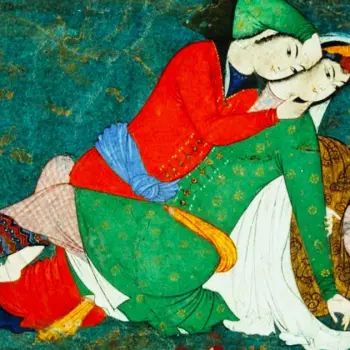

When I ask myself who or what the Beloved is in Sufi terminology, I have to admit I don’t know. Maybe the beloved is a feeling or a face, a river or a tree, a word or a silence, a presence or an absence… or That which is aware of all these things, and aware of Itself, beyond them. Nothing is more accessible than the beloved, yet He/She/It won’t be tied down. It’s baffling and pleasing, and I don’t know whether to give it a capital “B” or not when I write about it.

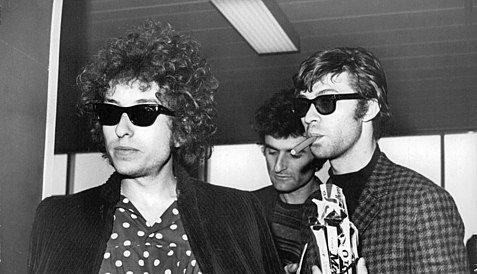

It seems to me that many of Dylan’s songs are reflections on, and reflect, this elusive beloved. Perhaps everybody’s songs do, but generally not so well. A good place to begin to describe what I mean is with Dylan’s album from 1966, Blonde on Blonde. The title cannot help but remind me of Light on Light from the Quran.[i] I’m not suggesting that Dylan was familiar enough with the Quran to make a conscious link. But these synchronicities keep coming all the same.

In 1977 he had the following exchange during an interview:

Dylan: For some reason I’ve just thought of my favorite singer.

Interviewer: Who is that?

Dylan: Om Kalsoum – the Egyptian woman who died a few years ago. She was my favorite.

Interviewer: What did you like about her?

Dylan: It was her heart.

Interviewer: Do you like dervish and Sufi singing, by the way?

Dylan: Yeah, that’s where my singing really comes from…except that I sing in America. I’ve heard too much Lead Belly really to be too much influenced by the whirling dervishes.[ii]

That’s right: he comes from the land of Woody Guthrie, Memphis Minnie, Doc Boggs, and Blind Lemon Jefferson. The whirling dervishes don’t have much do with him. And then he sings us lines like this (from “Absolutely Sweet Marie”):

Well, I got the fever down in my pockets

The Persian drunkard, he follows me

Yes, I can take him to your house but I can’t unlock it

You see, you forgot to leave me with the key

Oh, where are you tonight, sweet Marie?

A Persian “drunkard” whom Dylan might have been familiar with in 1966 was the 11th century Sufi, Omar Khayyam, whose Rubaiyat was famously translated into English by FitzGerald in 1859. Regardless, he can take a Sufi drunk on divine love to the house of Marie, but he can’t gain them admittance. But he keeps valiantly flirting with Maria as a proof of his longing: You just “forgot” – right?

For most of us, the primary association with the name Marie/Mary is likely to be the mother of Jesus, whom we might consider the purest embodiment of the Sacred Feminine. Here’s another interesting thing: scholars now believe that the linguistic root of the name Mary/Marie/Maryam is from the ancient Egyptian word for “Beloved”. And who but the Divine Beloved could claim absolute sweetness?

Significantly, many of the songs on Blonde on Blonde seem to be acknowledgments of not yet meeting the requirements of a beloved. Perhaps the most analysed song is “Visions of Johanna”. Superficially, it seems to contrast a woman, called Louise, who is available but less desirable than a woman who is absent or out of reach, called Johanna. Apart from that, it has a quality of having frozen time in a moment of intense clarity, as if the singer has suddenly become very, very present to himself and his surroundings. You could say it is a song about Awareness itself. It has baffled and mesmerised listeners for decades, but go back to the Hebrew root, and we discover that Johanna means “Grace of God”. Go back to the Germanic root of Louis/Louise and we arrive at “famous warrior” and also “long held”. Could Dylan have arrived at the awareness that he has attained worldly fame but has not attained the Beloved, the Grace of God? The adulation of the world has a stubborn hold on our egos, so that combination of “famous warrior” and “long held” might seem meaningful too.

Interestingly, some of the arresting imagery in the song starts to make sense in reference to other Sufi symbols. Dylan sings:

Oh, jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule

But these visions of Johanna, they make it all seem so cruel

For Sufis, the donkey or mule is a symbol of our ego – our animal appetites and our worldly attachments. On some level, Dylan is witnessing his (and our) idol worship. “Look,” he is saying, “at the ridiculous offerings we give to our egos!” A vision of the Grace of God makes us aware that such ego-worship is a form of self-cruelty. We weren’t created for this.

No, Bob Dylan isn’t too much influenced by the whirling dervishes, but as Rumi says, “a beautiful Love keeps on coming, skirt trailing, wine glass in hand,”[iii] and It comes through all of us to some degree, even if we’re as American as Dolly Parton.

The album finishes with “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”, written for Dylan’s wife, Sara, whom he had recently married. It is a tender portrait, but rather surprisingly it describes a woman for whom “no man comes”:

Sad-eyed lady of the lowlands

Where the sad-eyed prophet says that no man comes

My warehouse eyes, my Arabian drums

Should I leave them by your gate

Or, sad-eyed lady, should I wait?

If eyes are a window on the soul, the lady and the prophet, with their sad eyes, seem to be in some spiritual accord. The singer’s “warehouse eyes” are less certain. A warehouse might suggest material accumulation, worldly attachment and greed; on the other hand, if we imagine an empty warehouse, we may see spiritual receptivity in them. Perhaps the former is more likely however, because the prophet does not seem to count the singer as a suitor for the lady (or else the singer lacks the confidence to present himself as one). Either way, his Arabian drums seem a little foolish – he’s not sure what to do with them. They have the whiff of romance and revelation (a Muslim might even think of the drums played by the women of Medina as their beloved, the Prophet Muhammad, entered their city), but why is he not beating them to declare his love? It’s as if the singer has an inkling of what’s required, but it’s not enough. Perhaps he’s not really ready for the union, and maybe the lady isn’t either. However, one thing is clear: everybody is full of longing – the singer, the lady, the prophet – as the music and Dylan’s intonation of the lyrics roll over us like endless sand dunes.

But who, you might ask, am I suggesting is the subject of this song: Sara or some greater Beloved?… beloved on Beloved, blonde on Blonde, light on Light… could it not be both?

And what does the singer lack that would allow him to step up and become a real lover? A clue may be in the way Dylan intones “lowlands” in a long, slow descent. The moment he arrives at this word it feels like we’ve hit the very heart of the song. Perhaps what’s needed is the courage and humility to descend from our thrones into these “lowlands”. Becoming a real lover begins not so much with a stepping up as a stepping down: all spiritual paths begin with some kind of descent into the underworld of ourselves. Leonard Cohen sang: “You go to heaven once you’ve been to hell”[iv], and Rumi advises us:

Life’s waters flow from darkness.

Search the darkness, don’t run from it.[v]

But in the darkness of hell we may have to confront just how badly we’ve decorated that mule. Is it any wonder we often aren’t ready, that we’re hesitant and afraid? But the presence of the prophet in the song may be offering a key. Rumi suggests we should make friends with the prophets if we want the hazardous journey to be a success.

Of course, mystical Islam is not the only spiritual lens through which we can draw meaning from Dylan’s songs. References to the “valley” in the Tao Te Ching might be just as revealing as to the symbolic significance of the “lowlands”. Perhaps Bob Dylan isn’t much influenced by Lao Tzu either, but as Rumi says, “Love’s radiant oil never stops searching for a lamp in which to burn”[vi] and Love doesn’t much care about who influences us.

It makes sense to me that soon after Blonde on Blonde, Dylan used the excuse of a “motorcycle accident” to retire somewhat from the limelight and retreat into a country idyll with his wife and family. He’d continue to make great music, but it would sometimes baffle the expectations of his audience, as if he was trying to dismantle his former self. So much more could be said about this later music.

If Bob Dylan was not familiar with Rumi back in 1966, we know he at least has some familiarity now. The actor Mark Rylance, a big fan of both Dylan and Rumi, tells a funny story of meeting Bob Dylan backstage after a performance of the play, Jerusalem, circa 2010. In the play, Rylance plays a character called Rooster, a kind of ageing Pied Piper, an egotist, a spinner of fabulous tales, and a drug-peddler. What did Dylan see as he stared into the face of Rooster? Rylance tells us:

“I gave him a copy of Coleman Barks’s translation of the poems of Rumi, which he liked very much. But he was very nervous, and then I realised I hadn’t taken out the bashed-in prosthetic teeth I wore for the part or washed any of the blood off my face.

“He’s such an imaginative character I think he was a little bit concerned for me, because when he wanted to leave he headed off down the stairs into the basement, and I said, ‘No, Bob, that’s not going to get you out of the building – we’ve got to go up…’”[vii]

Do we?

[i] Quran 24:35

[ii] Jonathan Cott interview, Rolling Stone, 1978: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/the-rolling-stone-interview-bob-dylan-19780126

[iii] Divani Shamsi Tabrizi 2987, from Love’s Ripening, trans. Kabir Helminski and Ahmad Rezwani

[iv] “Paper-Thin Hotel” from the album Death of a Ladies’ Man, 1977

[v] The Pocket Rumi, trans. Kabir and Camille Helminski

[vi] Quatrains 353, The Rumi Daybook, trans. Kabir and Camille Helminski

[vii] Mick Brown interview, The Telegraph, 2016: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/2016/07/22/the-bfg-actor-mark-rylance-on-marlon-brando-the-oscars-meeting-h/