-in-law devotion with these words:

Wherever you go I will go, wherever you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Wherever you die I will die, and there be buried. May the LORD do so and so to me, and more besides, if aught but death separates me from you! (Ruth 1:16-17)

Mother and daughter-in-law come to Bethlehem. Boaz, a near relative of Naomi, takes a fancy for Ruth, whom he finds gleaning in his fields. There follows a somewhat unseemly episode. Boaz wakes up on his threshing floor, after a hard day’s work and some drinking, to find Ruth sleeping at his “feet.” Apparently that’s a Hebraic euphemism for genitals. (Later some scribes found this disturbing enough that they changed a verb and made it Noami who lay down with Boaz. This doesn’t seem much better to me, but at least it diverted the “disgrace” away from David’s direct line.) Boaz wants to marry Ruth, regardless of who was sleeping next to him. He does so after making sure a second, closer relative to Naomi gives up his prior claim.

Ruth becomes the mother of Obed, the grandmother of Jesse, and the great-grandmother of David. Through her faithfulness to her mother-in-law Naomi, Ruth not only joins the Israelites but becomes next in line after Rahab among David’s and Jesus’ storied female ancestors.

The wife of Uriah (2 Samuel 11-12).

Matthew doesn’t name her. Her name is Bathsheba. In this story it’s the male actor, not the woman, who engages in less than seemly—in this case dastardly—behavior. Uriah was one of David’s elite soldiers so he got to live close to the royal palace—unfortunately for him. David was hanging out on his roof one day and spied Bathsheba bathing. She was very beautiful. He sent for her and had sex with her. Later she told him, “I am with child.” David tried to get Uriah to take time off from battle and spend that time with his wife. It was a good plan for hiding David’s sin. However, Uriah’s soldierly sense of honor didn’t allow him to abandon his unit in the middle of a war. Finally, David arranged to have Uriah killed in battle and took Bathsheba as one of his wives.

This story has two surprises. One is that anyone dared report and even write down such a story about Israel’s most honored king. The other is that in David’s kingdom there was at least one man, the prophet Nathan, who could call the king on the carpet and get away with it. David repented. The child died. I guess that was David’s punishment. David “comforted his wife, Bathsheba,” and she gave him another son, whom he named Solomon. Through him the ancestral line of Jesus continues.

Breaking with the status quo

What made these four women, and only these, important enough in Matthew’s mind to mention in the genealogy of Jesus? Why did earlier scribes and editors think their stories should be included in Jewish scriptures in the first place? Personally, I wouldn’t mind being a direct descendant of a beauty queen, a loyal daughter-in-law, a clever inside agent, and an assertive woman who knows how to get what’s due to her. (Actually, given the amount of time that has passed, I probably am their descendant, assuming all these people are real.) But Jews might have focused on something different: a hero king falling into depraved behavior, a member of a despised foreign race acting on one occasion like a hussy, a prostitute saving her skin, and a patriarch embarrassed by a woman pretending to be a prostitute. To say the least, these are unconventional women and uncomfortable stories.

In each case the story approves of the woman. Two stories disapprove of the men. In at least two cases the women are foreigners in a society with a strong anti-foreign bent. (Naomi had to advise Ruth not to glean in anybody else’s field except Boaz’ or she might be “insulted.”) And the Bible approves of the foreigners. There are places in the Bible where anti-foreigner sentiment reaches the point of viciousness. In the Bible women are more often put down or ignored than respected. But at other times, for a patriarchal society, the Bible is surprisingly pro-woman; and, in a society fearful of foreign contamination, it can sometimes get downright multicultural. Patriarchy and isolationism are the status quo. But the Old Testament—not always, but once in a while—breaks out of this pattern.

I believe that in these snatches of something new, something that challenges the status quo, we most clearly hear God speaking. The New Testament’s Matthew, a Jew writing for Jews in the first century listed four remarkable women in the genealogy of Jesus and kept God’s challenge going.

Image credit: Wyclif Bible Translators