There are two ways to go on the Sunday before Easter. One is to celebrate Palm Sunday, which marks Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem and the adoration of the crowds who greeted him there. The other is to recognize Passion Sunday, which tells the story of Jesus’ arrest, trials, and crucifixion. Although some congregations try to harmonize these two options, or fit them into one service, they really represent two very distinct narrative moments, and liturgically speaking they are difficult to meld into one service.

For many congregations, the decision comes down to how much is going to go on during Holy Week. If there are services on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, or at other times during the week, then it might be best to emphasize the Palm Sunday texts and liturgy, and leave the passion for later in the week. On the other hand, if there are not other major services during the week, then focusing on the passion this Sunday might be necessary in order to set up Easter Sunday in the right way.

Here I will present both sets of texts–first Palm Sunday, and then Passion Sunday–so that you will have options. In so doing, it may become apparent that the division is an artificial one–an artifact of our once-a-week services and religious observance. The gospel narratives really think of the palms and the passion as one two parts of a larger whole, and they don’t divide up the story in this way. So it might be fruitful to think of connections, and not try to guard the boundaries between the two sets of texts.

Palm Sunday

What It’s About: I don’t usually include the Psalm in the week’s readings, but in this case it makes sense. Many of the Psalms are processional psalms, and while this one doesn’t quite fit that category, it is about someone making an entry into Jerusalem and into the temple to approach God.

What It’s Really About: Palm Sunday has often included a processional (with the eponymous palms and a celebratory atmosphere). This psalm sets the tone for that kind of a procession, and besides it contains other moments (the cornerstone, the gate) that provide nice points of reflection on Jesus’ procession into Jerusalem.

What It’s Not About: The journey of the psalmist is not quite matched to the journey of Jesus. The psalmist is making a somewhat personal trek, into the temple, for the purposes of thanksgiving to God. Jesus’ procession on Palm Sunday, though, looks more like a kingly procession, a reception of a ruler or another important person. There are psalms that describe that kind of procession (Psalm 95, for example), but this one is much more personal.

Maybe You Should Think About: If Lent is a journey, then this individualized psalm of journeying and arriving might well be the perfect thing to think about on the last Sunday of Lent. Can this psalm describe the path we’ve traveled in this season, and can it map out for us the place we’ve come to rest at the end of the season?

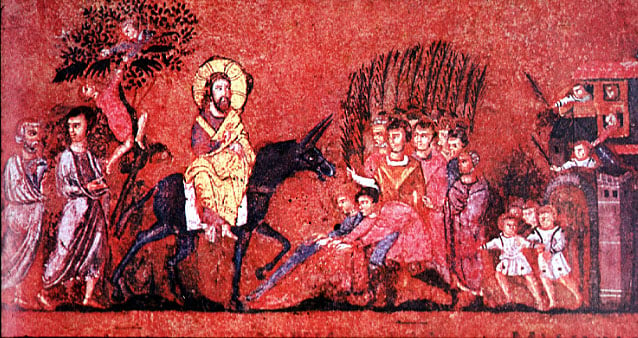

Luke 19:28-40 or John 12:12-16

What It’s About: These are two different tellings of the triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Recall that John comes from a different tradition than the synoptic gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke), and so there will usually be significant differences between John and one of other gospels. That is certainly the case here; Luke and John tell the story with different emphases and with different details. But both emphasize a kingly Jesus, and both tell of his entry into Jerusalem with shouts of acclamation.

What It’s Really About: The other day I was in a class at a church, and the group was discussing Jesus and Jesus’ attitude toward violence. Opinion was split between those who saw undercurrents of violence (sell what you have and get a sword, I come not to bring peace but a sword, etc) and those who saw Jesus as a fundamentally peaceful person. My own opinion is that whether Jesus himself advocated violence, scenes like this one bring violence into the picture whether Jesus wanted it to be there or not.

Think about this scene from the perspective of an observer at the time. Jesus is being treated like a king. He is surrounded by some of the trappings of kingship; see Zechariah 9:9 for example. He is acclaimed as a king, in both of these gospel texts, in very explicit ways. He is entering the capital city in procession. These are all things that play upon the vocabulary of power and kingship, and whether Jesus meant them in a different way, or not, is not really relevant. People saw it that way. John Dominic Crossan is fond of saying that you couldn’t look at Jesus, and hear what he was saying, and not think, “someone is going to kill this man.” This procession is exactly what Crossan means by that. You can’t go around acting like the king and having people proclaim you king, when there is a king on the throne and a Caesar at the head of the empire. Someone will kill you for that.

What It’s Not About: This isn’t Palm Sunday in Luke. Check it out–no palms. It’s cloak Sunday, maybe.

Maybe You Should Think About: Palm Sunday is a little bit confusing for me, because it seems to be such a break from what has come before. Depending on the gospel, Jesus spends a lot of time denying his importance (Mark), or insisting that it is not of this world, or teaching humility. And then he gets on the donkey and re-enacts Zechariah. Has he changed his mind? Was this the plan all along? Does he mean something different by kingship? Was he embarrassed by the whole thing? I would love to have been a fly on the wall for this procession, because I get the sense that it was more complicated than it appears in the gospels.

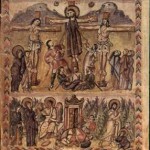

Passion Sunday

What It’s About: This is one of the texts from the Hebrew Bible to which Christians turn to understand Jesus. It is an account of someone who is beleaguered–attacked and set upon by contemporaries. He suffers physical abuse, but also rejection and marginalization. Christians see in this story a reflection of Jesus’ passion, which included both physical abuse and rejection.

What It’s Really About: This is one of the servant songs, a set of texts in Isaiah that describes someone who undergoes struggle and pain on behalf of others. The identity of the “servant” is much in dispute; some claim that it is Israel as a nation, and others that it is a particular figure, maybe even the prophet himself. But Christians have seen the servant songs as looking forward to Jesus’ life and death, and as predictions of the kind of hardships Jesus would face. It’s important to keep in mind, as Christians, that these texts were written before Jesus, and that they were undoubtedly written for another context. It’s legitimate to interpret them in light of Jesus, but that’s not how they were meant to be interpreted. It’s rather like sampling in music: lifting a tune from an older song and re-using it makes that sampled tune into something new. But the original song still stands.

What It’s Not About: The lectionary selection leaves out some surrounding material that is more vindictive and less self-sacrificing than the section we have. The surrounding material, like much of the similar material in the bible, includes curses and threats against enemies, and pleas to God to vindicate the speaker in the face of his enemies. This is still more evidence that the story of Jesus (which, in the passion at least, does not contain much vindictiveness on the part of Jesus) is being shoehorned into an older story.

Maybe You Should Think About: How does this kind of “sampling” change the song? How does Christian re-use of this Jewish text fit with, or do violence to, the meaning of the passage in its context in Isaiah? How can we preach a text like this with integrity?

What It’s About: This is one of the places Paul talks about Jesus’ death. And he does so in a way that emphasizes the self-emptying, self-sacrificial nature of it. At stake here is Jesus’ identity and status, which Paul understands that Jesus forsook and gave up in his passion and death.

What It’s Really About: This is the core of Paul’s proclamation about Jesus. Paul, when you think about it, doesn’t seem to know all that much about Jesus. He knows that Jesus instituted the last supper (1 Corinthians 11), but beyond that he doesn’t convey much about Jesus’ life or teachings. Whether that’s because he doesn’t have occasion to mention those things (he’s writing letters, after all) or because he doesn’t know about them (he’s writing in a time before the canonical gospels were written), isn’t clear. But this is the one thing Paul really hammers home about Jesus: he died in a self-sacrificial way. For Paul, this is really important, and you can see the emphasis here on the humility and obedience of Jesus. This is a major theme in Paul that is just coming back into the consciousness of biblical scholars: Jesus’ faithfulness, Jesus’ own faithfulness, is critically important to the way Paul thinks about who Jesus is.

What It’s Not About: This is an interesting text to juxtapose with the Palm Sunday texts above, because Paul is playing with language of exaltation and status. Jesus, Paul claims, was exalted, but became humble in his death. Meanwhile, the Palm Sunday texts are about the earthly exaltation of Jesus, in the same week as his passion and death. Those two together raise some interesting theological questions.

Maybe You Should Think About: This emphasis of Paul on the faithfulness of Jesus is relatively new in New Testament scholarship. It reads certain Greek phrases in ways that they haven’t been read regularly since before the Protestant Reformation, to de-emphasize our own faith (defined as assent to a proposition, or belief) and emphasize Jesus’ faith or faithfulness. This is a provocative challenge in Holy Week: how do we respond to Jesus’ faithfulness, which is evident in the gospel accounts of his passion and death?

What It’s About: The lectionary gives the option of focusing on 23:1-49, but whether you use that smaller text or the whole text as listed here, the story follows along some of the last hours of Jesus’ life. The longer text begins with the last supper, continues to the garden and arrest, and narrates the passion story up through Jesus’ death. The shorter text picks up the story with Jesus in the presence of Pilate.

What It’s Really About: Some scholars describe the gospels as “passion stories with extended introductions,” as a way of emphasizing the importance of this material in the story of Jesus. It is true that the account of Jesus’ arrest, trial, and death takes up a disproportionate amount of space; even in earliest Christianity the death of Jesus was incredibly important. Luke narrates this story with his characteristic attention to detail and observation of Roman power; he is careful to be as accurate as he knows how to the legal proceedings of the day.

Each of the gospels has a characteristic emphasis, and Luke’s is probably that Jesus is an unjustly accused man who is being put to death in a travesty of justice. (This is probably because Luke is writing for “Theophilus,” who may well be a Roman official). Luke, then, is always pointing out the ways that Jesus is innocent, and that he is being wrongly accused. At every turn, Jesus’ innocence is emphasized; even the centurion at the foot of the cross declares Jesus free of wrongdoing. Here, Jesus is the victim of religious vendettas and imperial power run amok, and his death is a miscarriage of justice.

What It’s Not About: The reading of a single gospel’s account in church is a valuable experience. It emphasizes the particularity of that gospel, and it guards us against conflating and harmonizing all four gospels in ways that do violence to them all. Luke has some very distinctive parts–the bloody sweat of 22:44 and the emphasis on Jesus looking at Peter in 22:61, for example–that bear being heard in their fullness. Resist the temptation to fill in with other gospels, or to harmonize the differences. Let Luke speak for himself.

Maybe You Should Think About: The gospel was probably heard before it was read. Reading silently, to one’s self, is a relatively modern custom. In antiquity the gospels (and other texts) would have been read aloud in the assembly of people. Reading this lengthy text aloud will take a lot of time, and it will probably even be uncomfortable for some people. But it will be worthwhile for understanding what the story might have sounded like for the earliest Christians, who heard this story in the midst of community.